| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Ellen

Gallagher

Ellen

Gallagher

Tate Liverpool

21st April – 27th August 2007

Reviewed by Jennie Lewis

Born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1965, Ellen Gallagher has, for years, followed her appreciation of art, developed her skill and become one of the most celebrated contemporary painters in the Western World. Having studied at Oberlin College, Ohio; The School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Skowhegan School of Art, Maine; she has polished her craft to the highest degree, and has produced some awe-inspiring work.

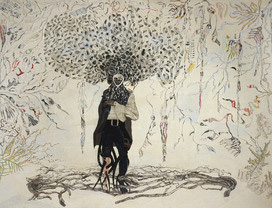

Her current exhibition at the Liverpool Tate indeed showcases her recent works, and charts her ongoing exploration of the Drexciya Mythos and the Black Atlantis. The idea stems from the suggestion that amphibian descendents of African women and children inhabit the seas between Africa and the Americas, after many jumped overboard and plummeted to their deaths during the gruelling journey of the middle passage, rather than be sold as slaves in America. Gallagher’s interpretation of the amphibious creatures becomes the narrative of her work for this exhibition, and she presents the haunting images by many different means. This disconcerting tale has very much influenced her recent works, making them as haunting as they are beautiful.

The focal point of the exhibition, ‘Bird in Hand’ sees the most ambitious artistry of the Watery Ecstatic series, execute through careful use of oil, ink, cut paper, polymer medium, salt and gold leaf on canvas. The results are exceptional on an aesthetic level, and succeed in adding depth and meaning to the narrative and premise behind its creation. Gallagher effectively evokes the sea, and reveals the isolation and desperation of African slaves through a carefully crafted absence of companionship.

Gallagher’s work is both visually pleasing and provocative of thought. What the images first appear, they are usually not, each requiring close inspection and careful contemplation. The diversity of applied technique to her artwork allows for some conflict within each piece, and empowers Gallagher to highlight focal points. However, she rarely does so by dramatic means, it is usually rather through implementation of subtle suggestion. There are two pieces in the exhibition consisting solely of words arranged around a jagged, spherical, almost map-like shape. The words are uncoloured and unmarked, simply cut paper against the stark white background. The lettering is large and usually in upper case, but one word ‘humania’, appears in the opposite. Remarkably, the potentially unnoticed inclusion of this word allows for the delivery of a poignant and powerful message, and suggests the inhumane treatment of African slaves.

The exhibition is, at first glance perhaps, dull and uninteresting, as rows of paintings guide you endlessly from door to door. My advice to anyone, though, would be to overlook initial impressions, as closer inspection of Gallagher’s work unlocks a hidden world of fantastical element, and dreamlike premise.