| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Paul Du Noyer’s The Art of the Album Cover

Little

Atom Productions

Little

Atom Productions

The Bluecoat

Thursday 20th September 2012

Reviewed by Richard Lewis

Former NME scribe and the founding editor of Q and Mojo, Paul Du Noyer’s presentation/lecture The Art of the Album Cover pays homage to one of the most celebrated and well-known by-products of popular music’s dominance over the 20th Century.

Considered by some to be a dying artform as music moves online, album covers in the vinyl and to a slightly lesser extent the CD age were hugely important to musicians and record companies alike.

Along with providing an eye-catching image to sit amongst the racks in record retailers, album covers were an essential part of establishing or cementing an artist’s identity, a paramount factor in an era before music videos and the Internet.

Inspired by a talk he gave at The V&A and a feature penned for The Word magazine, the event held at a packed exhibition room at The Bluecoat sees Du Noyer, aided by a simple power point presentation pay tribute to what he dubs ‘The People’s Art Gallery’.

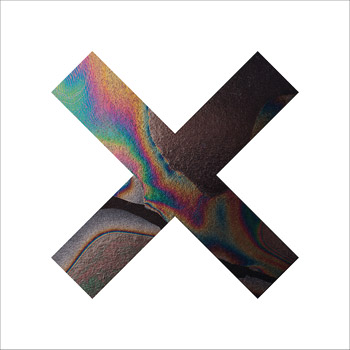

Beginning with a comparison between arguably the most famous LP cover of all time Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Du Noyer contrasts the meticulously detailed artwork cover of The Beatles’ 1967 opus to X, the Mercury Prize winning 2009 debut of electronic trio The xx.

Beginning with a history of the ‘album’ prior to the advent of recorded music, Du Noyer cites 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys (himself a keen musician) as possibly the first connoisseur of album sleeve art via his collections of sheet music including his own compositions, housed in illustrated jackets, arguably the earliest albums covers.

The advent of sheet music publication of collections of popular songs and stage shows in the 19th Century meant albums were now tangible artefacts, the accompanying cover art work, the earliest definable album sleeves.

With the arrival of long playing records in the 1940s, artists and record companies realised that the covers to the discs could be far more appealing to potential buyers if they were packaged in more than just a plain paper sleeve.

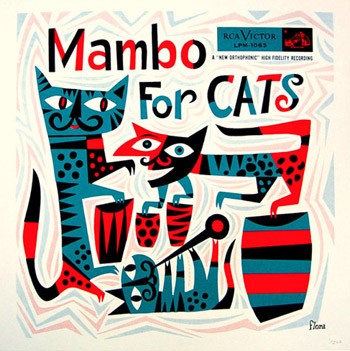

Jim Flora, dubbed by Du Noyer the ‘Godfather of the album cover’ was one of the first to receive recognition for his work in the field with his highly imaginative sleeve designs for CBS Records and RCA Victor in the 1940s and ‘50s for jazz and classical artists, including LPs by jazz great Louis Armstrong.

During the same decade the notion of album covers acting as a personal statement for whoever was seen to be carrying one, began to cement itself.

This practice effectively led to the formation of The Rolling Stones after Mick Jagger and Keith Richards struck up a conversation after the guitarist spotted the future vocalist on a railway platform carrying a Muddy Waters LP.

The very fact that Jagger had the album, available only on import in the UK was a distinct badge of cool, a trend that continued throughout the decade and into the next as long-haired music fans in Afghans or greatcoats with an album tucked under their arm were a commonplace sight at gigs.

The Beatles’ commissioning of famed pop artists to create sleeves for them, demonstrates how seriously the artform was being taken by the mid to late 1960s, with Peter Blake designing the cover to Sgt. Pepper and Richard Hamilton providing artwork for the following year’s eponymous double LP (aka The White Album).

The

impact of the influence of art school students on music Du Noyer suggests

reaches its apogee with the striking, model-adorned covers for Roxy Music

first five albums from 1972 to 1975.

The

impact of the influence of art school students on music Du Noyer suggests

reaches its apogee with the striking, model-adorned covers for Roxy Music

first five albums from 1972 to 1975.

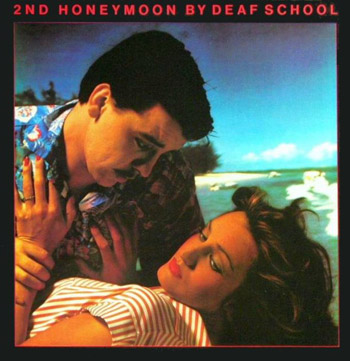

A bunch of fellow art students from the same era, Liverpool prog-pop band Deaf School are cited for their debut album 2nd Honeymoon (1976) (pictured right), which introduces the idea of breaking through the fourth wall.

An image of a couple embracing, the back cover reveals the mise-en-scène behind the shot, staged in a photographer’s studio, a clever piece of deconstructionism possibly cribbed by Sheffield band ABC for their 1981 debut The Lexicon of Love.

During the music industry’s boom years in the 1970s when Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and Fleetwood Mac created LPs that sold upwards of ten million copies within a few years of their release, album covers became some of the most widely distributed pieces of visual art in the world.

Where artists had previously toyed with a certain type of mystique in the presentation of their music, David Bowie in particular understanding the power of strong visual presentation, Thriller released in 1982 put a premium on instant artist identification.

By a colossal distance the biggest selling album of all time, the cover featured a simple photograph of a besuited Michael Jackson and revived the concept of album covers where the artist was immediately clear to the buyer.

The arrival of the CD in the mid 1980s meanwhile leads to what Du Noyer terms ‘small space, big face’ covers, due to the decreased size of the format, the available space shrinking from twelve inches square to less than half that for the five inch booklet covers.

This trend, preferred by solo artists continued through the 1980s and early 1990s saw artists as diverse as Bruce Springsteen, Madonna and Morrissey releasing several albums that featured themselves as the sole image on the cover.

While the ongoing boom in digital album sales has to some extent revived the music industry and with streaming becoming more prevalent, the accompanying artwork has changed to keep pace.

As music moves increasingly online, with even more people now viewing album artwork via computer screens displaying chart rundowns and online retailers like Amazon, the artwork itself has conversely become far less important Du Noyer argues.

With

the display screens on iTunes and streaming site Spotify dominated by

the album’s song titles, album artwork is crushed into a one-inch

square icon in the corner of the screen.

With

the display screens on iTunes and streaming site Spotify dominated by

the album’s song titles, album artwork is crushed into a one-inch

square icon in the corner of the screen.

Bringing the presentation full circle, the writer points to the LP covers of The xx, whose debut album X featured the title/band logo in a white on black sleeve and nothing else besides. Follow-up Coexist (2012) (pictured right) meanwhile adopted exactly the same formula, albeit with a different backdrop, sleeves that are easily recognisable, no matter how small the depiction of it is.

Interspersed throughout the presentation live music from superlative folk/country duo The Big House covering songs from several of the albums discussed is performed, in what is sadly their final gig.

Unplugged interpretations of classics Breathe from Pink Floyd’s The Dark of the Moon (1973), She Belongs to Me from Bob Dylan’s Bringing it all Back Home (1965), Sunday Morning from The Velvet Underground and Nico (1967) and Will You Love Me Tomorrow? from Carol King’s Tapestry (1971) all feature.

A fascinating, thought-provoking exploration of a medium once widely taken for granted by music fans, Du Noyer’s presentation is timely as by the end of the decade with streaming becoming the format in which many people listen to music, album covers in the traditional sense are likely to have been replaced by new alternatives.