| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots

Tate

Liverpool

Tate

Liverpool

30th June till 18th October 2015

Adult £10 / Concession £7.50

Reviewed by Sandra Gibson

Jackson Pollock was massively important in the development of Abstract Expressionism and technical innovation. His famous "action paintings" - like Warhol's screen prints and Matisse's cut-outs - have long been absorbed into popular recognition. The Blind Spots exhibition addresses Pollock's work at a time of transition from this widely known abstract painting to a more figurative monochrome phase. For both he used his innovative drip technique, perfected in the years 1947 - 1950, which involved him pouring and flicking paint onto a canvas placed on the floor. However, the paintings of the new phase are relatively unknown. This might be because these "black pourings" received a mixed critical reception, one art historian, Michael Fried, saying they were of "virtually limitless potential", whilst another begged him to do them in colour!

The first room of the Blind Spots show greets you familiarly with what most people would regard as a 'typical' Pollock. Summer Time Number 9A, 1948, is a long painting with repeated looping abstract motifs, giving the work a rhythmic kinetic power: an impression enhanced as you walk alongside it. In terms of composition there is not a main focal point, but evenly distributed, predominantly warm- coloured areas on which the eye rests in turn: the reds, yellows and oranges advancing, the blues and greys receding, giving some depth to the picture plane. The monochromatic pourings of linear nerviness, so characteristic of Pollock's Abstract Expressionist style, represent the unconscious forces with which the artist worked, whilst the colours are areas of conscious artistic intervention. It is this balancing that gives the paintings their dynamic equilibrium.

In an era when all artistic conventions have been challenged, it is easy to overlook the radicalism of removing the canvas from its traditional vertical easel position to the horizontal floor position. The Orientals had done this but it was unusual in contemporary Western art. What this facilitated was an aerial viewpoint, rather than the post-Renaissance perspectival vista, and there are four paintings in the Blind Spots exhibition which illustrate this: Two-Sided Painting, 1950-51, Number 4, 1950, Number 3 "Tiger", 1949 and Number 34, 1949. They all combine the clarity of something emerging with the obscurity of complex, unspecified detail. It's a bit like Google Earth.

Even more radical was Jackson Pollock's method of application, which counted on gravity as an agent. In moving his body over the canvas to pour, spray and flick paint, he was using more than just the energy of his hand, arm and shoulder - he was engaging his whole body. He could apply paint in a multi-directional way; he could step inside the painting; there needn't be a right way up; there needn't be one focus. Of course, some control is there; it isn't the anarchy of an infant running amok with paint and freedom, but in relinquishing the hand/brush/precision of tradition, by creating a gap between paint and its eventual surface, he is embracing a greater element of chance in his mark-making, though he didn't want to eliminate precision either - hence his use of the syringe. A particularly good example of the virility and versatility of such a practice is Untitled (Black and White Polyptych), 1950, in which there are impactful areas of thrown black paint, then spatter marks outwards and thinner lines, in which the directional energy of the flicked paint is pervasive, but to a certain extent controlled. The unconscious - as well as conscious - energy of mind and body, untrammelled by restrictive painterly conventions and abetted by gravitational force, thus plays an increased part in the painting. And this is what Pollock had perfected and this is where Pollock found himself when he allowed photographer Hans Namuth to film him working in 1950. This is Namuth's account of the shamanic event:

A dripping wet canvas covered the entire floor …There was complete silence … His movements, slow at first, gradually became faster and more dance-like as he flung black, white and rust colored paint onto the canvas. He completely forgot that Lee and I were there: he did not seem to hear the click of the camera shutter … My photography session lasted as long as he kept painting, perhaps half an hour. In all that time, Pollock did not stop. How could one keep up this level of activity? Finally, he said, "This is it".

And this is what Pollock did next: after two years of sobriety, he started to drink. Thus began his 'black period': in retrospect, a pivotal moment in which he turned away from colour and in which he brought figurative elements into his work. This isn't to say that Pollock was a colourist; his coloured paintings tend to have a lot of black and white and grey in them. And it isn't to say his work was entirely non-figurative: there is a definite presence in the nervy, linear delicacy of the motifs in Untitled (Silver Square), 1950, for example. Just as the conscious and unconscious elements co-exist, so it is with the abstract and the figurative.

|

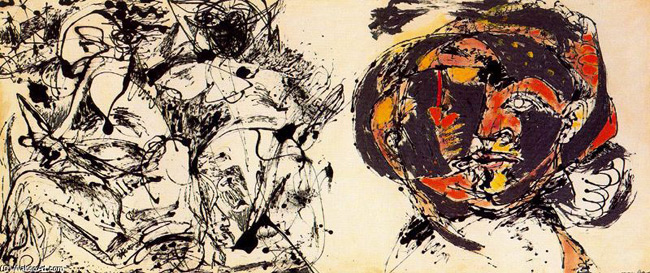

| Portrait and a Dream, 1953 |

However, as we get into the post-1950 works, the sense of encroaching darkness increases and the laboured emergence of the figurative becomes more prevalent. Is it emergence or obliteration? Just how prescient is the monochrome figurative piece: Untitled, 1944, where the artist has used a found collotype print and partially covered the mother and child with ink? There is some over-drawing to highlight but the main impression is not this detail. It is the obscuration. Among the later 'black paintings' there is some colour use, as in Number 2, 1951, but how the black dominates the areas of dried-blood red, dark green and dulled yellow! And although Yellow Islands, 1952, sounds cheery, it has a focal area of black: black dripping downwards. Number 7, 1952, which has a focussed sense of portraiture, has splashes of red and yellow paint as if by accident.

It is this sense of heavy-handedness that one experiences in Untitled, 1951, after Numbers 19, 22 and 9. These are three black and white screen prints on laminated Strathmore paper, which contain limbs and faces and are reminiscent, in their black heaviness, of German Expressionist wood cuts.

In terms of the emergence/obliteration balance, Number 23, 1951, Frogman, leaves little doubt: the 'eyes' are just about there, but threatened by the omnipresent swirling black. Although one can find exceptions, where there is a return to abstraction, such as the craggy Brown and Silver 1, 1951, and the tumultuous Number X 1951, there is an increasing use of the figurative. Although we find more optimistic colours, such as Number 12, 1952, with its sunlit green and its balance of blue and yellow, where the areas of black have been reduced to floaters in the eye, and there is even a bit of reflective silver, we are invariably back to black. There is an awareness of physicality; a sense of the claustrophobic darkness of the realms of hell; and an expression of mental turbulence in the nervy lines and swirled paint. Spiritual drowning is the main event here. Some of these images are reminiscent of Goya and almost Mediaeval in their expression of fear and pain: look at the self-loathing in the defaced portrait, Portrait and a Dream, 1953. In terms of the function of the artist to examine the human condition, by swinging the balance away from the abstract and towards the expressionism, Pollock has done his job well, but unlike the paintings in an age of faith, there is no redemption.

Nothing redemptive then?

Jackson Pollock expressed an interest in specialising in sculpture, turning to it when under pressure. He made about twelve three-dimensional pieces and there are a few examples in the exhibition: maquettes, which would be the models for larger pieces. They do not offer much in terms of optimism: there's a small head: stone and dark and still, like a death mask. What is depressing is the smallness. There is an abstract piece in plaster, sand, gauze and wire, displayed on mirror so you also have the underneath perspective. It is like something hung out to dry; something from a desert. Yet, who knows? Perhaps the process of making the sculptures large scale would have been exhilarating for him and might have helped him with his demons by counterbalancing the edgy hyperactivity of action painting with the slow, precise, meticulousness of sculpting.

The last room of the exhibition allows you to leave on a lighter note. It contains some small, intimate, essentially decorative pieces that have a sense of oriental restraint, balance and minimalism wholly in keeping with the Japanese paper on which they are made. There is some joy in the controlled spontaneity of these ink and water colour works, which indicates the extent to which the textured paper raised Jackson Pollock's spirits, even in the dark days of 1950 and 1951.

Jackson Pollock died in 1956. His death was, in effect, a constructive suicide, though driving whilst drunk does allow an element of lucky chance. But chance decreed his death and we are left wondering if he would ever have worked his way through to a resolution in which the frogman emerged from the slurry rather than drowning in it.

Blind Spots presents an effective experience of bi-polarity.