| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

Niki

de Saint Phalle

Niki

de Saint Phalle

Liverpool

Tate Gallery

1st February – 5th May 2008

£5 (£4 concessions)

Reviewed by Sandra Gibson

Niki de Saint Phalle worked with Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns; she was the only woman to be invited to join the group Nouveau Realisme; she married Jean Tinguely and collaborated with him on a number of important and famous works until his death, yet there has never been a retrospective of her work in the US. That’s why the present exhibition at Liverpool’s Tate Gallery - the largest ever collection of her work – is important and praiseworthy. Be prepared for shock as well as delight.

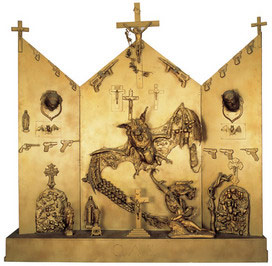

If you think – like I did – that Saint Phalle only produced over-sized seaside postcard females in exuberantly decorated bathing costumes then think again. This exhibition will surprise with its variety, its concepts, its juxtapositions and its contrasts. There are suns with no light; everyday objects rendered sinister through context; shooting targets where heads should be; paintings riddled with holes; an altar starring a bat; ghostly, ghastly brides; political and sexual provocation and – yes – the fat ladies too.

Niki de Saint Phalle had a nervous breakdown in 1953 and started to paint in order to express her fear and rage. Many of her paintings reveal the landscape of an angry mind, and critics have speculated on its causes, often claiming the Freudian cliché of the domestic patriarch. But she has more targets than one and this raises the status of her work beyond the autobiographical. Tu es moi (1960) is an uncomfortable assemblage of tools and weapons laid out like surgical instruments on plaster of Paris, all under a matt black sky dominated by a serrated disc: a sun of blood red viscous pigment. The title acknowledges ownership of the impulse to harm. The title of the painting also sounds like ‘Tuez-moi’ - an invitation to be the assassin? And ‘Tu et moi’ – recognition that our common root condition is anger? The chilling detail is that the agents of death are angled in such a way as to invite the spectator to pick them up and one is momentarily tempted…

We have the weapons – what of the victims? Arguably the artist herself, since she did attempt suicide. But both Hors d’oeuvre or Portrait of my lover (1960) and Saint Sebastien (Portrait of my lover) (1961) shift the emphasis. The lovers’ heads have been replaced with a target; the point made even clearer in the unfortunate Sebastien’s case for his shirt is full of nails – an ironic allusion to the martyred saint – that magnet of homoerotic interest.

In the series Shooting Picture Galerie (1961), the aggression is directed at the artwork itself and evokes the Dada gesture of shooting at random into a crowd. Saint Phalle constructed the paintings to contain pockets of pigment released when they were pierced by bullets to run like multi-coloured blood, in an action painting worthy of Jackson Pollock. Contemporary footage on show at the gallery shows fellow artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns shooting at paintings Saint Phalle had produced in their style. One can speculate upon these acts of apparent destructiveness: the art establishment was overwhelmingly male, for example, but perhaps Saint Phalle was also celebrating the concept upheld by the Surrealists and Dadaists of a previous age: of the chance of beauty to be found in the random act and something she said bears this out: ‘In 1961 I shot at my art because it was fun and it made me feel great. I shot because I was fascinated watching the painting bleed and die. I shot for that moment of magic. Ecstasy. It was a moment of scorpionic truth.’ But it goes further perhaps – into the moment of existential awareness such as one finds in the work of Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Sometimes the message is clearer; some of the shooting pictures are overtly political. King Kong (1963) is an apocalyptic and eerily premonitory painting, which contains the heads of various politicians including, curiously, Donald Duck and Santa Claus in a fairground game of shoot the leader against a background of aircraft and vulnerable skyscrapers. This piece came out of the tension of the Cuban missile crisis as did the grotesque and conjoined Kennedy-Khrushchev (1962) figure, referencing the hotline that now linked them. Encrusted with weapons, gross and cancerous, the two leaders are indistinguishable and horrific…and lewd.

Saint Phalle called the sculptures for which she is most popularly known ‘Nanas’ from the argot word meaning a ‘broad’ or a ‘chick’. Her inspiration for this series was the pregnancy of her friend and in these wire netting and papier-mache sculptures the female characteristics are exaggerated; the heads made small. It’s easy to interpret these as part of the artist’s feminist horror at the subjugation of the self to sexual objectification, and one sculpture in particular: Pink Birth (1964) is arguably one of the most grotesque manifestations. The hair red; the body corset pink; encrusted with plastic animals and weapons of war, a doll hanging out of the vagina – this is a being that looks as if it has been turned inside out, its soft parts made vulnerable to all and sundry. Yet there are other Nanas that are voluptuous and fertile, exuberant and confident, huge goddesses beautifully and playfully adorned. It’s hard to know what to make of this and perhaps Saint Phalle was ambivalent herself.

The designs for the Tarot Garden – finally realised in Tuscany, inspired by Gaudi in Spain, Simon Rodia in the US and Joseph Ferdinand Cheval in France and dedicated to the love of her life, Jean Tinguely – have a celebratory quality, an emphasis on decorative power: playful, resourceful and highly colourful. If one looks back at Saint Phalle’s earlier work: Family Portrait [1954-55] and Pink Nude with Dragon [1956-58] for example, the urge to decorate is all there, though colour-muted and rather frantic when compared to this later work.

Having encountered the low-energy disappointment of the recent Turner Prize exhibition also at the Tate, I found the Saint Phalle exhibition an exciting experience. I liked the sheer amount of paint and colour to be honest. And it still has life in it, after nearly fifty years.

Congratulations to Tate Liverpool for this courageous event in a year celebrating culture.