| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

New

Selected Poems

New

Selected Poems

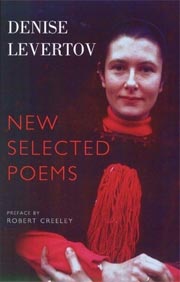

Denise Levertov - Bloodaxe Books

Reviewed by Adam Ford

If hearing the word 'poetry' conjures-up the image of red roses, blue violets and rhymes in your mind, then this poetry will certainly challenge that view. Apart from her earliest compositions, the poems read like a stream of consciousness, offering much more of an insight into the workings of Levertov mind than rhymes and rhythms ever could.

Levertov's "organic" style of writing was popularised by the poets of the 'Beat generation' in the early 1950s, but Levertov had used that technique long before it became common currency. Unlike many of the Beats - preoccupied as they were with the social movements of their time - Levertov's poetry has a timeless feel. She saw the poet as a spiritual voice - interpreting the divine eternal mysteries of the universe - rather than a mere lyrical reporter on society.

In the evocative Listening to Distant Guns - Levertov's first published poem - she describes walking through a park in Buckinghamshire during the Second World War. Contrasting the tranquil beauty of her surroundings with the remote gunfire and "battle scream" overseas, she expresses disbelief that two such different scenes can take place under the same sky. This poem - whilst structurally very different to her later work - establishes the central themes that would preoccupy her: nature, war, and love.

During the 1960s and 70s, Levertov was poetry editor for two activist magazines - Mother Jones and The Nation - and it was during this era that her poetry became more overtly political. In The Sorrow Dance, she speaks of murder and mutilation in Vietnam as an extension of the everyday struggle she found in society:

"We have breathed the grits of it in/ all our lives/ our lungs are pocked with it/ the mucous membrane of our dreams/ coated with it, the imagination/ filmed over with the gray filth of it".

New Selected Poems - replacing Bloodaxe's 1986 retrospective - includes many of Levertov's later works, written before her death at the age of seventy-four in 1997. These compositions - which caused shock amongst her political friends - reflected a conversion to the strict morality of Catholicism. In a sense, however, they are not so different from what had come before, expressing a spiritual connection between each individual, that goes beyond earthly conflict. In lines that provide a fitting memorial, she proclaims:

"when we give to each other the roses of our communion/ when we taste in small victories sometimes the small, ephemeral yet joyful/ harvest of our striving/ great power flows from us".

New Selected Poems may not rhyme, but it does give us a fascinating glimpse into a life worth celebrating. Anyone who was alive during the twentieth century should find something of themselves within its pages.