| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

The Long Shadow of War

By Dave Whyte

It is now a well-worn cliché that truth is the first casualty of war. This ‘war’ has certainly cast a long shadow over truth. The first casualty – long before the invasion commenced – was the justification for launching an attack in the first place.

The

claim that there were links between Saddam and Al Qaeda was so ridiculous

it was quietly forgotten. Weapons of mass destruction then became the

new official reason (Bush even foretold a mushroom cloud over Washington).

Blair’s cabinet fell for this fairytale hook line and sinker. Finally

we were fed excuse number three: that this is a war for the liberation

of Iraq and its people from an evil regime. Winston Smith, the main character

in George Orwell’s 1984 observed: ‘If all others accept the

lie the Party told – if all records told the same tale – then

the lie passed into history and became truth’. During this invasion,

truths have been discarded and reconstructed to match the imperatives

of US and UK governments with martial cynicism. They have been turned

inside out and wrapped around the dispatches of the embedded correspondents

in order to convince us of the humanitarian and libertarian aims of the

invasion.

The

claim that there were links between Saddam and Al Qaeda was so ridiculous

it was quietly forgotten. Weapons of mass destruction then became the

new official reason (Bush even foretold a mushroom cloud over Washington).

Blair’s cabinet fell for this fairytale hook line and sinker. Finally

we were fed excuse number three: that this is a war for the liberation

of Iraq and its people from an evil regime. Winston Smith, the main character

in George Orwell’s 1984 observed: ‘If all others accept the

lie the Party told – if all records told the same tale – then

the lie passed into history and became truth’. During this invasion,

truths have been discarded and reconstructed to match the imperatives

of US and UK governments with martial cynicism. They have been turned

inside out and wrapped around the dispatches of the embedded correspondents

in order to convince us of the humanitarian and libertarian aims of the

invasion.

In order to achieve this contortionism, our language is absorbing the euphemisms of the state military machine. It is a manoeuvre that Orwell’s Ministry of Truth would have been proud of. Last time around it was ‘collateral damage’ that scarred our consciousness. That old-time favourite, ‘friendly fire’ has been wheeled out again. Jack Straw revels in his new-found vocabulary, mimicking his Generals by describing a war zone where at least 13,000 people have been shot or blown up as ‘theatre’. For cluster bombs and landmines read ‘ordinance’. This language is anaesthetising, it provides a vocabulary for the translation of human suffering into military strategy. Sterile descriptive terms have become part of the media drone, repeated mantra-like by war correspondents. ‘Precision bombing’ is used without irony, as once again US missiles ended up hitting, never mind the wrong target, but on occasion the wrong country. The Iraqi forces that actually refused to surrender on request became widely known as ‘pockets of resistance’.

There

may be no Ministry of Truth here. The fact is, there is no need for a

Ministry of Truth. But there certainly is a regime of truth. On behalf

of their governments, the western mass media has loyally promoted a military

regime of truth, a regime with the remit to persuade us that 2 + 2 = 5.

This much is recognised by some dissenting elements within the press.

As New York Times columnist Paul Krugman points out: ‘my guess is

that most Americans believe that we have found [weapons of mass destruction].

Each potential find gets blaring coverage on TV; how many people catch

the later announcement – if it is ever announced – that it

was a false alarm? It’s a pattern of misinformation that recapitulates

the way the war was sold in the first place. Each administration charge

against Iraq received prominent coverage; the subsequent debunking did

not.’ One White House official has since claimed that the WMD claim

has indeed been a gross distortion. But ‘we were not lying’

– heaven forbid – ‘it was just a matter of emphasis.’

There

may be no Ministry of Truth here. The fact is, there is no need for a

Ministry of Truth. But there certainly is a regime of truth. On behalf

of their governments, the western mass media has loyally promoted a military

regime of truth, a regime with the remit to persuade us that 2 + 2 = 5.

This much is recognised by some dissenting elements within the press.

As New York Times columnist Paul Krugman points out: ‘my guess is

that most Americans believe that we have found [weapons of mass destruction].

Each potential find gets blaring coverage on TV; how many people catch

the later announcement – if it is ever announced – that it

was a false alarm? It’s a pattern of misinformation that recapitulates

the way the war was sold in the first place. Each administration charge

against Iraq received prominent coverage; the subsequent debunking did

not.’ One White House official has since claimed that the WMD claim

has indeed been a gross distortion. But ‘we were not lying’

– heaven forbid – ‘it was just a matter of emphasis.’

In the shadows, our news bulletins are still beamed across the world in a language infused with the imagery of emancipation. Popular uprisings against the invaders are played down, as are the regular shooting of those demonstrators by US troops; the real biological warfare (the disease and deadly bacterial infections caused by deliberate targeting of vital power and water supplies) has hardly been reported; when it is reported, it is blamed upon the ‘evil regime’. The one in four children on the point of starvation are ignored, while the crowds that meet the token aid deliveries jostle for position with the western world’s camera crews. There is a much more fundamental issue that remained ignored: was this really a war? We saw on our TV screens an invasion of one of the weakest states in the Middle East (in military terms) by the worlds only superpower. Hardly a ‘war’. We cannot be sure that one Iraqi fighter plane even left the ground. Roughly a hundred times as many Iraqi soldiers died as did US soldiers. Nonetheless, the vocabulary of war – the Newspeak of the 21st century – has spread like a virus through our media.

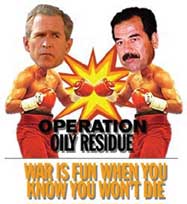

Perhaps

the least misleading term in the new vocabulary of war to rise to prominence

in this period has been the tag of ‘embedded journalist’.

It is a description that actually captures the essence of this invasion.

Of course the newshounds are embedded with the army. They have signed

contracts that say so. But this war has also revealed how solidly the

Bush administration is embedded in oil capital, and more generally how

embedded states are in markets. It has become crystal clear that the looting

of Iraq is the true motive behind this war. For it is not the Iraqi people,

but their commodities and markets that are being ‘emancipated’

on behalf of US and British capital. Under this regime of truth, freedom

= profit extraction; liberation = looting.

Perhaps

the least misleading term in the new vocabulary of war to rise to prominence

in this period has been the tag of ‘embedded journalist’.

It is a description that actually captures the essence of this invasion.

Of course the newshounds are embedded with the army. They have signed

contracts that say so. But this war has also revealed how solidly the

Bush administration is embedded in oil capital, and more generally how

embedded states are in markets. It has become crystal clear that the looting

of Iraq is the true motive behind this war. For it is not the Iraqi people,

but their commodities and markets that are being ‘emancipated’

on behalf of US and British capital. Under this regime of truth, freedom

= profit extraction; liberation = looting.

We know now that the corporate looters have been in Iraq since before the first missile was fired. It was reported that BP consultants were on hand to give military personnel advice and training on minimising losses of oil before US forces launched their mission to capture the oil fields. US corporation Halliburton sent in contractors with the troops. The same company had made a packet doing the same job in Kuwait in the 1991 Gulf war. The Halliburton subsidiary Kellogg Brown and Root (Vice President Dick Cheney’s company) is already rich on the back of a $300m contract with the US Navy, including a $35m+ contract to build the detention cells at Guantanamo Bay.

The total cost of rebuilding Iraq is likely to exceed $100b. The rebuilding of oil infrastructure (‘damaged infrastructure’ = structural devastation wrecked by 10 years of sanctions and bombing) alone is going to offer a bonanza worth $3b to construction firms. The so-called ‘coalition of the willing’ is quickly transforming into a ‘coalition of the desperate to make a fast buck’. British firm AMEC (of Illisu Dam fame) and US Fluor Corporation (who notoriously hired thugs in KKK outfits to beat up striking workers in South Africa) are teaming up to rebuild the infrastructure. Labour minister Patricia Hewitt pleaded with the US State Department for some crumbs off the table for British corporations while bombs still dropped on Iraqi children. It was an unspeakably obscene spectacle of gluttony.

But this invasion is not simply a product of an economy of convenience: ‘we bomb you to kingdom come and then you pay our companies to pick up the pieces’. Neither is it simply all for Iraq’s oil reserves. The Iraqi invasion had a much bigger aim: to challenge the ability of other oil producing countries to set the price of oil.

Although

it is likely that the US will keep Iraq as members of the oil cartel OPEC,

it is almost certain that US-controlled Iraq will invoke the right to

set its own price. This will not only undermine OPEC’s influence,

but will allow the US global domination over the price of oil. There are

other reasons for the war coming at this time. US military and foreign

policy is now overtly geared up to challenging the rising value of the

Euro as a world currency alternative to the dollar. Germany has been hoping

for sometime to open a new petroleum exchange that will trade oil in Euros.

France and Russia may have had a variety of reasons for opposing the war,

but one was surely that had the sanctions been lifted when Saddam was

still in power it would have made ‘live’ their oil agreements

with Iraq. Also important are the long-term strategic importance of securing

the state of Israel as the most stable US ally in the middle east, and

keeping a check on China’s ambitions for economic expansion. Europe

has emerged as major challenge to the hegemony of the petrodollar. There

may well be another challenge at some point in the future, led by China.

Although

it is likely that the US will keep Iraq as members of the oil cartel OPEC,

it is almost certain that US-controlled Iraq will invoke the right to

set its own price. This will not only undermine OPEC’s influence,

but will allow the US global domination over the price of oil. There are

other reasons for the war coming at this time. US military and foreign

policy is now overtly geared up to challenging the rising value of the

Euro as a world currency alternative to the dollar. Germany has been hoping

for sometime to open a new petroleum exchange that will trade oil in Euros.

France and Russia may have had a variety of reasons for opposing the war,

but one was surely that had the sanctions been lifted when Saddam was

still in power it would have made ‘live’ their oil agreements

with Iraq. Also important are the long-term strategic importance of securing

the state of Israel as the most stable US ally in the middle east, and

keeping a check on China’s ambitions for economic expansion. Europe

has emerged as major challenge to the hegemony of the petrodollar. There

may well be another challenge at some point in the future, led by China.

In Orwell’s book, the three powers (Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia) severed and reformed alliances, each time erasing the memory that the new enemy had ever been an ally. This is precisely what the US has done to its lesser enemies Saddam, Noriega, and Mobuto to name but three. Current US State Department proclamations on France and ‘old Europe’ suggest the possibility that truly powerful allies might also be transformed into enemies. George Orwell’s nightmare vision of the world may soon reveal close parallels to the future sought by George Bush. If this seems apocalyptic, we should remember that the attack on Iraq, given that it provoked the largest demonstrations against war in history, revealed the vulnerability of our leaders’ regime of truth. The huge majority of people across the globe didn’t believe a word of it. If we can capitalise on this massive opposition to US military hegemony, the chances of building alternatives to the new world order are now greater than ever before. If anything about our future is certain, we are not, and never will be, the wholly docile and acquiescent population described in 1984.