| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Back to index of Nerve 14 - Summer 2009

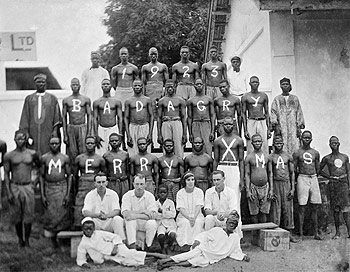

One

of the most striking exhibits in Liverpool’s new International Slavery

Museum is this photograph, taken in colonial Nigeria. Britain –

having decided it was no longer profitable to save millions of Africans

from their savage ignorance by forcibly transporting them to the New World

on ships powered by wind, waves and working class sailors – sent

some of her finest sons and daughters to do the civilising on African

soil.

One

of the most striking exhibits in Liverpool’s new International Slavery

Museum is this photograph, taken in colonial Nigeria. Britain –

having decided it was no longer profitable to save millions of Africans

from their savage ignorance by forcibly transporting them to the New World

on ships powered by wind, waves and working class sailors – sent

some of her finest sons and daughters to do the civilising on African

soil.

A Christian Greeting to the Former Capital of Culture

By Tayo Aluko

My forebears were apparently so grateful that they allowed the colonialists to take fair payment for their efforts in the form of gold, diamonds, rubber, palm oil and countless other natural resources. By some inexplicable carelessness during the planet’s creation, this had all wound up on the wrong continent. To further demonstrate their gratitude, the Badagry gentlemen lent their dark torsos to their masters to send that joyful Christian message home.

It is fitting that Slavery Remembrance Day of 2007 - the bicentenary year of the Slavery Abolition Act - was chosen as the museum’s opening day. It was another first for Liverpool: she was the first city to officially commemorate this anniversary of the 23rd August 1791 outbreak of the successful slave revolt in St. Domingo (now Haiti) led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, and first in the world to make an official apology for its role in the slave trade, committing itself to action to celebrate the skills and talents of all its people, regardless of race.

Dr. Mark Christian, a Liverpool-born Black academic, recently gave a lecture at the ISM titled “The Age of Slave Apologies”, in which he examined Liverpool’s case. Accepting that Liverpool’s crimes had been rightly acknowledged and remorse expressed, where, he wondered, was the evidence that Liverpool’s Black people are no longer marginalized and oppressed in their city? Christian had been away ten years, but found little evidence of improvement in his brethren’s lot: he still couldn’t see that many Black people working in the city centre; the area of Liverpool 8 in which he grew up is a ghost town, as the council has been preparing it for “redevelopment” for almost twenty years since the Toxteth riots.

Christian studied and eventually taught at the Charles Wootton Centre for Further Education, set up in the 1970s by Blacks for Blacks, and named after the victim of a 1919 racist killing. It closed in 2000 (the year after the Council’s apology), having lost Council support, and the lack of employment opportunities in Liverpool and indeed England forced him to take up a lectureship in an American university. In his lecture, he recalled the day in 1985 when, stepping out of “The Charlie” to get some lunch, he found himself being approached by Michael Heseltine and a bevy of reporters, and later seeing himself on TV that evening, having unwittingly presented “Tarzan” with a great photo opportunity to show how his government was determined to do something for those poor Blacks in the Toxteth Jungle.

Heseltine and his successors would have been interested in the suggested 10-point plan with which Christian closed his lecture. The plan includes education scholarships to Liverpool’s Universities, special internships in politics, media, banking and business organisations, affordable housing and the construction of a Black Institute for Social, Economic and Cultural Research.

Downtown, over lunch at the prestigious Athenaeum (where I was one of two black proprietors), Christian bemoans the fact that his beloved Charlie is now being developed into “luxury apartments” and wonders how many local Blacks will be able to obtain mortgages in the current climate. I described my efforts to develop affordable eco-friendly accommodation nearby, which sadly failed for want of council subsidy, and how the Council appeared happy to see me sell the site – undeveloped - to developers from Manchester (of all places!). Then there was the case of my being gazumped by Cosmopolitan Housing Association on another site which I offered them in naïvely misplaced good faith, thinking they would be interested in collaborating on a green scheme.

As the memory of her tenure as European Capital of Culture melts slowly away like the polar ice caps, nobody can accuse Liverpool of tokenism by using 2008 to present one black developer as evidence to the world of our integration at all levels of society. Still, at the end of this, the City’s Year for the Environment, it will be interesting to see what buildings they put forward as examples of good green practice.

They may receive a Christian greeting from one of their finest sons in America, reminding them of their apology and promises, suggesting they support the construction of an Ecological Study Centre and a Black Studies Centre, and that they use a Black architect. They’ll probably find one in Manchester or London. No need to worry about how much oil they’ll burn travelling up: it comes cheaply enough from Nigeria’s Delta Region: quite near Badagry, as the culture vulture flies.

Right, I’m off to put some money into a research project into nuclear-powered car engines. The white man says the future is nuclear…

Tayo Aluko trained as an architect in Liverpool. He is also the writer and performer of the award-winning play, Call Mr Robeson: www.callmrrobeson.com