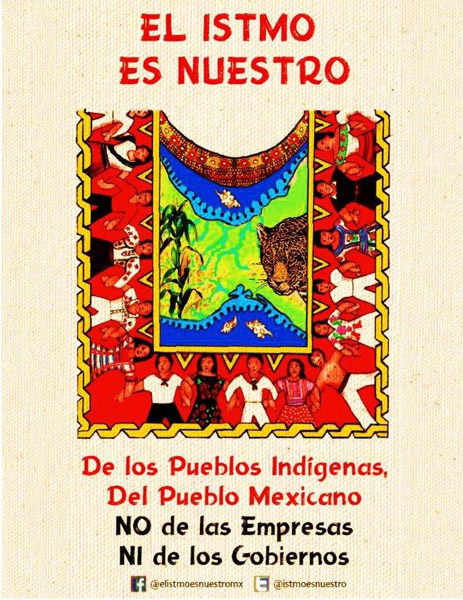

(Image above: © @elistmoesnuestromx)

Susanne Hofmann introduces the Interoceanic Corridor Project in Southern Mexico and Indigenous Resistance.

The Interoceanic Corridor project is promoted by the Mexican government as a multimodal dry-canal, an alternative to the Panama Canal, which intends to speed up and amplify the circulation of goods, and thereby simultaneously stimulate the local economy in southern Mexico. Pitched as a major development project by the current Mexican president, it is actually a megaproject that brings together a set of highly polluting extractive and agro-industrial endeavours, which, if fully implemented, would negatively transform the entire socio-environmental and cultural dynamics of the south and southeast of Mexico.

The Interoceanic Corridor project includes the following central components: a fast freight train with a parallel highway; the modernisation of the ports of Coatzacoalcos/ Veracruz and Salina Cruz/ Oaxaca (with deep dredging and expansion of breakwaters); the modernisation of the two refineries and petrochemical complexes in said ports; the construction of new gas and oil pipelines; the improvement of the regional airports to expand air traffic; the creation of 10 industrial parks (500 to 1,500 ha) for the installation and operation of industries from sectors such as the automotive (auto parts, transportation equipment), agribusiness (food, beverages and tobacco), manufacturing (leather, textiles, clothing), as well as transportation and logistics.

As with many other contemporary infrastructure projects, the Interoceanic Corridor is based on an extractivist and urbanising model of capitalist development, in which resources, benefits and wealth are transferred from one region to another. However, community visions of alternative infrastructures already exist.

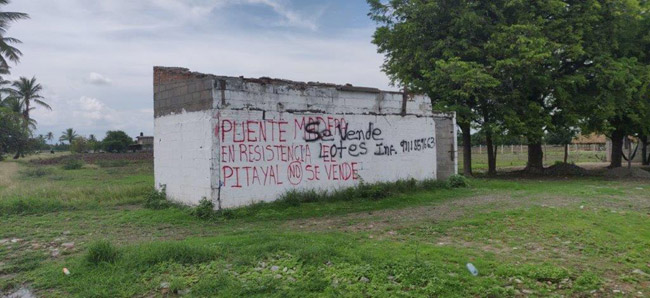

Social movements fear that this project will lead to an increase in private oil extraction from new deposits (conventional and by fracking) and an increase in concessions for open pit mining, both made possible by a colonisation process that involves an accelerated change in land use, which is currently the main cause of ecosystem degradation.

During the mandate of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the construction of critical infrastructure has increasingly become militarised. As of October 2022, the Mexican Navy (SEMAR) has been put in charge of the parastatal train company Isthmus of Tehuantepec Railways, a pillar of the project. Not only has the Mexican president increased the presence of elements of the armed forces in the region, but actually handed over the implementation, logistics and administrative power to the military. By consigning these assets to the Mexican Navy, the military now possess an autonomous financial resource, and therefore effectively more power than ever before. Social movement actors are worried about the implications of this for future resistance against the infrastructure project, and for the defence of land, natural resources, cultural survival and Indigenous forms of political organisation.

Located in the heart of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is the Chimalapas bio-region, a vast territory of 600,000 hectares, which is the ancestral property of the Zoque Chimalapa Indigenous people. It is the region with the greatest and best preserved biological diversity in Mexico and Mesoamerica. The region has been subjected to an aggressive process of invasion with impunity for more than 70 years, by loggers, ranchers, and drug dealers, from the neighbouring state of Chiapas, who have tried to dispossess the Zoque people of more than 160,000 hectares in the eastern part of the territory, devastating to date 50,000 hectares of rainforest and cloud forest. With support of the National Committee for the Defence and Conservation of the Chimalapas (CNDyCCh), the communities self-decreed their territory a Peasant Ecological Reserve (or Community Reserve) in 1991, a counterproposal to the intended imposition (by state and external actors) of a Federal Biosphere Reserve, which would deprive them of their sovereign right to decide on the use and management of their ancestral territory. The Community Reserve, as such, has not been recognised by the federal government, and with the arrival of the Interoceanic Corridor project in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, its status has again become subject to scrutiny and contestation.

As with many other contemporary infrastructure projects, the Interoceanic Corridor is based on an extractivist and urbanising model of capitalist development, in which resources, benefits and wealth are transferred from one region to another. However, community visions of alternative infrastructures already exist. The peoples in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region want infrastructure that is not imposed by the state, but chosen by the communities. Considering the cultural diversity of the region, where 12 different Indigenous peoples and afro-descendent populations live, infrastructures cannot be homogenous: they must be adequate and functional according to the social and cultural characteristics desired by each community. Additionally, local communities want infrastructures to maintain and/or improve existing ways of producing, relating and cohabiting, rather than wiping them out. In a public statement, a union of collective land holders, agricultural communities and Indigenous peoples from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region, sets out their infrastructural wants: hospitals, schools, basic infrastructures for drinking water, electricity, and drainage, reforestation and an investment into local agriculture that increases its productivity in line with traditional and sustainable farming methods. The top-down design of the Interoceanic Corridor currently disregards existing cultural models of life and social organisation.

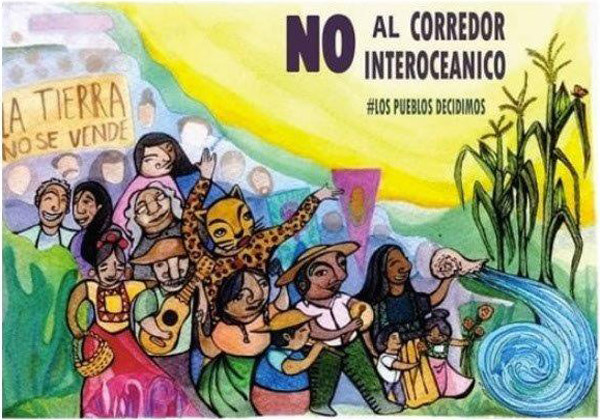

Indigenous and afro-descendant communities are the rightful owners of most of the territories in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. They have historically raised persistent resistance and built social organisations in defence of their territory, their culture, and their invaluable natural assets. Today, those communities require support and accompaniment, social commitment and financial resources, to peacefully resist the serious threat that this infrastructure project implies — ethnocide and ecocide — in order to build a comprehensive alternative, based on the proposals from those threatened communities.

Miguel Ángel García Aguirre, founder of the organisation Maderas del Pueblo, will be in Liverpool in February 2023 to meet interested organisations, collectives and individuals, and share his knowledge of the Interoceanic Corridor megaproject and how it impacts on the Chimalapas, one of the most bio-diverse regions on earth, and on the Indigenous peoples of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region in southern Mexico.

For updates on the upcoming event in Liverpool, check out the dedicated webpage on the Next To Nowhere (Liverpool’s social centre) website. There is also a Facebook event you can share.

For more information, read Miguel Ángel García Aguirre’s article Interoceanic Corridor in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec: native peoples, nature and national sovereignty under threat or watch this video by the National Committee for the Defence of the Chimalapas on the struggle of local Indigenous communities for land rights.

For keeping up-to-date with Indigenous resistance against this infrastructure project see the website of the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Oaxacan Isthmus in Defense of Land and Territory (APIIDTT).

Read a policy report on the Interoceanic Corridor infrastructure project and its impacts.

Listen to the Infrastructure Reworldings podcast to learn about different infrastructure projects in Mexico and beyond.

Fighting Big Infrastructure Projects in Mexico: Speaker and Film

Tuesday 21st February at 7pm

Next to Nowhere, 96 Bold Street, Liverpool, L1 4HY