| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Back to index of Nerve 11 - Winter 2007

Seeds of Hope:

From DIY disarmament to tackling climate change...

Seeds of Hope:

From DIY disarmament to tackling climate change...

By Jo Blackman

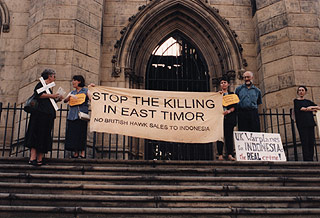

29 January 1996, 3am, British Aerospace Warton… Lotta, Andrea and I share a moment of silent reflection and a hug, before cutting a hole in the perimeter fence, slipping through, hurrying across a flood-lit verge towards a huge hangar, levering open a door and disarming Hawk jet ZH955. This ground-attack plane was due to be delivered to the Indonesian military dictatorship within weeks or even days and would likely have been used to bomb people in occupied East Timor. After hammering on the jet's nose, wings and control panel, we scattered photos of Timorese children, hung banners and placed film footage from East Timor in the cockpit to explain our action. When the security guards and police finally turned up (only after we had phoned the press from the hangar!), we were charged with criminal damage - totalling £1.5 million - and conspiracy, and remanded to Risley Prison to await trial. Angie - the fourth member of our group - was arrested a week later after publicly inviting others to join her in continuing the disarmament work.

Our action was in the tradition of the Ploughshares movement, in which people take personal responsibility for the disarmament of weapons. Ploughshares actions are non-violent and accountable and usually involve significant preparation time: (together with our support group, we planned, researched and role-played over 10 months). Our trial took place in July 1996 at Liverpool Crown Court. Each day, supporters processed from St Luke's Church to join the vigil outside court. Inside the courtroom, we presented our case - that we were using "reasonable force in the prevention of crime", as is allowed in English law. We called witnesses - including Jose Ramos Horta (now president of East Timor) who testified to the use of Hawks against the Timorese population. After much suspense, the jury found us "not guilty" on all charges - an unprecedented and courageous verdict. Since then, juries have acquitted people for attempting to disarm weapon systems such as Trident and B52 bombers destined for use in Iraq.

For me personally, the last 11 years have been a roller-coaster - struggling with burn-out and single parenthood, taking my son to visit his father in East Timor and most recently, working to raise awareness of climate change. I had been in blissful denial about the reality of climate change until May 2005, when I attended a workshop led by Joanna Macy . And then it sunk in - we are the last generations that can make the necessary transition from our industrial growth society to a life-sustaining civilization. Since then, I've alternated between shock and anger as I have begun to understand the extent of the human and environmental catastrophe facing us, and our part in creating this monster.

Climate change poses as grave a threat to the people of East Timor as the Indonesian occupation ever did. Over the 24 years of the occupation, the military raped, tortured and murdered the people of East Timor, displacing thousands into "resettlement villages" with restricted access to their land and food supply. A staggering one-third of the population died as a result of this genocide. I fear that an even greater number of Timorese will lose their lives over the next couple of decades, as a result of catastrophic climate change - rising sea levels (a large proportion of the population live at sea level), hurricanes, drought and associated forest fires and crop failure, spread of malaria to higher altitudes…

When I first learnt about Indonesia's brutal occupation of East Timor, I was particularly angry that British companies were selling arms to Indonesia with government approval and encouragement. It was this sense of direct connection and responsibility that inspired me to take action. Likewise there is a direct and frightening connection between our consumer society and accelerating climate chaos. In Britain, our carbon footprints grossly exceed those of most of the world's population. The people of Chad and Afghanistan survive for a year on the amount of energy that we burn in just one day. Although there is much hype about the rapidly increasing carbon emissions in India and China, our average of 13 tonnes per person (including aviation) is still ten times India's average emissions and more than double China's. The people of island nations and low-lying coastal regions such as East Timor, Tuvalu and Bangladesh, and vast swathes of drought-prone central Africa, are paying now and will continue to pay for our society's addiction to an extravagant degree of comfort and convenience - for our resistance to giving up things which we assume as a birthright but which most people in the world can never have access to. Ultimately the survival of human culture itself is in jeopardy.

I frequently feel overwhelmed by the scale of the task ahead of us… There is an emerging consensus that to avoid the devastation of human and other species, we need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 90% in the next 10 - 20 years (perhaps much sooner ). Then in June this year, six scientists from leading scientific institutions warned that: "The Earth today stands in imminent peril ...and nothing short of a planetary rescue will save it from the environmental cataclysm of dangerous climate change".

In 1996 when we were coming up to trial, the odds seemed stacked against us. Our case had been assigned to the local "hanging" judge and even our keenest supporters were assuming we'd be convicted and do our time. And then we decided to start talking affirmatively about acquittal, acting as if we lived in a world where it was ordinary and natural for juries to condemn arms dealers and celebrate acts of disarmament. My despondency shifted and suddenly it seemed realistic to invite the jury to acquit us.

Our urgent task now is to create positive visions of a post-carbon future and start living them! We need to nurture a belief within the public consciousness that we can live happy and fulfilling lives within a fair and sustainable share of the earth's resources. (For almost all of us in Britain, this means such a far-reaching reduction in our material affluence that it is difficult to imagine.) Recently I've found renewed hope from initiatives such as the Transition Towns movement - in which communities develop collective visions of a sustainable post-carbon future, devise "energy descent plans" (how to make the transition) and act together on these plans. This approach isn't based on simply hoping for governments, the UN, corporations or experts to pull off a rescue package, but is founded on an understanding of our collective power to transform our society. Let's use it.