| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Back to index of Nerve 10 - Spring 2007

Gonz

Away on Business

Gonz

Away on Business

By John Maher

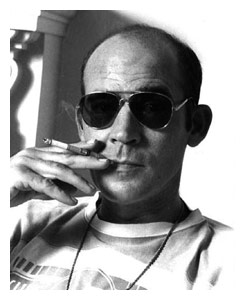

As if to prove his eccentricities, Hunter S. Thompson requested that his ashes be blasted from a cannon atop a 150 foot tower. The pioneer and all-round 'madman' passed away back in February 2005 leaving a mammoth mark on the very form of written journalism.

Thompson was responsible for developing a fast-paced, drugged-up, vociferous narrative style, that would come to characterise his work: Gonzo. Hailing from Kentucky, he began writing in the late fifties, originally as a news and sports hack, but was regularly sacked from positions - including one at Time magazine - for being unruly. It was not until the seventies that he gained notoriety. The Gonzo term itself stuck after fellow reporter Bill Cardoso read an early Hunter piece, and excited by its tenacity and style, roared (in Irish slang) 'It's pure Gonzo!'

Yet Thompson's ethic was formed in the decade before he came to prominence. The New York writers of the 1960s - such as Tom Wolfe - eschewed the notion that reportage must not be angled from the writer's personal perspective, and moreover began to integrate fictitious elements into articles. This movement is well documented by Wolfe and Ed Johnson in the lengthy tome, The New Journalism. Along with the LSD-fuelled vitality of the beat auteur, such as Kerouac (of which his largely unedited On the Road is the cornerstone), it was through these trends that Gonzo came to fruition.

Perhaps the greatest work which embodies all tenets of this stylistic mode is Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72, where Thompson rigorously followed the race for the American Democratic nomination over 13 gruelling months. Originally serialised in Rolling Stone and later published as a single document, the pages are littered with the writer's personal interchanges with the candidates, memory-removed hazy parties, hopelessly dire hotel rooms, stream-of-consciousness rambling and insider gossip, with Thompson himself a central character to the plot. The best bit is a set piece aboard the 'sunshine special' train when candidate Ed Muskie is cajoled by a 'boohoo', whom Thompson had given his press badge to the night before. Aimed as an attempt to ratchet support in a controlled environment by the politician, the trip ends in disaster for Muskie.

Thompson is embedded - in the sense of today's journos in Iraq and Afghanistan

- but without the pressure to report completely from one side, venting

his ire from the frontline, so close you can smell the sweat of the ruffled

politicians. Campaign Trail took on a fantastical element, more akin to

science fiction at times than journalism, with reality indecipherable

from narcotics-induced visions and the depths of his imagination: narrative

set-pieces were the call of the day, another feature developed from the

New Journalists. To further amplify the sense of chaos, Thompson sent

many pages to press direct from his notebook, as deadline time ran out.

Here's a sense of the fluidity of the work, taken from early on:

We seem to have wandered off again, and this time I can't afford the luxury of raving at great length about anything that slides into my head. So, rather than miss another deadline, I want to zip up the nut with a fast and extremely pithy 500 words…because that's all the space available, and in two hours I have to lash my rum-soaked red convertible across the Rickenbacker Causeway.

In an attempt to emulate his hero, Jazz-age writer F. Scott Fitzgerald,

chapters began with sinuous, romantic, descriptive prose, where Thompson

would create vivid scenes from which he himself was inextricable.

Gonzo was important because it began to erode a previously entrenched

form of journalism that was stuffy, conformist, homogeneous and without

fire. What Thompson tried to prove was that journalism could be both subjective

and insightful, in turn dispelling the myth of completely objective writing,

where no hidden personal feeling would creep in. He infused a little individuality

into the pages, a little flair and passion. For him, the world wasn't

as straight-laced as factual reporting would have you believe. Life was

grimy: drugs existed. Throughout Fear and Loathing… he is also immensely

critical of the false, stage-managed artificiality of the mainstream media,

and how politicians manipulate the camera.

Sure, there's loads of direct opinion from Thompson, which borders on diatribe (Nixon is a 'Born Loser', and 'there's no avoiding Hubert Humphrey in Wisconsin this week. The bastard is everywhere'), but he doesn't try to cloud it or disguise his feelings as something they aren't. He gives the facts as well: vote counts in statistical form can't be altered by fiction.

So what of Thompson's idiosyncratic writing legacy? Today's news market is owned by a small number of dominant corporations, such as Murdoch's News Corp and Trinity Mirror. With stories heavily dependent on PR and news agencies, what with constant outsourcing by newspapers in a bid to halt falling revenue, it is more difficult now than ever for singular personality writers to get employed, let alone noticed. What we're being left with, in the main, is a bland, emotionless text which reads the same across the oligopoly. As the current US candidacy race gathers momentum, it's a worrying reality.

Recently I watched Democratic Whizz-kid Barack Obama being tracked by a hoard of BBC cameras and Washington correspondent Matt Frei on a voter spree in Illinois. It's difficult to envisage Frei getting loaded at the afterparty and telling of how the walls began to cave in about 3am when he started talking football with Obama high on opium and downing another rum 'n' coke. Ok, I'm being a bit tongue in cheek here, there's no room for this on TV - and Frei is one of the best - but you see what I'm getting at. Chris Dahlen on Pitchfork argues that today's journalists simply don't know how to interpret the modern world and all its technologies: no one is head and shoulders above the chasing pack.

Thompson's impact on both literature and journalism is unquestionable. But somewhere there must be a few to liven up the political and democratic debate, to destabilise the current sanitised prose that is all too popular. Who will be there at the polls to capture the uncertainty? Who will ruffle a few feathers? Set your cannons, for now all we need are some new renegades.