Nerve writer Lisa Worth has written a feature about the ongoing battle against the Mafia in Sicily

(Photo above of files which are a section of the hundreds of files relating to the case that Rita Atria testified in – the biggest in Italian history)

Corleone, a sleepy Sicilian town at the end of a remote and unsealed road, is synonymous with the Mafia.

Mario Puzo used the name for the family central to his Godfather trilogy, and for a reason. It’s the birthplace of some of the most reviled Mafia families who have controlled the Mediterranean island for over a hundred years.

But a growing movement is determined to redefine the town as a beacon of hope in defiance of the Cosa Nostra, educating school children against the lure of organised crime syndicates.

Santina Lucas, 26, is an educator at CIDMA, a small museum pivotal to this work.

She said: “Education is the key to changing the future. Before, children were told not to speak or even to listen [about the Mafia] but now the focus has changed.”

Through a collection of photographs, documentation and explanation, CIDMA traces the evolution of the Cosa Nostra, and how it has impacted on Italy’s social development.

The museum avoids alliances with politicians, but it is enjoying a growing number of overseas visitors and, more importantly, increasing support from Italians

Santina said: “There is an age divide. Most young people are determined to see an end to its [Mafia] influence, while older people are still reluctant to speak out and avoid answering questions.

They say, why do you want to speak about this?

It’s like some people want to pretend this part of our history was never written.”

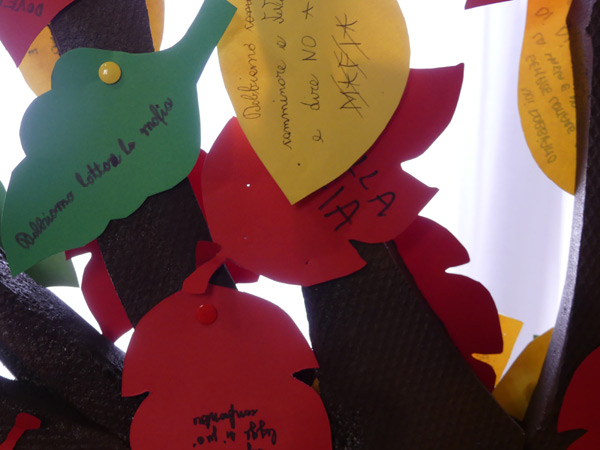

The coloured paper leaves have messages about how to live free of the mafia, written by children and attached to a collage tree in the CIDMA museum.

The photographs at CIDMA are gut-wrenching, illustrating the horror and terror that people have endured. One of the saddest depicts a young boy whose father was murdered for leaving the Mafia.

He is laid out in a cheap coffin on the street, a stone wedged between his teeth. His son has been directed to sit on a high back chair against the head of his father’s coffin, staring in the opposite direction.

The message is clear – this is the only way you leave the Mafia – and the fear and grief in the boy’s eyes tells of the human tragedy.

But the photographic studies also point to how the Mafia secured a grip in the first place.

Abject poverty and institutional inequality provided the perfect petri dish for organised crime, and desperate people had little option but to accept the conditional generosity of the Mafia in return for favours.

Sicily is still the poorest region of Italy, and the country’s stagnant economy is grappling with corruption at the highest levels.

While the trademark slaughter of the Mafia is on the wane, it has cultivated a more legitimate presence in the corporate and political world, replacing dimly lit Palermitan backstreets with boardrooms all over Italy.

So CIDMA’s struggle to maintain the momentum is considerable.

But Santina is very hopeful.

She said: “My family definitely feel the Mafia is less powerful than in the past, but Rita Atria said that the Mafia adapt to circumstance.”

The words on the base of a monument in Palermo read “To the Fallen in the fight against the Mafia”

Rita Atria was born into a Mafia family, but at 17, sickened by the violence and murder that shaped her life, she collaborated with public prosecutor Paolo Borsellino to send 47 mob members to prison in an historic case.

Borsellino became Rita’s only lifeline after her whole family shunned her.

He too paid the price for his work and Rita, terrified of her fate now her only protector was gone, took her life.

For Santina its people like Rita that inspire her to continue the fight.

She said: “It’s hard to say that the Mafia will be gone one day, but we need to believe it. I look at the [collage] tree in the museum with beautiful paper leaves, bearing sentences of hope from the children. I hope to see it, in my lifetime at least.”

With the rise of the extreme right across Europe, it’s hard to be optimistic. Increasing austerity, inequality and reducing opportunity are not conducive to a positive social shift, and where one crime syndicate is diminished another springs up.

But Santina and her colleagues will persist with their courageous fight.

She says: “Evil grows faster than good, but Sicily can teach people – teach the world – do not give up. No, not ever! ”

Permalink