| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Fight for

Justice in Guatemala

Fight for

Justice in Guatemala

By Juliette Doman

I went to Guatemala from Liverpool last year - to help support witnesses in their search for justice. I worked as an acompañante (international accompanier) - staying with and visiting witnesses and their families, and writing monthly reports on the human rights situation in the region I worked in. The presence of an international observer - who can monitor the situation and alert human rights networks if human rights abuses take place - helps deter such abuses. It also helps to combat impunity (literally 'lack of punishment') for the perpetrators of such abuses.

During my time in Guatemala I had many amazing experiences. I climbed up (and ran down) a volcano that was 3230m above sea level, visited Tikal (an ancient Mayan city surrounded by rainforest) and climbed up one of the seven pyramid-temples where the Mayans used to worship and make sacrifices to their gods over a thousand years ago. I jumped from 100 foot into a lake surrounded by mountains and volcanoes, and took part in a Mayan ceremony performed by a sacerdote (shaman) from 5 am until sunrise. In the high mountains of Huehuetenango the only light at five in the morning came from the fire and the candles and incense the sacerdote burnt. Part of the ceremony was to ask for blessings and protection of the witnesses in the genocide cases against the two ex-dictators, General Lucas Garcia and General Rios Montt. It was amazing to experience it, yet even more amazing to me was the courage and strength of the witnesses themselves - who had survived the most terrible experiences and refused to be silenced.

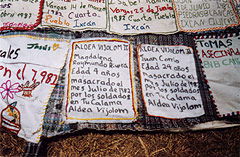

Being an acompañante is a strange job. I mostly spent my time chatting with witnesses, playing with local children (who found us fascinating - like aliens from outer space maybe!), walking between the seven different mountain communities I accompanied and trying to learn a few words of the local indigenous language (there are 23 different indigenous languages in Guatemala). Sometimes it was surreal - one day I found myself explaining how an electric coffee maker works, and what it was - in a community with no electricity! Sometimes it was sad - like one day I helped with the preparations for a march in the capital for the Day of the Victims. The relatives of massacre victims made embroidered cloths to commemorate each person who was killed - with their name, community and date and place of the massacre. The cloths were then sewn onto banners to be carried during the march (see photo). I wrote out some for one community because there was no-one else there who could write (the majority of indigenous people are either illiterate or have literacy problems). I felt honoured to be asked but also writing them made me sad - writing the names of a man who was 24, a boy who was 10 and a girl who was 4 years old, followed by "matado por los soldados" (murdered by the soldiers) brought home some of the brutality of the war.

I

also felt honoured to be able to support the Guatemalan people in their

struggle for justice. There was a genocidal war in Guatemala which lasted

36 years, left 200,000 dead and caused the displacement of 1.5 million.

83% of the victims were indigenous people, and 93% of the atrocities were

committed by the Guatemalan armed forces.¹ Two of Guatemala's ex-dictators

are now being prosecuted for crimes against humanity and genocide, along

with other officers from their military command. But human rights abuses

are still common in Guatemala, and members of human rights and social

organisations still receive death threats, including organisations involved

in the genocide cases.² The abuses are also linked to the greed of

big corporations, the actions of international financial institutions,

and so-called 'free' trade agreements. The war itself began after a dispute

between the United Fruit Company and the (then) democratic-socialist Guatemalan

government in 1953, who wanted to redistribute unused UFC land. The government

refused to pay the $15,854,849 compensation demanded by UFC (much more

than the land's real value), and so was overthrown in a US backed military

coup the next year. During the war, the World Bank lent money for the

construction of the Chixoy Dam, which displaced thousands of indigenous

Maya-Achi people from their sacred lands. They were unwilling to go, until

the death squads and army massacred 400 people - forcing the survivors

to flee. The filling of the dam basin began after the final massacre,

in January 1983.³

I

also felt honoured to be able to support the Guatemalan people in their

struggle for justice. There was a genocidal war in Guatemala which lasted

36 years, left 200,000 dead and caused the displacement of 1.5 million.

83% of the victims were indigenous people, and 93% of the atrocities were

committed by the Guatemalan armed forces.¹ Two of Guatemala's ex-dictators

are now being prosecuted for crimes against humanity and genocide, along

with other officers from their military command. But human rights abuses

are still common in Guatemala, and members of human rights and social

organisations still receive death threats, including organisations involved

in the genocide cases.² The abuses are also linked to the greed of

big corporations, the actions of international financial institutions,

and so-called 'free' trade agreements. The war itself began after a dispute

between the United Fruit Company and the (then) democratic-socialist Guatemalan

government in 1953, who wanted to redistribute unused UFC land. The government

refused to pay the $15,854,849 compensation demanded by UFC (much more

than the land's real value), and so was overthrown in a US backed military

coup the next year. During the war, the World Bank lent money for the

construction of the Chixoy Dam, which displaced thousands of indigenous

Maya-Achi people from their sacred lands. They were unwilling to go, until

the death squads and army massacred 400 people - forcing the survivors

to flee. The filling of the dam basin began after the final massacre,

in January 1983.³

Finally, the protests against the recently signed CAFTA (Central America Free Trade Agreement) have been met with repression and police violence. The agreement may lead to the bankrupting and loss of land of small farmers, since it removes the import taxes on cheap subsidised grain from the US. CAFTA will also undermine labour rights, help destroy the environment, delay the availability of cheap generic medicines and lead to increased privatisation. Two people were shot dead by police during the protests in March, another later died from his injuries and nine others suffered bullet wounds in Colotenango. In Guatemala City the 30,000 marchers were met by the police and army with '1980s style' tear gas and bullets.

This shows how human rights have been abused repeatedly in Guatemala to squash protests against the expansion of 'free' market capitalism. The fight against impunity must include the big corporations who profit from it, and from repressive governments around the world.

1 UN (1999) Comision de Esclarecimiento Historico (Commission for Historical

Clarification). The report concluded that genocide was committed in Guatemala

between 1981-83. See: www.justiceforgenocide.org/dejure.html

2. Amnesty International (2005) "Human Rights Activists Under Attack

in 2005". Report dated 9th March 2005. AI Index: AMR 34/011/2005.

See: web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGAMR340142005?open&of=ENG-GTM

3. Jaroslava Colajacomo and the Rio Negro Community (1999). "The

Chixoy dam case - Submission for Presentation at the Sao Paulo/Latin America

Hearings". International Rivers Network. See: www.irn.org/programs/latamerica/chixoy.subm.html