Immigration is a constant aspect of political debate and people seeking asylum very rarely have their say. Report by Vicky Canning

Anyone reading these words is likely to have already equated them to immigration. Without even needing to use the terms ‘migrant’, ‘refugee’ or ‘asylum seeker’, each term has become synonymous with a foreign ‘Other’, and conjures up images similar to those that Nigel Farage so proudly stood in front of in 2016… Masses of non-white people intent on reaching their new lives in Britain, at whatever cost.

Despite the political focus on the potential impact of the ‘refugee crisis’ on the UK, the reality has been very different. In a year that saw ‘unparalleled’ migration into Europe since the Second World War, only around 38,000 people made it to Britain to seek asylum in 2015. In the same year, 3,771 lives were lost in the Mediterranean, all trying to reach the safer shores of Europe.

Immigration is a constant feature of political debate, and people seeking asylum face a barrage of untruths about their lives and experiences. Over the past decade, while researching the British asylum system, one stark truth stands out: that the reality of asylum in Britain is not even vaguely reflective of what it is regularly portrayed to be.

As the words opening this article suggest, not much has changed with regard to the representation of migrants over the years, including those seeking asylum. You might already know that the ‘free mobile phones’ and ‘travel passes’ don’t exist. Neither do the ‘big houses’ or ‘fancy cars’. But more insidiously, neither does choice – choice about where you will live or whether you can work. For some, even choices about what your money can be spent on, where you can shop, or whether you can buy alcohol is limited or non-existent. All the things that are part of the everyday for most people are reduced or eroded.

The reality is that, in place of autonomy or wellbeing, is the constant spectre of social control. People seeking asylum are not permitted to work, and so are forcibly state dependent. The obvious problem this leads to is poverty: a single person is entitled to just over £36 per week – around half that of jobseeker allowance. As a GP working with refugees went as far as to say, ‘there are two systems of welfare for people in this country, one is for British people and one is for asylum seekers’.

Women I speak with are sometimes in physical pain from having to walk miles, hungry because they are forced to choose between food, travel and the wellbeing of their children. Just over £5 per day is supposed to cover toiletries, sanitary products and warm clothes as well.

In an era of food banks and increased destitution, we well know that poverty is not confined to asylum. As more and more people face job losses, violent austerity measures and increased financial uncertainty, poverty is commonplace. For people seeking asylum, however, the effects of poverty are often compounded by the threat of detention or deportation. Even attending regular Home Office signings can evoke anxiety.

In a focus group for a previous research project, one woman told me that, ‘They [Immigration Officers] speak to you, not like you should not be in the country, but that you should not be on the planet’, while another stated that in interviews, ‘You feel like you want to kill yourself. Just jump through that window’.

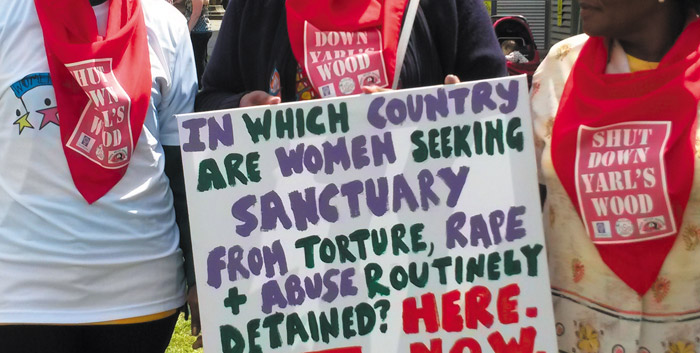

At any given time, a person seeking asylum can be detained at the Home Office, or transferred to one of Britain’s eleven Immigration Removal Centres (IRCs). Here, people can be held indefinitely in prison-like conditions, facing curfews and regulated daily procedures, which include headcounts. Some women in IRC Yarl’s Wood have likened their treatment to that of cattle. As women I speak with often point out, the fear of arbitrary detention adds to anxieties as the Home Office interviews approach.

Alongside detention, people are well aware of the most dangerous potential outcome: deportation to the country from which they have fled conflict, violent partners or persecution. Hawwi – a participant in oral history – was twice denied asylum despite having evidenced her own torture and abuse at the hands of her government. She concluded, ‘There is no way I am going to escape the eyes of the government, and there is no means of surviving there…. Deciding to return me there is killing me’. Most people who apply for asylum are refused, but Hawwi eventually gained the right to remain in the UK. However, the number of people who are subjected to torture or even death on return is unknown, since contact with individuals is often lost. Still, as Hawwi often stated, the fear of such a threat remains while people await the outcome of their asylum claim.

Supporting survival, or inflicting further harm?

People seeking asylum have often experienced highly traumatic events, including conflict, death, abuse in detention, to name just a few. Instead of holistic support, however, people are more often left in poverty with minimal practical provision. Some face racism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, or all three. All of these have the potential to make the impacts of trauma – such as depression, sleeplessness, chronic fatigue and nightmares – much, much worse.

Over the years I have spoken with women survivors who have been raped by border guards, husbands or partners, and militia. A psychologist who had been supporting survivors of torture for 18 years told me, ‘They may have been raped in conflict, raped as a method of torture. Many of the women who visit here have come from rape camps in Central Africa. They’ve been raped more times than I can even imagine.’

For anyone seeking asylum, the stress and uncertainty of the system can have serious effects on people’s mental health and emotional wellbeing. For women – a group commonly affected by sexual violence, domestic violence and sexual torture – the process can make the impacts of violence even worse. And yet women are routinely disbelieved, particularly in instances of sexual or domestic violence. This is well recognised by survivors of violence, with one focus group participant arguing that, ‘Women are not believed. They want to see your corpse. Until then they won’t believe it.’

The reality of people’s lives in asylum is one of limbo. Women and men are left to fill time – sometimes years – with endless battles for refugee status, and limited autonomy over daily life and, like Hawwi, sometimes feeling that, ‘There is no way we are coping with life, and it is very, very hard really. It’s very hard.’

As a society, our eyes are trained on asylum seekers as spongers, taking jobs from British workers and existing on benefits paid for by taxes. People can’t ‘steal’ jobs, because they are not permitted to work. The benefits people receive per week amount to just under half of what it takes to detain someone in an IRC per day and yet more than 33,000 people were detained last year alone.

Perhaps it is time to truly challenge myths around asylum and immigration, to collectively reject negative assumptions, and not only for the wellbeing of those who are in the system. For as long as we continue to train our focus on those who are amongst the most powerless in society, we are deflected from what is happening amongst the most powerful. While we as a society squabble with people seeking asylum over the £36 they receive a week or free NHS prescriptions, politicians and corporate executives are profiting from immigration detention and building borders.

While we continue looking down, those above our heads are facilitating a wholesale dismantlement of the very welfare systems that some of the poorest and least powerful people lean on to survive, and that includes people seeking asylum.

Victoria Canning is a feminist asylum rights activist, and Lecturer in Criminology at The Open University. She is presently researching the gendered harms of seeking asylum in Britain, Denmark and Sweden.

Her latest book, Gendered Harm and Structural Violence in the British Asylum System, has recently been published.