Tom George

Keys to the Forest: A Poetic Journey

Illustrated by Jennie Wishart

Heartwell Books

Book review by Sandra Gibson

Tom George’s compilation of poems initially reads as an autobiographical journey, starting with childhood memories and sociological observations but the scope becomes wider and deeper, addressing social and global aspects of our current situation and contemplating geological time, the interdependence of everything and the innate wisdom of non-duality.

We have to get ourselves back to the garden, as the Hippie culture urged, and the poet offers the keys.

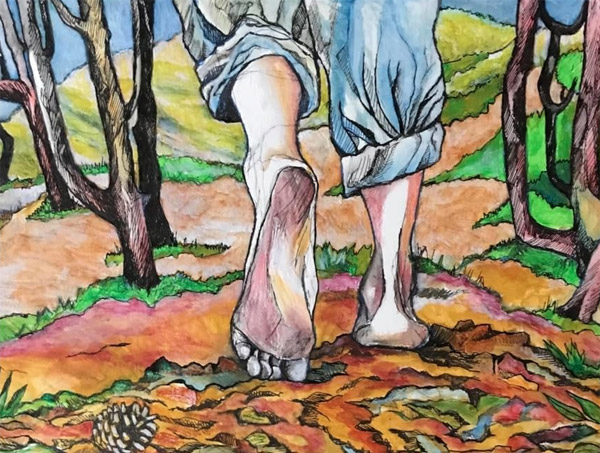

The cover illustration shows bare feet imprinted with earth: a recurring motif, and the first piece, Autumn, written as prose, introduces some of the main themes of the collection. A child is experiencing the leaves of Autumn yet already he is subject to the cautious, restraining, admonition of the adult world. Despite the pleasures of the season, there is an elegiac reflection of Autumn’s melancholy duty coming from the parents, who know from experience that such precious moments pass. In contrasting the child’s momentary frolicking with the adults’ reflectiveness, the poet has economically introduced some of the big issues: innocence and experience, being and thinking, freedom and restraint, the cycle and brevity of human life.

The theme of lost innocence re-emerges in the juxtaposed poems The Other Side of the Wall, which evokes Lennon’s epoch-marking song, lmagine, and Cold Dark Morning, which remembers his death. The former references the political idealism of the Sixties (which somehow survived appalling global events) and ends affirmatively: “Believe it we must/On the other side of the wall/The rebirth of trust”. The latter acknowledges, with the finality of the morgue, the way Lennon’s death marked the end of something more than him:

“Never has a decade slammed so cold into the face

to say an era’s gone without a trace”

The accompanying illustration is the silhouette of a street performer with head bowed in sorrow.

Yet the poems on the whole do not dwell on such desolation. The mood now swings from the drama of violent loss to the tender optimism of Sweet Charity which focuses on a sense of continuity, where each item “knows the touch of human life” and the rails of coats evoke a historical “line of dockers”. The illustration shows the multiplicity of stuff arranged with care. Library Life has a similar feeling of historical context, human interaction, and individual back stories.

The illustration of the library’s winding staircase is pivotal to the direction of the rest of the poems.

Two of the earlier poems have examined the duality that exists in human interaction. Match of the Day is literally a touching poem about childhood’s simple intimacy, and the physicality of human contact. The experiential description of sound and movement is immediate and visceral, and the father’s intuitive response is seamlessly direct. Compare this with the social distancing of polite superficial exchange described in Seen and Unseen, where “keeping friendly boundaries” is the norm, while the real person is submerged. The evenness of line length, the slowing polysyllabic words and the use of rhyme work together to support this delicate veneer of social orderliness concealing the chaotic inner landscape.

The library staircase takes the reader beyond this into a wider, deeper realm, to a different library held for millennia in rocks – the “silent spiral messenger” now held in a museum. In the poem Continuum we have human scientific scrutiny and the destructive “technocratic mission of reason and control built on burning fossils and snuffing out the soul” juxtaposed with “Gaia’s quiet power” – that eternal arena of time and ancient knowledge and natural change and powerful movement. It is at this point that the introductory quotation from Thoreau comes back into sight, revealing as it does the Romantic view of Nature’s mystery and power against the Enlightenment’s elevation of the rational, the scientific, the measurable (and the exploitable?) which manifested in the dark satanic mills and the practices of Weed World, a poem which condemns man’s dualistic domination of nature and affirms those who challenge it.

“At the same time we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be indefinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us” – Henry David Thoreau

So, the second half of Tom George’s poetry collection explores the paths of the Romantics, the seers, the solitary realisers, the transcendentalists, the shamanic visionaries, those who walk barefoot along the margins. In fact, any who would refute a solely rationalist view of reality, the objective validity of which he examines in the poem Dream upon Dream, whose illustration has a linear liquidity softly reminiscent of the lines in Munch’s famous painting of anxiety. Because infinite potential is enough to send anyone to anxiously seek the Red Man, which the poet briefly revisits in the poem The Green Man. Here, crossing the road is a metaphor for living one’s life. Humans fear danger, they fear the unknown, they fear decisions. The Red Man represents safety, rules, restraint. The Green Man is the spirit released; he also represents the Green Man of myth. The point of this poem and the one following – Permission to Live – is where the permission comes from because giving oneself permission to live spontaneously is a courageous act. Especially when everything is happening simultaneously as portrayed in At This Moment, a poem written during the Covid lockdown and illustrated by a drawing of figures, immobilised by the Rules, waving at a distant tree. There is a feeling of beautiful encroachment and an acknowledgement of the importance of Nature – today’s flowers and leaves and yesterday’s tree rings – to humans.

Nature itself – The Call of the Wild – in communion with which one develops the wisdom to “trust the instinct encoded in your bones” and “uncover the lessons you already know” is the important key. Riverman is portrayed as someone who has heeded the call and developed an “elemental quietude” from “ageless lessons that still the mind”. He has meditated and found the way and has concluded, “Words are not the place to start”, unless they honour the divinity within him. And to reflect this, the poem has short lines, sometimes only having one word. The illustration places him at the water’s edge – a place of fluidity, part of Nature.

Groundling brings us full circle from the experiential first poem Autumn, with its woodland walks, and is likewise written in prose. It has the immediacy of a first-person present tense narrative whereas the Autumn writing is third-person present tense giving it more distance than the personal I of Groundling. The poet feels the “ground under naked feet” just like River Man; just like the beachcomber in Lost and Found; just like the illustration on the book’s cover. Without shoes imprisoning his feet and muffling his sense of the Earth’s contours, he can have an “immersive reconnection”.

The journey ends – or does it begin – with the poem Inner Vision, an affirmation to live “right now and here”. There is a proclamation:

“I’ll let the drama go

I’ll let the dharma show”

Whilst acknowledging the helpfulness of the ideas, the poet resists the Buddhist label, presumably because “words are not the place to start”.

Tom George’s poetry collection has narrative logic and also reflects the current concern of respected thinkers about the imbalance that has occurred in our ways of responding to our world. The bias towards what has been called left-sphere thinking, which is logical and rational, but restraining, has been manifested in a movement towards crisis management and totalitarian solutions which deny the importance of creative thinking and the wider long-term picture. So, more power to your creativity, Tom George!