| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

The

Gappalioness Monkey Project

The

Gappalioness Monkey Project

Carl Fletcher

Fallout Factory, 97 Dale

Street Liverpool

22nd February – 12th March 2013

Free entry

Reviewed by Sandra

Gibson after a conversation with the artist

Photographs of the exhibition by Geoff Edwards

A series of works inspired by the current situation of the world

Artist Carl Fletcher is part of the growing protest movement against consumerism. Recycling and subverting capitalism’s products, slogans and cultural preoccupations, he favours collage which has an immediacy compatible with being current and believes art “feeds your soul”. Having “the average Joe in the street” in mind when he produces his work, he doesn’t sell it even though people want to buy it, because recalling pieces for an exhibition is so much trouble and showing his work is a priority. Surrounded by his art Carl feels proud and sometimes angry because he sees things he could have done better.

A frame is an announcement of something set apart from ‘ordinary’ life, something to which the framer wants to draw attention. Carl Fletcher’s work is strikingly, often elaborately framed and displayed. Some small works, with tiny figures blurred by pieces of reclaimed glass: bead-edged or gold-edged, are displayed against backgrounds of velvety black. Drawn in, to look carefully, you find images from the obscured world of the sex worker. The message is complex: what is the aesthetically attractive presentation celebrating? Not this tawdry exploitation. I think that the artist is bestowing respect on the human victims caught up in a world of brutish capitalism at the same time that he places them in dark cosmic space.

In many of Carl’s collages, visual imagery from our newspapers and magazines and advertising copy exists side by side with the written word. Firstly there is the aesthetic value of word shape and font style, irrespective of meaning or sound. Then there is the political point about the power of the word in advertising, in propaganda and in the promotion of our cultural icons. Finally, there is the personal detail that Carl is a dyslexic who has embraced and celebrated words, cramming them in amongst his images, coordinating the compositions by the use of gel pens, giving a gaudy glamour but - crucially - also catching the light.

|

|

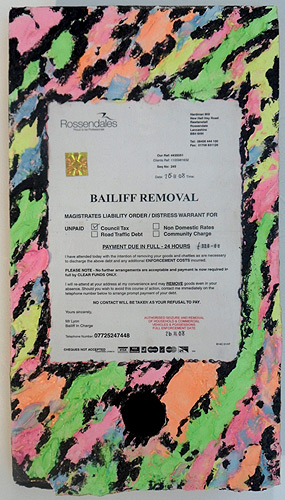

From this room of small images, some larger images stand out: a foetus, a gas mask, barbed wire, old black and white photographs having a contrasting stillness about them, squashed drinks cans. Carl has been particularly influenced by the packaging of an alcoholic drink called White Storm, whose power colours and motifs bring to mind the sinister energy of Nationalistic regimes with their dehumanising propaganda machines. If the exhibition were a film you would say White Storm was a key image. Not only does it reverberate with oppressive power, it also references the self-destructive addictions we espouse. A collage, The Gun Show consisting of squashed drink cans has a toy gun attached so you can shoot at the exhibit. It’s one way of expressing your feelings about this scourge but there is also a fairground fun element in doing this. Love Life, another potent image for our times shows a vandalised cash machine, in a frame of fifty-pound notes, being used as a repository for rubbish. A Bailiff Removal Notice for unpaid council tax also receives Carl’s customary framing treatment: in Black Hole the brightly coloured surround subverts the authoritarian tone of the document, sending it into the deeper recesses of space.

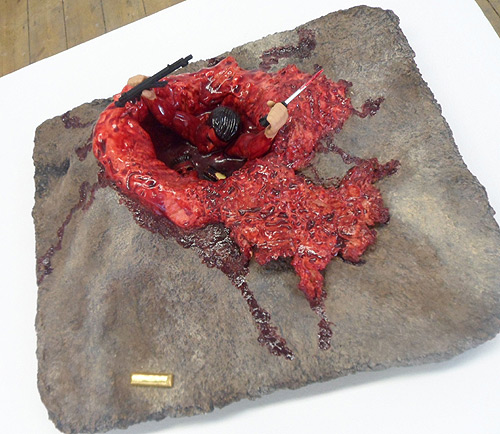

One of the most arresting exhibits is something resembling a flesh wound or the top of a volcano out of which an armed man appears. It’s a comic book sight made more alarming because it is three dimensional and it has a red, glistening visceral quality. Another three-dimensional work incorporates a dominating piece of tree branch: the small objects subjugated, including a small plastic car, look as if they come from children’s games. They appear elsewhere in the exhibition: fragments of jewellery, tiny toy guns, trinkets from crackers, gold chains …

|

And it is this element of careful miniaturisation that characterises Carl’s meticulous work. Anyone who has seen the fanatic gleam in the eye of a model railway enthusiast knows that this has something to do with needing a manageable world or - as in the case of the Chapman brothers - drawing you in closer to the horror of what is portrayed. And this might be relevant as a comment on Carl Fletcher’s work but I think there is a bigger reason: an awareness that we are part of something vast. “All we are, is a space-ship in space … That’s my religion - the cosmos … All religions worship the heavens in one way or another.”

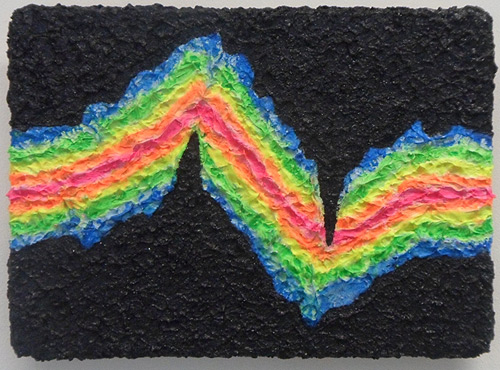

His pessimism about the fate of the human race - “I don’t think we’ll see another hundred years” - is tempered by the optimism we find in his brightly decorated work and his use of rainbow motifs: “The rainbow being a symbol of optimism and hope." *

Carl Fletcher is concerned about the state of the world but his feelings are channeled into creative transformation; he is a gentle, playful revolutionary who celebrates the global smile at the appearance of a rainbow, but whose eyes are also raised to the stars.