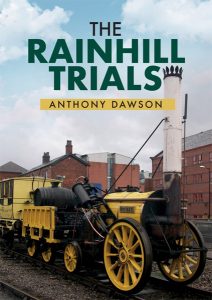

By Anthony Dawson

Amberley Press

£14.99, 96 pages

Reviewed by Joe Coventry

Consuming It’s Own Smoke

The author, a lifelong rail enthusiast, would not have had much prompting to write this book on the seminal moments that changed the world of transport for ever. It was in Rainhill, eight miles outside Liverpool from 6th to 14th October 1829 that the supremacy of the motive steam engine, as the fastest mode of travel on earth, was established.

Standing steam engines were being used in 1828 on the Stockton & Darlington Line were locomotives worked in conjunction with rope-pulled winding engines and horses. Now the search was on to test the efficiency of that form of motive power against free standing forms of locomotion.

Standing steam engines were being used in 1828 on the Stockton & Darlington Line were locomotives worked in conjunction with rope-pulled winding engines and horses. Now the search was on to test the efficiency of that form of motive power against free standing forms of locomotion.

A panel of judges selected the five entries to contest the Trials after an exhaustive weeding out process; The Directors of the Trial’s technical specifications were exacting but considered fair, even though not everyone was happy; but the contest went ahead to the excitement of an enthralled general public. On offer was a prize of £500 for the winner.

The field comprised Robert Stephenson and Henry Booth’s Rocket; Timothy Hackworth’s Sans Pareil; John Braithwaite and John Ericsson’s Novelty; Timothy Bernstall’s Perseverance and Thomas Shaw Brandreth’s (literally) horse-powered Cycloped. In the event the latter two were never at the races.

As every schoolboy worth his salt knows, Rocket won the day but not without claims of insider dealing, insufficient notice of the competition and non compliance of the technical specifications; lots of moaning in the press of the day added to the heat of the debate.

It was though the fuel efficient heat generated by the all consuming small bore 25 multi-tube boiler and air blast coke burning, self-contained copper fire-box of Henry Booth, (gleaned from ideas designed for a stationary boiler in 1784 by the French Marquis de Jouffroy d’Abbans), that was the leap forward. The engine also enjoyed an incorporated ‘dog clutch’ which enabled it to reverse, and there is much on the mechanics of p.s.i. boiler pressure, connecting rods, big ends, crank shafts and piston rods for those who want to know more; comprehensively, not just for Rocket but for the other contenders as well.

In the end it did not matter. Sans Pareil and Novelty were forced to capitulate due to a combination of leaking boilers, faulty water pumps and collapsed flue tubes as the winner diligently completed the designated 3 mile course (in 10 round trips), equivalent to the 30 miles between Liverpool and Manchester, at an average of around 25 mph.

As it went on to strut it’s stuff, in the Liverpool Mercury (6th November 1829) it was reported that ‘Rocket had drawn an astonishing load of 42 tons, ten times it’s own weight, 14 mph, which is by far the greatest task that has ever been performed by a locomotive’ in a staged PR exercise.

Its future assured Rocket made the opening cavalcade of trains on the world’s first intercity line, which opened on 15th September 1830. By the end of the year it was effectively obsolete as improved versions of its ground breaking design were introduced. That’s technology for you!

Dawson’s is a well put together book with beautiful illustrations, and although a tad technical on the mechanics maybe for the layman at times, is still worth persevering with.

Enjoy.