| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

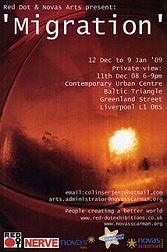

Migration

Migration

Red Dot Exhibitions

Contemporary Urban Centre, Greenland Street

12th December 2008 - 9th January 2009

Review of Migration by Adam Ford

Red Dot have chosen migration as the theme for their latest group show. This proved to be a wise choice, for it produces an exhibition which gives a sense of the complex and almost contradictory nature of the subject. The timelessness and the transitory nature of the phenomenon are explored, alongside its universality, and yet the hatred and division often associated with it also gets a look in.

Artwork by migrants from many different areas (Romania, Afghanistan, Tibet) is displayed, plus creations from Red Dot regulars who - though born in this country - are of course descended from migrants somewhere down the line.

But the birds soar far above all this human confusion, making annual journeys around the world to find the most favourable conditions, and attracting no resentment from people who are used to passport control. Barbara Jones depicts this in her ‘Paper‘, with her hundreds of origami birds and boats.

Carl Fletcher and Ken Bullock’s ‘The Migration of Music’ celebrates music’s existence as a global language that crosses many barriers, with their collage of album covers in the shape of a boat crossing water.

Nicole Bartos’ ‘Linking Space to Channel Love and Warm Hearts’ is a reminded what migrants leave behind when forced to find a new home by poor conditions in their country of origin. Her collage of airmail letters - one mysteriously singed - exactly lives up to her description, and is a touching display of emotions we all share, but are often kept secret.

‘My Mother’s Mother’s Mother’ by Alice Lenkiewicz stretches back through history to her Welsh great-grandmother, in a series of three mirrors decorated with floral designs and family photographs. Again here, the viewer experiences something that unites us all. The clothes and locations are different of course, but almost everyone has family photographs, and fond memories of relatives.

On the other side of things, a John O’Neill piece a shows the challenges awaiting more recent Polish arrivals to Britain. As three men stride out the back of a van, three more sit grim-faced on a wall that bears the words ‘Immigrant scum’ and ‘Polish out’. Clearly, the indigenous trio see the newcomers as rivals.

Migration has been around since bacteria evolved with flagella to propel themselves, but it is still a painful process in many respects. Red Dot’s exhibition has captured that.

Review of Migration by Sandra Gibson

'Artists from Red Dot will be interpreting through their artwork the many concepts and themes of the term migration.'

Migration is a hot topic - it’s a big issue - a global phenomenon that has been creatively and widely examined in several recent Liverpool exhibitions. Hawkins and Co. concentrated on the historical aspects of world trade and the diaspora of Africans to America and the Caribbean as well as its continuing effects. Port City looked at present migration and the anxious border experiences of the migrant. Fis 2008 addressed the links between Liverpool and Ireland.

The Migration exhibition at CUC is contemporary - with some historical echoes - but it also extends the thematic arena and is less political than the aforementioned. Yes, we have the Tibetan diaspora but we also have the global dissemination of music. We have the brutality of displacement in a hostile modern city but we also have the pioneering joy of the traveller and the single-pointed endeavour of migrating birds.

Asserting that ‘Music is the greatest migrant’ Carl Fletcher and Ken Bullock’s celebratory sailing ship ‘The Migration of Music – by Starving Dogs’ pleases by its humour and its reference to the musically iconic. Ringo Starr appears to have been cast adrift - as well he might - and I like the way the seascape is extended round the canvas edges.

Eimear Kavanagh’s work is similarly celebratory - portraying Northern India with its pinewoods and agricultural villages and the presence of Tibetan cultural images. The prayer flag is a powerful symbol of the Tibetan diaspora post 1949, operating on two levels. Their presence alongside Indian culture is proof of Tibetan migration, settlement and acceptance. On a spiritual level, the flags - with their ancient Buddhist prayers, mantras and symbols - are offerings to the world, distributed every time the wind blows them. Kavanagh’s paintings are imbued with a sense of spiritual beauty conveying a real impression of the wild mountain terrain traversed by Tibetan refugees and the textured richness of both cultures.

Tenzin Yonten has emphasised the resilience of his Buddhist inheritance by exhibiting two thangkas, one traditionally painted as found in Tibet or India, the other showing a Buddha against a backdrop of Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral and Liver Building, both paintings nevertheless retaining the traditional iconography and symbolism: lotus flower, peacock and conch.

Using a more abstract approach, Sarah Nicholson’s installation using kitchen rolls echoes the prayer flag image and demonstrates the osmotic nature of migratory culture whilst at the same time using complementary colours to note harmonious distinction.

Several works address the epic journey made by the migrant. Jane Fairhurst’s installation ‘Over the Water’ emphasises the commonality of the experience by using the same blue plastic material for each figure and each sailing vessel whilst retaining individual distinctions in each.

Adele Spiers’ apparently conventional seascape reveals a texture of small individual ripples.

Louise Waller has somewhat abstracted the idea of movement in her elegant diamond-shaped vehicular sculptures which cast shadows on the plinths. The diamond is an effective shape for conveying both the diminishment of leaving and the pioneering dynamic of forward moving.

The shape of movement is similarly addressed by Barbara Jones who has used origami to fashion birds and boats and planes from recycled paper bearing the details of ship registry - the medium becoming part of the message.

Susan Meyerhoff Sharples’ copper sculpture ‘Vol’ is an effective celebration of flight and aspiration from a substantial foundation – a rhythmic combination of the abstract and natural form.

Sue Milburn’s photographs and paintings emphasise the intimidation and exhilaration of the surging spaciousness of the journey. The imagery of tide and shore – journey and journey’s end – also invites the question: and what now?

A work by Michelle Hird comprises a faded map of the world and an aerial perspective of birds references the questing vigour of the instinct to migrate - immense distance being no obstacle – at the same time that it evokes, through the use of black silhouettes, a tabloid sense of predatory settlement.

Nathan Pendlebury’s series of eight paintings has a Miro-like quality of near abstraction. Collectively they convey the optimism of precision; they are occupied with the process of navigation and reference such issues as horizon, direction, the possibility of clement or inclement weather and notational accuracy.

Richard Ashworth’s series ‘Journey’ - which displays holes punched into canvas - offers two ideas. Firstly it’s the notion of breaking through one’s fear, the fear of others, the many obstacles to a new place. Secondly – and I think this is the stronger impression – it brings to mind the soulless bureaucracy of travel, of having ones papers in order, of having ones papers endlessly inspected, of having ones tickets punched to validate them…

The emotional effects of exile are also portrayed. At one end of the spectrum we have the eclectic instincts of the traveller to experience and retain and document their temporary expatriation. Alison Bailey Smith’s embroidered collages – her voyages stitched into place, her stamps and photos and artefacts of travel fixed and decoratively edged – raise the question of memory and the evocative power of the object to resurrect experiences whilst at the same time pointing out the irony of attempting to fix something that is essentially transitory.

The work of Nicola Bartos is imbued with a greater poignancy. It contains the yearning of the exile and also deals with the issue of memory. Her aide memoires: fragments of photograph, pottery, Romanian stamps, faded flowers, envelopes… are accentuated by the use of pins which not only give rise to the idea of pinning things down in memory but also evoke pain - each pin producing its own shadow. There’s the paranoia of flight and discovery in her use of shredded documents too. But the factor that reinforces the poignancy is the use of wax in these mixed media works. It has domestic and ecclesiastical connotations; it can embed and conceal and reveal objects but is also a medium easily changed by circumstances. Objects, the means of communication, people, societies - all can easily melt away in reality as well as in memory.

Alice Lenkiewicz has presented another facet of the theme of migration. Her installation of photographs on mirrors decorated in the folk art tradition has displayed the previous generations of her family whilst at the same time reflecting back the larger image of artist as observer as well as the exhibition goer as observer. In looking at her predecessors the artist is looking back in time and place and culture at the same time as she is looking at her own genetic links, the way the genetic code migrates from generation to generation, from country to country. In another installation, ‘Ivy’, the artist surprises the observer on a number of levels. A doll’s house has been aged and made rather gloomy by the use of dull greens and actual ivy – a swiftly colonising plant that cooperates with time to swamp buildings and render them spooky and hidden. Yet there are signs of homeliness – heart shapes carved out of the shutters and a light on the upper floor. This impression is rather short-lived because the occupant of the bedroom is a Pharaoh in his sarcophagus!

You can never be sure what you might find when you go back; you can never predict how time and memory will change things – not just buildings but also cultures.

At the other end of the emotional spectrum, John O’Neill has powerfully expressed the experience of the contemporary urban immigrant in three vigorously executed drawings. The use of colour in the smallest of the three is reminiscent of Munch’s portrayal of nauseous fear. The ubiquitous trucks, the graffiti [‘Immigrant scum’], the grotesque faces of the locals, the whole atmosphere of menace and cruelty provides an uncompromising view of how negative the immigrant experience can be. The drawing of the overbearingly powerful and oppressive urban environment and its adversarial inhabitants is equally arresting and disturbing. The third drawing shows a woman in Asian dress tending an urban garden. The vigour of multifarious growth is as strongly rendered as the aggression in the other two works and perhaps this emphatic image of tranquil potential for harmony is offered as a balancing energy. In other works the immigrant experience is perceived as perhaps less confrontational, more subtle, but nevertheless as uneasy and apprehensive.

Adele Spiers’ landscapes are a case in point. In one the orderly vegetation is threatened by a potentially tumultuous mountain. Perhaps this is also a reference to the environmental factors that give rise to the plight and subsequent flight of the migrant but the painting also works on the less literal level of conveying an emotion - as does the more explicit cloudscape with prison bars.

There are other works in the exhibition that work predominantly on this emotional - as opposed to narrative - level to explore the theme of migration. The photographs of Colin Serjent tend towards the abstract. They are ‘found’ images whose ambivalence enriches the experience. What could be a pile of domestic rubble could also be a larger landscape; what looks like a multi-layered frottage could also be the night sky threatened and rent asunder by a predatory aircraft over a desert. And all are beautiful in texture and detail and colour harmony yet the artist has conveyed a feeling of unease in the sense that things are not what they seem. How beautifully rich and red is the earth but how our attitude changes when we perceive what might be blood on the bits of cloth strewn around. We are made to experience the insecurity of perception that afflicts anyone unsure of their ground.

On the other hand, Christine O’Reilly Wilson’s paintings reflect a sense of youthful security - the rejuvenating optimism of the journey to a new life. ‘Yellow Belly Custard’ recreates her childhood, living near Cammell Laird where the ships destined for exotic journeys were built. This banner of celebration in sunshine yellow and complementary blues is a hymn to the hopeful emigrants who set sail for Australia after the War and more specifically to her friend who went in such a locally built ship. As the title indicates it’s also a celebration of childhood. ‘El Dorado’ similarly depicts a state of mind that is full of confidence in a new and exotic life.

Finally: some contrasts. Georgina Ravenscroft’s ‘Three Studies for Another Time and Another Place’ stress the possibilities for a global experience - irrespective of place and culture - presented by the computer age. This has obvious repercussions in terms of the cultural melting pot idea and paradoxically, the lessening of variety. Not everyone is happy with this, believing that differences should be respected. But this is what is happening.

Samiullah Nawzady’s ‘Afghan Way of Life’ draws attention to the limitations in the life of an Afghan woman serves to balance this reservation. The beautifully textured and brightly coloured richness of the piece certainly reflects the uniqueness of the culture but at the same time it targets the drudgery from which she has little opportunity to migrate, either in body or in mind.

Two other abstract paintings by Wendy Williams resemble seams of marbled rock, their monumental geological silence serving as an antidote to the human aspiration and restless suffering here represented.

My thanks to Colin Serjent for arranging this out-of-hours viewing and the supportive enthusiasm and patience of Art Officers at CUC Carla Weaver and Erin Threadgill.