| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Niet Normaal

– Difference on Display

Niet Normaal

– Difference on Display

The Bluecoat, Liverpool,

Friday 13th July to Sunday 2nd September 2012

AGREEMENT AND DIFFICULTY - A Review by Minnie Stacey

This exhibition is part of The Festival of Disability and Deaf Arts, and brings together work from 24 artists. The show is designed to make us question the everyday superficial judgements we make about other people and does succeed in this, despite not achieving the perfection of its declared vision.

One of Niet Normaal’s first features is a film. Javier Téllez’s 27.7 minute Caligari und der Schlafwandler (Caligari and the Sleepwalker) pays homage to Robert Wiene’s famous expressionist film Das Kabinet des Dr Caligari from 1919. However, in Téllez’s version actual psychiatric patients play the characters and in some scenes they are the general public. The film is framed as being inclusive and human with the actors revealing what they like to do in their own lives, and the patient who has written the script introduces the film by telling viewers that the drama has deliberately increased the distance that already separates us and therefore won’t worm its way into people’s minds. In the absurd and theatrical scenes that follow, poignant questions about our attitude towards mental illness and learning difficulties are raised: Are we always categorising people as normal or abnormal? Are we all the prisoners of ‘voices’? ‘Why should communication be so difficult? Deft, wry and bright-eyed, this is a successful art film that entertains whilst holding up a mirror to our outlook on difference.

The next room is dominated by a vast glass-covered table showing a collection of 14,000 colourful pills. Cradle to Grave II by Pharmacopoeia, is based on a study into the use of medicines by the average Dutch person. Around the edge of this hard-to-take medical hegemony is a border of photographs from family albums with snapshots of people living ordinary everyday lives. Children frolic on the beach, people slice wedding and anniversary cakes while holding the camera’s gaze and a woman stares out with a budgie perched on her shoulder. It’s frightening to think that even relatively healthy lives can be a clinical progression mitigated by medication, and Cradle to Grave II makes you question how authenticity is affected by this growing harness on human behaviour.

A video nearby slows down scenes and repeats them as rhythmic sequences in Douglas Gordon’s 10.37 minute 10ms-1. According to the exhibition plaque, this technique is meant to “shift our attention from a perverse voyeurism to a more neutral, respectful observation of the complexity of the human body and mind”. But I couldn’t get over the humiliation of a semi-naked man who is unable to stand, being presented as art and stuck in a film on public display attempting to get up again and again with nowhere to hide from an eternity of eyes. The ‘found’ footage is of unknown origin and dates back to World War 1.

Similarly – though more recent and therefore subject to consent – across the room Imogen Stidworthy’s I Hate, veers towards controversy with its cold presentation but makes you think about the struggle with difficulty. It explores the relationship between thought and language with a man painfully trying to recover his voice via speech therapy. The strain of producing words is also accessible as vibrations via transducers.

In a DaDaFest brochure, a stated aim of Niet Normaal is to make us question a world that is “not always as inclusive and democratic as we would wish for”, and perhaps the art of not treating people with respect is evident in Christian Bastiaans’ reflections on the gaping wounds of raging civil war in Sudan, Uganda, Chad and Sierra Leone. Made out of gauze, shiny pink and white silk, and mosquito nets, his “hurt models” for Microbe Mutilate Messiah and Körper sur Beobachtungsstation are far too flimsy and ephemeral to foreground the suffering that real people are enduring. Even the text of one of their harrowing stories printed on such slight fabric is difficult to read and easy to miss. As an example of a medium not delivering a message it replicates the scant media coverage this subject is given.

If we’re meant to review our perspective on people in Niet Normaal, they are strangely absent from some of it. A deliberate distance is created in the spartan, unpeopled, cell-like rooms of Ricarda Roggan’s Das Zimmer. There’s a disappearing man in Floris Kaayck’s pseudo-documentary Metalosis Maligna, which is too far out and comical to play on “the collective fear of foreign bodies and standard responses”. Jana Sterbak’s Monumental shows an oversized replica of two crutches without an owner and leaning against a wall, which are of no use to anyone but do start you thinking about the pointless and myriad props we can all turn to.

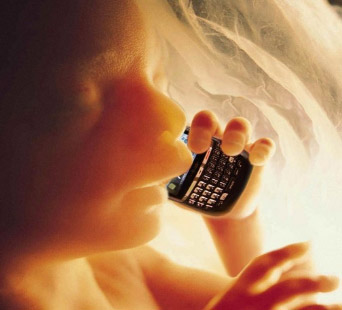

Niet Normaal’s textual signposts, through which we’re meant to look at this exhibition, can be at odds with the work. The 81 parts in Amsee Perera’s Screen are labelled as “pods that call to mind foetuses or forms of natural growth and suggest issues concerning genetic screening and the identification of disease genes”, yet on first sight could be said to look more like a variety of decorated biscuits. Birgit Dieker’s limbless sculpture Bad Mummy is meant to make us question provocative sexual fantasies and motherhood. It’s a powerful piece, but without this explanation the premise wasn’t obvious to me.

Playing with language and the presentation of meaning is an overall focus of Niet Normaal, where normality shifts in a spectrum of perspectives. Ben Cove’s clichéd words in the central room saying “EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT” appear to have fallen down and lie at odd angles in a crash of communication. Christine Borland’s Cast from Nature has a hollowed out plaster and metal figure looking like it’s pulled a ripcord on its own body and become a parachute of descent with a strange, exhilarated face.

The final exhibit cleverly puts humanity back together, with Karin Sander’s Body Scan. The artist scanned visitors to a previous exhibition in Amsterdam and reproduced exact, small replicas in a 3-D printer. Albeit it virtually produced, this display shows us ourselves. Painted in warm colours and with exquisitely precise and detailed expressions, smiles and stances – whether in wheelchairs, on sticks, healthy, sick or without impairment – we are all here!

Twitter: @minniestacey