| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Back to index of Nerve 22 - Summer 2013

Who has their finger on the button?

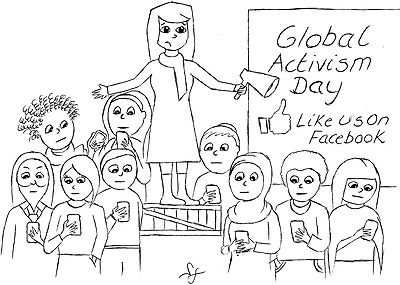

Samantha Fletcher argues that we should learn from the State’s reaction to “Occupy’s” use of social media to organise.

The

number of people involved in the occupation of physical spaces in Liverpool

was a fraction of the 5000+ ‘likes’ of the “Occupy Liverpool”

Facebook site. One of these ‘likes’ is mine, in support of

those that were out in the public domain, reclaiming space and contesting

various manifestations of inequality. At the time of clicking the ominous

‘like’ button in virtual solidarity with the activist network

that had taken to the streets, I had to acknowledge I was sitting on my

sofa being distinctly inactive.

The

number of people involved in the occupation of physical spaces in Liverpool

was a fraction of the 5000+ ‘likes’ of the “Occupy Liverpool”

Facebook site. One of these ‘likes’ is mine, in support of

those that were out in the public domain, reclaiming space and contesting

various manifestations of inequality. At the time of clicking the ominous

‘like’ button in virtual solidarity with the activist network

that had taken to the streets, I had to acknowledge I was sitting on my

sofa being distinctly inactive.

In light of a number of incidences of violent responses by the state to occupiers of physical spaces globally, and ever more insidious legislative reform designed to criminalise protestors, the ‘like’ button can emerge as an attractive alternative rather than a useful accompaniment to the movement*. Problems emerge when these State responses encourage the solidarity shown on the streets to retreat solely into the virtual world. That being said, it shouldn’t be a case of choosing either physical or virtual spaces as the ‘legitimate’ site of protest. Instead we should understand both elements and how they might be used meaningfully.

A few months ago someone from “Occupy” told me they felt that a significant aspect of “Occupy”, and subsequently one of its key strengths, was its capacity, through various activism strategies, to provide an opportunity for people to break free from ‘normal everyday life’; the mundane predominant influence of capitalism. For many people there is little ‘out of the ordinary’ about using social media as a platform for protest, but this form of interaction only seeks to reinforce a distinctly mundane and highly common modus operandi.

Social media platforms are accompanied by a convincing rhetoric of people being ‘better connected’, when in fact sitting in isolation ‘liking’ a Facebook group can be a distinctly solitary process. Social media technologies are ‘double-edged’; on a spectrum from useful to detrimental activity. However, there is arguably a potential danger that social media could become a tool that can smooth the progress of a stealth-like wearing away of the potential of activism.

The

systemic problems of capitalist accumulation and increasing inequality

occupy all our worlds including both the physical and virtual. There is

thus arguably a need to continually seek ways to match this occupation

by reclaiming both physical and virtual spaces and marking them with positive

discussion about possible alternative futures. However, our interaction

with the virtual requires constant and considered reflection on when it

does and doesn’t support this aim. One should not forget that when

virtual online activity is meaningfully deployed to facilitate a physical

process of protest, resistance or protest on the streets, the State and

its facilitators show high levels of anxiety and rumours circulate, particularly

in the UK and US, about potential ‘Blackout’ buttons that

might become available and deployed at the will of the powers-that-be.

There are actual examples of the State shutting down popular social media

platforms when the virtual world is used to facilitate a physical real

world protest, such as that of the events in 2011 in Tahrir Square, Cairo.

The

systemic problems of capitalist accumulation and increasing inequality

occupy all our worlds including both the physical and virtual. There is

thus arguably a need to continually seek ways to match this occupation

by reclaiming both physical and virtual spaces and marking them with positive

discussion about possible alternative futures. However, our interaction

with the virtual requires constant and considered reflection on when it

does and doesn’t support this aim. One should not forget that when

virtual online activity is meaningfully deployed to facilitate a physical

process of protest, resistance or protest on the streets, the State and

its facilitators show high levels of anxiety and rumours circulate, particularly

in the UK and US, about potential ‘Blackout’ buttons that

might become available and deployed at the will of the powers-that-be.

There are actual examples of the State shutting down popular social media

platforms when the virtual world is used to facilitate a physical real

world protest, such as that of the events in 2011 in Tahrir Square, Cairo.

The State’s anxiety over transference of protest from the virtual to the physical world is not shown when protest remains solely in the virtual realm. One can hardly envisage someone running down a corridor into the PM’s office to declare “Sir! Sir! They’re all liking a group on Facebook. What should we do?!” It’s not always easy to distinguish between technology as a medium for facilitating movements such as “Occupy”, and technology as a medium that conversely has the potential to undermine the efforts of such movements. However, the emerging signs of State responses and its visible angst when the virtual facilitates activism in the streets, would suggest that perhaps the State is beginning to make that distinction more readily than the movements themselves. The concerns of the State could potentially provide a useful ‘tell’ in an often stoic poker face, and we might do well to learn from and explore the significance of these responses in greater depth.

*Note: Although it must be recognised there are many justifiable reasons why people do not physically occupy, instead participating in the “Occupy” movement via other means. This could include medical reasons, or some of the most precarious work-life balances seen since the 1980s.