| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Art

in Revolution

Art

in Revolution

Liverpool 1911

Walker

Art Gallery

24th June – 25th September 2011

Free admission

Reviewed by Sandra Gibson

The exhibition marks two anniversaries: a transport strike that crippled Liverpool in 1911 and the Sandon Studios Society’s exhibition of Modern Art, including work by the Post-Impressionists and British artists, in the same year. The underlying premise is that the revolution in art paralleled the drive for political and economic change.

From a twenty-first century perspective it’s impossible to share the sense of excited liberation experienced by artists influenced by, and exhibiting with, such pioneers of modernism as Gauguin, Matisse, Cezanne, Picasso, Van Gogh, Signac and Serusier. But the exhibition was significant on two counts: it selected about 50 works from the London exhibition and brought them to Liverpool, linking them with what was happening culturally there and consolidating its opposition to the views and practices of the art establishment. The exhibition, held at the Bluecoat, formerly known as the Liberty Buildings, also coincided with a period of political and economic upheaval.

Art in Revolution is an attempt to recreate that exhibition alongside archive material from the Liverpool strike of 1911.

For me the 2011 exhibition is dominated by the depiction of the social unrest on the streets of Liverpool which so unnerved the government that they dispatched troops and stationed a warship in the Mersey. Even George V felt moved to telegram his Home Secretary Winston Churchill: “Accounts from Liverpool show that the situation there is more like revolution than a strike.” Perhaps it was - in some jittery minds - but witness statements imply exaggeration, panic and over-reaction from the authorities. The usual story.

The large installations of photomontage, based on the series of 80 post cards Carbonora produced of the dramatic events, occupy the exhibition’s centre, dwarfing the art which literally (and metaphorically?) is on the periphery. The black and white photography, together with the enlarged statements and the use of red with its political resonance, creates a dramatic tabloid effect and this is increased by the use of (repeated) film of the event. (The newsreel was edited at the time by the authorities to remove any instances of police violence.) The pictorial impact of all this is substantial, mesmerising, even. The larger-than-life people, the massed citizens of Liverpool moved on by the regimented power of police and troops, the trams and escorted carts of goods, the ubiquitous horse power, the class system shown in dress and in the stranded passengers incapable, it seems, of carrying their own luggage and the recognizable landmarks of the city all contribute to the spectacle, which if you are a Liverpudlian must be underpinned by a feeling that your own ancestors could be there.

So how can the artwork from the Sandon exhibition compete? Does it have to? It has a quieter statement – it’s smaller and it doesn’t move about on horseback, for a start. It hasn’t been enlarged for effect; it has to speak with the voice it started with. I suppose for the viewer it’s the difference between seeing the edited highlights of a momentous event and then having to make an intellectual effort to read a piece of erudite background material. And a mind that is accustomed to portraits being painted with broad spontaneous strokes, landscapes being suffused with the colour of the artist’s emotions, perspective being played about with, the paintness of paint being affirmed and the relentless movement towards abstraction, it takes some effort to discern the revolutionary effects on painting represented by the Post-impressionists. The modern eye is not offended when Augustus John pays scant regard to the detail of a watch chain and it’s hard to believe, but in 1911 most people would be.

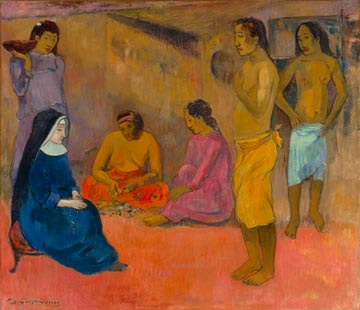

You can see the influence of Gauguin and Serusier in Charles Mackie’s atmospheric woodcuts. The areas of flat colour and the characteristic hard-edged cut-out style of their work are echoed in Ducal Palace, Venice and in Palace Gardens, Venice. But looking at Gauguin’s Breton women and his use of mood-inducing colour in Sister of Charity (top) and observing the confidence and commitment in Paul Serusier’s flattened landscape, La pluie sur la route, with its bold linear effects and attention to composition, one feels that Mackie is still rather a tentative rebel.

In a ‘before and after’ duo of paintings by Dalziel McKay we see something of the effect of Post-impressionism in the treatment of subject. Her 1906 painting The Ebony Cabinet is conventionally realistic with a fairly sombre palette; Through Green Transparencies shows greater fluidity, some lightening up and a few expressionistic Van Gogh swirls.

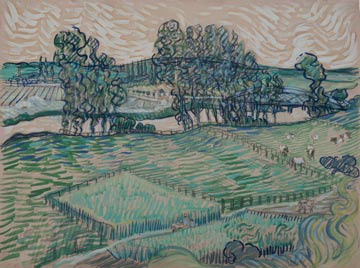

It’s

interesting that in Albert Lipczinski’s painting The Drinker, the

decorative, heightened brushwork is as important a factor as the subject

himself. In his strong portrait of Elizabeth Yates the free, loose style

of the brush adds vitality and decoration and this attention to expressive

technique is surely derived from the Post-impressionists. Just look at

the linear communication in the trio of Van Goghs displayed in a row at

this exhibition: the contorted tree trunks and sense of turbulence in

the Saint Remy drawing, the sense of directional flow in The Oise at Auvers

painting (right) and the approach to abstraction (and death, as it happens)

in Hayrick.

It’s

interesting that in Albert Lipczinski’s painting The Drinker, the

decorative, heightened brushwork is as important a factor as the subject

himself. In his strong portrait of Elizabeth Yates the free, loose style

of the brush adds vitality and decoration and this attention to expressive

technique is surely derived from the Post-impressionists. Just look at

the linear communication in the trio of Van Goghs displayed in a row at

this exhibition: the contorted tree trunks and sense of turbulence in

the Saint Remy drawing, the sense of directional flow in The Oise at Auvers

painting (right) and the approach to abstraction (and death, as it happens)

in Hayrick.

John Lavery’s Anna Pavlova as the Dying Swan is a fine portrait with loose brush strokes and effective depiction of light reflected in the head ornament and dress. He was criticised for his lack of form but surely the modern critic would praise the ethereal effects.

But none of the British painters approach Picasso’s radical portrait of dealer Clovis Sagot which is well on the road to Cubism. Just compare this with the rather conventional portrait Frank Copnall did of the Walker Gallery’s curator. Not to mention the fact that Picasso had already achieved the unthinkable in Les Demoiselles D’Avignon which was produced before the portrait of Sagot.

Although we find elements of Impressionism, Expressionism, Pointillism in such paintings as Henry Carr’s The Mersey, Phillip Wilson Steer’s The Horseshoe Bend of the River Severn and Enid Hay’s richly textured Interior and note that Mary McCrossan was influenced by Gauguin and James Herbert MacNair’s decorative piece Psyche at the Well of Forgetfulness is Chagall-like, or that the almost monochromatic work The Falling Star by James Hamilton Hay reminds us of Whistler, none of the British painters have approached abstraction or de-emphasised ‘realism’ to the extent that Auguste Herbin – now obscure but at the fore-front of radical art then – does in Landscape Near Cateau-Cambresis. It’s the same with Andre Derain’s powerfully tense Trees Near Martigues, which has been formally simplified to the point of abstraction and Matisse’s Copper Beech Trees near Melun, which addresses the issues of pattern and composition as much as - more than - the objective trees.

These Brits have taken some of the ideas on board – but what kept them? They produced some nice paintings. Nice? I’ve just damned them with faint praise. But there is a sense of restraint that keeps them from manning the barricades of radicalism. They needed to chuck a few bricks. It’s hard to accept that the Rev. Lund’s observation: “Anarchy in the paint pot mutiny in the brush” in the Post-impressionist debate, 30th March 1911 could refer to this genteel work.

A truly cataclysmic revolution with a global canvas was only three years away.