| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

James McNeill Whistler Exhibition

A Needle Walks into a Haystack: Liverpool

Biennial 2014

The Bluecoat

5th July – 26th October 2014

Free entry

Reviewed by Sandra Gibson

“I forgot everything in my joy of it.” James McNeill Whistler 1834–1903

Don’t expect to meet Whistler’s mother! This exhibition introduces works less well known and understandably focuses on the relationship between the painter and his patron Sir Frederick Leyland, the Liverpool shipping magnate whose portrait appears in the publicity. What was Whistler thinking of, producing such an offensive satirical study? The Gold Scab (1879 - below left) depicts Frederick as mad-eyed and reptilian. Well - they’d fallen out by then and the recreation - by Olivia du Monceau - of Whistler’s Peacock Room as part of the show holds the Catherine of Aragon-related melodrama. Briefly: interior architect Thomas Jeckyll had created an impressive dining room for Sir Frederick’s London house; Whistler’s painting La Princesse du Pays de la Porcelaine (1863-1864) was over the mantelpiece and there arose a concern that the red roses in the leather hangings clashed with the colours in the painting. So Whistler was given permission to retouch the walls with traces of yellow. Leaving the artist with these minor amendments, Leyland returned to Liverpool.

Agreeing to let Whistler make minor adjustments was the same as telling Laurence Llewelyn Bowen he could only choose the cushions. It just wasn’t going to happen. He got carried away with his own intentions and covered the ceiling in imitation gold leaf over which he painted peacock feathers; he gilded Jeckyll’s walnut shelves and embellished the shutters with peacocks. “I forgot everything in my joy of it,” he said. Well yes he did - he painted over Queen Catherine’s sixteenth century Cordoba leather: the very same that Sir Frederick had paid a thousand quid for.

|

|

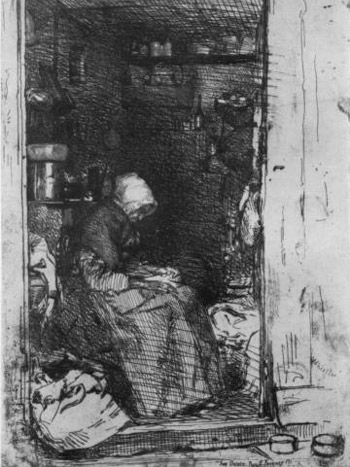

| The Gold Scab (1879) | La Vieille aux Loques (1858) |

And oh the innocent irony of his letter, urging Sir Frederick not to return before he had finished : “I assure you, you can have no more idea of the ensemble in its perfection gathered from what you last saw on the walls than you could have of a complete opera judging from a third finger exercise!”

Sir Frederick was incandescent and Thomas Jeckyll had a nervous breakdown. Not only had the artist gone beyond his makeover remit, he had opened his sponsor’s house to visitors and the press and there were rumours of an affair with Lady Leyland. Sir Frederick refused to pay the two thousand guineas Whistler wanted, eventually paying half but in pounds as if the artist were a tradesman. Whistler had the last word, immediately and historically. He painted a mural of two peacocks in stand-off mode, the withheld coins at the feet of one of them. Displayed opposite La Princesse, he called it Art and Money. “My work will live when you are forgotten,” he said. He was right, The Peacock Room, which he called Harmony in Blue and Gold (1876-1877) is considered a high example of Anglo-Japanese style, anticipating the decorative patterning of the Art Nouveau style of the 1890s. Significantly, Sir Frederick Leyland kept the room as Whistler left it. It ended up in America, which the artist had left for ever, aged 21.

The Peacock debacle has illustrative diversity: it exemplifies the precarious relationship between artist and patron and it highlights the pervasive ignorance about Whistler’s artistic aims, which he pursued in such a single-pointedly passionate way. Any exhibition of his work had an immersive quality: paintings, positioning, exhibition space, lighting - even the clothing of the gallery attendants - were conceived as an aesthetic whole. An artist with such an aspiration is hardly going to collaborate with anyone else or settle for a few amendments in yellow. “The visitor is struck, on entering the gallery, with a curious sense of harmony and fitness pervading it, and is more interested, perhaps, in the general effect than in any one work,” a reviewer said. And it is just this experiential ambiance that the Bluecoat exhibition demonstrates in the small gallery full of blue dusklight through which the works are dimly seen. Sunrise; Gold and Grey (1883 -1884) is a water colour whose subject is light and colour – not form. The same de-emphasis of form is found in a second water colour: Nocturne in Grey and Gold - Piccadilly (1881-1883 - see below). Fog and mist and failing light dissolve emerging forms and patches of pale gold from shops and houses to the side are echoed in the integral gold frame. The experience of this gallery is of walking about in a Whistler painting. Lovely.

|

| Nocturne in Grey and Gold - Piccadilly |

The same sense of harmonious achievement doesn’t hold for the Peacock Room because although the rich turquoise and gold pleases the eye, it doesn’t do what it says on the tin. It is not, in my opinion, harmonious. You don’t need to know about the falling out to sense the oppressiveness of the power struggle. The lack of movement in the peacock confrontation does not produce the balanced stillness we look for in Whistler’s work because it is not still; it is static. We know from his pen and ink sketches of Loie Fuller dancing that Whistler can create movement with a delicacy of touch. But there is no delicate touch here. The work lacks grace because Whistler has broken his rules: “Art should be free of all claptrap - should stand alone and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like. All these have no kind of concern with it, and that is why I insist on calling my works ‘arrangements’ and ‘harmonies’.” As Robert Hughes said, “The story was that there was no story”. One of the paintings in the Bluecoat exhibition reveals the painter’s intention very well; Miss Rosalind Birnie Philip Standing (1897) is an oil painting more about the quality of dense blacks, greys and golds than it is about Rosalind’s personality or beauty.

But in painting the peacock narrative Whistler has allowed narcissistic ambition and antagonism to pollute his aestheticism.

It’s easy to overlook Whistler’s prowess as a draughtsman; we are accustomed to thinking about his Nocturnes and his sumptuous portraits where colour is the issue. Yet he was highly regarded for etchings created in Venice and London and there’s a nice selection at the Bluecoat. The tedious map-making work of his early years paid dividends and using the skill of meticulous application, he has produced such a feeling of stillness and atmospheric power in his subjects that they are distanced from us by more than time. And this stillness is not just to be found in the inanimate objects such as boats and buildings depicted; portraits such as The Fiddler (1859) also have it. The face is emphasised and there is not a muscle moved to play the instrument, which is merely suggested. La Vieille aux Loques (1858) is particularly striking in its mysterious secrecy of being. Wapping (Rotherhithe) (1860) has two kinds of historical significance for the modern audience: it’s a riverside view of Victorian London and it’s an example of the influence on Whistler of Japanese composition. The characters are not shown centre-stage and whole; like Degas he has cut them off as often happens in a photograph and the boat riggings are equally important components in making the composition.

You can’t help but be drawn towards someone who was dismissed from the US Military Academy at West Point for “deficiency in chemistry”, who lost his map-drawing job because he drew mermaids and whales and sea serpents in the margins, whose girlfriend was the model for Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde (1866) and who collided with the art establishment with such bloody-minded passion that he took John Ruskin to court. It’s easy to get side-tracked into the nineteenth century road movie that was often Whistler’s life but he was an immense figure in the development of Western art. He had the courage to walk his talk and the passionate conviction not to be floored by ridicule. He was a pioneer in the movement towards abstraction, in the acceptance of colour as subject and the concept that art and its environment are one. His public life might have been tumultuous and financially precarious but his inner conviction was harmoniously tranquil and beautiful, otherwise we wouldn’t have the Nocturnes.

Worth a visit just for the dusk-filled room.