| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

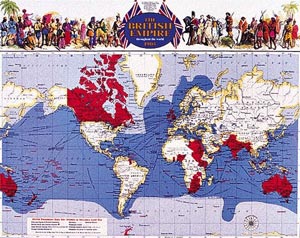

The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (Part 1)

By E. Hughes

The

British Empire was the first genuinely global empire, an empire that ranged,

at times, from the American colonies in the West, Australia and New Zealand

in the East, Canada and her dominions in the North and huge chunks of

Africa in the South, including Egypt and Rhodesia. These huge landmasses,

and many other smaller islands and places besides, were to be shaped,

controlled, dominated and otherwise brought under the dominion of a nation

which, prior to colonial ambitions, was a small and perhaps dull and uninspiring

set of countries. That the British Empire significantly kick-started the

world into the modern era, and gave the world a unifying language is not

really in dispute; but the truth behind the image certainly is, and the

ugly reality behind the ever-polished and very-rarely challenged veneer

of respectability the British, and hence the British Empire, in some quarters

have tried to maintain.

The

British Empire was the first genuinely global empire, an empire that ranged,

at times, from the American colonies in the West, Australia and New Zealand

in the East, Canada and her dominions in the North and huge chunks of

Africa in the South, including Egypt and Rhodesia. These huge landmasses,

and many other smaller islands and places besides, were to be shaped,

controlled, dominated and otherwise brought under the dominion of a nation

which, prior to colonial ambitions, was a small and perhaps dull and uninspiring

set of countries. That the British Empire significantly kick-started the

world into the modern era, and gave the world a unifying language is not

really in dispute; but the truth behind the image certainly is, and the

ugly reality behind the ever-polished and very-rarely challenged veneer

of respectability the British, and hence the British Empire, in some quarters

have tried to maintain.

Where do we begin? At the beginning. Far from Britain being historically a never-ending line of tyrants and wayward rulers, Britain has been, to some degree at any rate, a parliamentary democracy that reigned in kings and queens and rulers, and was the first to have a popular revolution, under Cromwell, in Europe. The Englishmen who started the first serious forays into venture capitalism, were little more than pirates and adventurers who plundered the Spanish main, and wanted a slice of the wealth flowing out of the New World, of which ventures were often backed by Royal decree. Here begins the roots of the British Empire.

From ideas of empire rose the ideas of capitalism, free trade, enforced labour, rigid hierarchies, the criminalisation of the poor, and severe and almost unquestioned divides between those who had and those who did not have, both at home and abroad. That this process made many people seriously wealthy cannot be disproved, that it also made many many more people far worse off is, in reality, more important an issue to deal with.

That the legacies of empire are far reaching can be seen only too clearly in places like Ireland, Africa, India and much of the Middle East at this present time. It is when racism and prejudice are broached, that the Empire seems to come into its own; Ireland was the first serious attempt by the British Crown and Parliament, to begin a process of English colonisation, whose colonists would then take over the ‘wilderness’ of Ireland and use the land more profitably. The Irish were treated like the native ‘Indians’ a little later in America, as being ‘in the way’, nomads who were uncivilised, and, more importantly, who did not utilise, and particularly, did not ‘own’ the land they wandered. This is an important point to understand, and much rests on this ‘belief’, both in Ireland, America and much later Africa and other nations. The inference being, in English and British mindsets, that because nobody ‘owned’ the land, it was up for grabs. A simple point, but much laboured, and was the intellectual argument for such colonialism. The Englishman was a gentleman, the Irishman, and henceforth many other nationalities, was an uncivilised and uncultured brute. This ‘excuse’, compounded with other often faulty reasoning and intellectualising, was the reason why Englishmen sought to establish colonies that would make them enormous profits, buy themselves into the gentry, win fame and glory, and establish their names. Such ideas of civilisation and ‘gentlemanliness’ being used to excuse ethnic cleansing, land grabbing, slavery and untold injustices have their reflections in most if not all empires, and are seen clearest in the ‘nazification’ of early 20th century Germany; when notions of superior and inferior excused the most barbarous and evil of practises.

Africa only really became a serious issue to the Empire at the end of the 19th century, but for centuries prior to this, was a source of wealth for Britain and Europe, primarily because of the slave trade, but also as a market for European goods, and as another outpost of European colonialism from the early 1600’s. According to Iggy Kim and Peter Boyle, in their article How the rich invented racism, racism has its historical roots in the development of capitalism. Slaves could be purchased cheaply and brought in unlimited numbers from Africa. In the racist mode of reasoning, the next logical step was to conclude that, somehow, blacks must have been "naturally" inferior to whites. Two other factors assisted the advance of racist ideas in the 19th century: the expansion of European capitalism to include huge colonial empires in Asia and Africa, and the development of early theories of human evolution. Gross manipulation of the latter helped justify the new global oppressive relations of imperialism.

Ports like Liverpool, Bristol, Cardiff and Glasgow, amongst no doubt many others, grew rich and powerful as a result of this trade, allowing merchants to expand, bankers to grow wealthy, companies to prosper, and many individuals to make more money than they knew what to do with; it was indeed a profitable trade, and also, more and more, a trade that is hidden from history. It is no exaggeration to say that the slave trade, and the profits it created, helped cement the emergence of Capitalism, Britain’s pre-eminence as a world empire, the beginnings of Britain’s industrialisation, and the creation of a class of capitalists with untold wealth and power at their fingertips. Such unequal relations of wealth and power, creating vast divisions in Britain and around the world, would become uncomfortable realities for many people, and sooner or later would be justified or explained away in high-blown intellectual and scientific terms.

Desmond Kuah, of the National University of Singapore, writes that by the middle of the nineteenth century, the British Empire was the largest and richest empire in the world. This naturally gave rise to the belief that the British themselves were the chosen race chosen to bring the benefits of western civilization to the backward areas of the world. With India’s conquest, in ways militarily, economic, social, ethnic and even religious, came then, as with other dominions, justifications and intellectual reasoning about British, and White European, ‘natural’ superiority and the ‘natural’ inferiority of conquered people’s around the world.

In understanding and accepting the real reasons for Empire, then a better understanding can be made of seeing the inherent divisions within the imperial system, and how racist and classist propaganda, to name but two, was heaped on top of centuries of brutal, merciless and systematic injustice for one real purpose, to make capital gain.

Anthony S. Wohl, Professor of History at Vassar College writes that during the nineteenth century theories of race were advanced both by the scientific community and in the popular daily and periodical press. In his article The Function of Racism in Victorian England Professor Wohl goes on to argue that “to denigrate or point up the bestial, brute, savage nature of an outside group is to point up our own advanced state and protect ourselves against inner fears or tensions. Racism and class prejudice, in other words, not only serve as agents of political power, but also serve as buffers between a community and a nature that seems to be getting too close to it for psychological comfort.”

Social Class ideas in Britain followed many of the arguments that racist classifications did, and were equally pored over by scientists and social theorists. In Britain, class became an issue by the early 19th century. These classes were identifiable groups, and were most notably understood in terms of inequalities in wealth, social power, political power, life expectancy, living conditions, types of job and so on. Race and Class often overlapped, as the Irish would be seen as inferior both racially and in terms of their low-social status. David Cody, Associate Professor of English, Hartwick College argues that early in the nineteenth century the labels “working classes” and “middle classes” were already coming into common usage. The old hereditary aristocracy, reinforced by the new gentry who owed their success to commerce, industry, and the professions, evolved into an “upper class”. Beneath the industrial workers was a submerged “under class” which lived in poverty. It could be argued that in some cases, this structure is still viable even today.

To read the second part of this article CLICK HERE