| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Back to index of Nerve 18 - Summer 2011

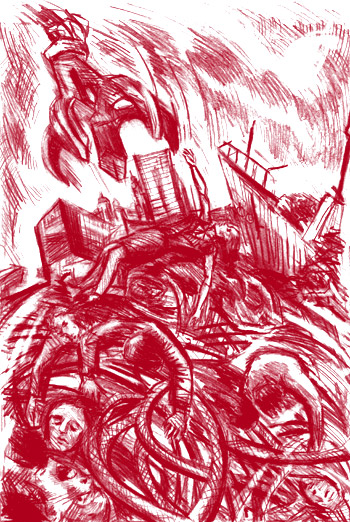

Casualism - back to the future?

"Over time there have been many accounts of

the vision that greets people as they enter the port of Liverpool. Today

a mile long metal mountain lines the banks of the Mersey. Who would have

thought that the second port of 'Empire' would become the scrap capital

of Britain? What is barely glimpsed is the low wage, hazardous hell. This

is part of the post-industrial landscape, where our politicians believe

in a fairy tale notion of regeneration as a way of restoring the lost

prosperity of Liverpool."

Tony

Wailey and Steve Higginson

respond to this statement made by NERVE

Perhaps

we should state straight away that the port was never pretty and that

is why we always needed the Pier Head. And need it still as a turn around

facility for liners to berth and sail from there today. It is equally

well to remember the issues of Casual employment and Time which characterised

the general transport strike a hundred years ago in Liverpool. At its

heart this was a strike for liberty against the tyranny of the clock and

an explosive need of a mass democratic impulse to obtain that objective.

Perhaps

we should state straight away that the port was never pretty and that

is why we always needed the Pier Head. And need it still as a turn around

facility for liners to berth and sail from there today. It is equally

well to remember the issues of Casual employment and Time which characterised

the general transport strike a hundred years ago in Liverpool. At its

heart this was a strike for liberty against the tyranny of the clock and

an explosive need of a mass democratic impulse to obtain that objective.

Casualism provided a collective pursuit of action at the port; it possessed a radical spontaneity and was based upon the irregular nature of the work that arose from a ‘gang’ culture. The culture of casualism however was much richer than individuals exercising individual choice at the workplace.

As we search for connectivity in our current circumstances against the rampant alienation associated with the production processes and individual casualisation of the workforce, we might think of Frederick Winslow Taylor. His theories on the unitisation of time and the capability of controlling each worker’s production have gained a resonance these days, but were first expressed in the early 1900s.These processes were resisted by seamen and dockers during the strike. In our own time, if present trends continue, the only collectivity we could witness will be through the console of a networked computer.

The Liverpool Transport Strike involved dockers, seamen, carters, rail and tramway men for most of that long, hot summer of 1911. It meant that the democratic impulse transformed trade unionism on Merseyside. For the first time, general trade unions were able to establish themselves on a permanent footing and become genuine mass organisations. Issues concerning time and speed up of loading and unloading ships, the speed up of individual time, were resisted. At the waterfront, there was always both a demand for freedom and a concept of sharing.

Organisation was never an easy option then or now. The historian Eric Taplin comments that, ‘indeed the enthusiasm of the rank and file for their unions, their determination and militancy was often greater than those that led them. The individualism endemic to casualism when directed into collective action proved to be a formidable force that branch officials and union executives often found difficult to contain.’

The mass organisation that brought 80,000 onto the streets of Liverpool was based on a reservoir of casual and casualised workers, even amongst the skilled trades. Any attempt to ‘rationalise’ casualism in this collective form was always resisted. Richard Williams’ monograph written in the aftermath of the 1911 victory was entitled ‘The Liverpool Docks Problem’. Its basic premise was how to accommodate 30,000 dockers at the port when at its maximum there were only 20,000 jobs. Williams commented ‘no docker would tolerate the loss of another’s job even if both were to half starve’.

That was anathema to Social Reformers and Urban Regenerationists. Charles Booth, social reformer and brother of William the Liverpool ship owner, said of them ‘Communism is a necessity of their lives, but economically they are worthless and morally worse than worthless’. Liverpool has always suffered from unemployment, but there have always been here competing concepts of time management.

Work discipline was fluid. This was the tradition of a maritime culture. Edward Thompson in one of his seminal essays describes a pre industrial, irregular work pattern as being, ‘one of alternate bouts of intense labour and idleness wherever men were in control of their working lives and provokes the question whether it is not a natural work rhythm.’ He was sceptical on whether the natural work rhythm had ceased in port cities.

Part time work within a framework of sporadic employment always characterised the waterfront when up to 60,000 were employed there between the sea and docks. Similarly for women, who between the wars were Liverpool’s proletariat, Thompson compares their role to concepts of time and work discipline and notes that, ‘the role of women’s work is…not wholly attuned to the measurement of the clock’.

If we fast forward 50 years to the 1980s, at the time when Liverpool’s already shallow post war industrial structure was being dismantled, the social economist Ray Pahl was writing about the increasingly ‘informal’ nature of the economy, with all its consequences in terms of ‘freedoms’, ‘pernicious control’ and individual casualisation associated with developments in technology and proposed unitisation of cyberspace.

This process has continued through the dereliction and regeneration that has characterised the city over the past quarter century. The human fallout associated with Alan Bleasdale’s Boys, and Rob Reiner’s Fair Days Fiddle, suggests however that a wider resonance prevails; that concepts of time and the fluidity of time have been far more prevalent on Merseyside than anywhere else. Major industrial disputes concerning the docks, cars and communication workers, had far more to do with issues of time discipline than wage disputes. It is as though the historical genesis of casualism here, the early dart, three on the hook, three on the book, the welt, the job and knock was inbuilt into the DNA of the area. It remains the biological culture of the Mari-time.

Perhaps it is time for an old idea in the new situation of today. A large part of indigenous labour in the Liverpool region now shares some typical characteristics of the conditions of migrants and vice-versa. The migrant exemplifies the most apparent mode in a situation which faces a large part of employed labour in terms of loss, worry, anxiety and the individual casualisation of the most permanent of jobs. In Liverpool today we are all migrants in the face of a gathering storm of cuts and capital consolidation, where the push of a trader’s button still chases the bourgeoisie across the world, just as the waterfront teemed and swarmed in its opposition in 1911. What kind of union now is capable of grasping the connections between production and reproduction, labour and non-labour, culture and material interests?

Many of the historical tides still wash across Liverpool’s shore. Organising them loosely is perhaps the key to development. One hundred years after 1911 it was an ex Liverpool Docker that became General Secretary of Unite, the Transport and General and Engineering workers union; a third Merseysider to hold that post from the docks and the seagoing communities of the region.

Will the two principal points of application of union activity, the “fixed term workers”, that is those that pass several times, in one sense or another, the frontier between labour and non-labour, and the migrant/long term unemployed, the old, the poor, the sick, from outside the city or work community, will they be able to organise together? Perhaps that is an old idea but it also contains within it, the seeds of a new imagination.

Rhythms that carry today? Merseyside has the highest density of organised labour in the UK: a fitting testimony to the democratic tenor and feelings of 1911. But we live in a world where the manufacturing base of the UK is barely 8%. There is a huge disparity in wealth; more and more employment is service/servile based within an accompanying low wage economy. Wage growth has stagnated over the decades, and this has led low-income workers to take on more and more private debt to fill the gap that an organised living wage used to fill. The TUC has recently published figures showing that levels of unpaid overtime/work have a monetary value of £38 billion per year. And like 1911, we are asked to believe that out of private greed comes public good.

We inhabit the age of the instantaneous, whereby our time is solely the here and now. But even though we might live in this world, we still have a greater need of our history. In terms of ships and seafarers, even if we see an end to the maritime tradition by the 2050s we still have to re-imagine it; to see the ideas that came from the river as an organising principle. That from 1911, the collective clamour that sprang casualism from below be seen as a force that has left a lasting consequence. We suggest that for our times the same impulse from below needs to be harnessed, work and non work, absence and presence.

For a generation who assume that because they have grown up with the Net, that the Net is grown up - there remains a void. How can we move from the individual to the collective? We are in the grip of a system that has all but abolished the world of work as we know it, whilst restoring the worst forms of exploitation. It is as though the clock has been wound backwards with employers having complete control over time, and total power over the lives of workers in the form of a zero hours contract. They share a world resonant with the great reserve army of labour that characterised the period before 1911.

We have left the waterfront now, only to be enclosed within the virtualised unrealities of technology and its intangible economy. How do we re-imagine this oppositional spirit in an individual networked age: that sense of creativity and ownership when so much of working life is so completely individualised, chained to an anonymous equation, a unit, a term in a contract?

How do we re-imagine what it is to be human in terms of community, collectivism, sociability and new forms of democracy when human capital has seemingly become fettered within this digitalised world? The similarities between 1911 and 2011 are stark. It is as though in cyber time and movement we are returning to the future. In Liverpool today, the world of the waterfront and the sea has long gone, to be replaced by a far more desperate form of casual labour, with little of the collective strength that fed the city from the river. Is it even possible to talk of a spirit of resistance?

We need to remember our collective memory of 1911 and the issues thrown up across the waterfront about time, overtime, waiting time, employers’ time and in short, casual time. Just as 1911 produced a new form of labour movement, we need to capture new forms of time, place and space because ours is a city against the water and against the world. It constantly looks out towards a new sense of being. As a global-global waterfront, Liverpool’s edge and marginality was historically linked to a Maritime world. Our job is to recapture that spirit and to go beyond the scrap heaps.

Steve Higginson, Ian Morris and Tony Wailey will host a series of text and image events across the city that present a cosmopolitan view of Liverpool in 1911. They will be at the BLUECOAT in September - October.

Reading:

Ray Pahl, (2001) Market Success and Social Cohesion, Journal

of Urban and Regional Research 25.4

Eric Taplin, (1994) 1911 Liverpool General Transport Strike, Bluecoat

Press.

E.P. Thompson, (1967) Time, Discipline and Industrial Capital, Past

and Present 38

Richard Williams, (1912) The Liverpool Docks Problem, Liverpool

Economic and Statistical Society