| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

This is the third in a three part series by Chumki Banerjee on her love for vinyl. Read Part 1 - Vinyl Addiction, My Plastic Predilection and Pushers Tales and Part 2 with interviews with Bob Packham from Cult Vinyl and Carl from Hairy Records.

Vinyl Addiction, My Plastic Predilection and Pushers Tales (those that deal in the hard stuff) - Part 3

By Chumki Banerjee - 7/4/2014

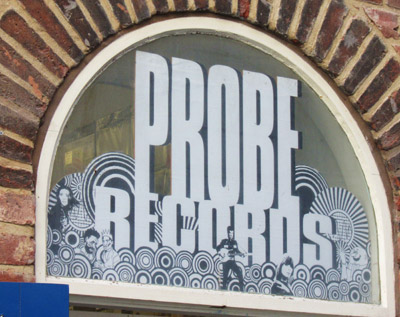

Interview with Geoff Davies of Probe and Probe Plus

An omniscient

child of a certain time, place and musical climate, Geoff literally pulled

the rug from under his own feet, quitting the carpet showroom, taking

a trip in more ways than one to float his own magical mystery carpet,

Liverpool’s first independent record shop, Probe,

shrouded in mists of box like 34 Clarence Street, before ascending the

steeply sacred steps of Button Street, at cusp of Mathew Street, where

it stood as a burning icon of an era, a beacon to those brave or cool

enough to mount its teetering tower, enjoined ten years later by its satellite,

Probe Plus record label. So far the sometimes

bumpy but always scintillating, mind expanding journey, probing outer

reaches of prescient chaos has lasted over forty years and shows no sign

of abating exploration of an endlessly fascinating musical universe and

twisted crenulations of that infinitely more complex inner space, Geoff’s

mind.

An omniscient

child of a certain time, place and musical climate, Geoff literally pulled

the rug from under his own feet, quitting the carpet showroom, taking

a trip in more ways than one to float his own magical mystery carpet,

Liverpool’s first independent record shop, Probe,

shrouded in mists of box like 34 Clarence Street, before ascending the

steeply sacred steps of Button Street, at cusp of Mathew Street, where

it stood as a burning icon of an era, a beacon to those brave or cool

enough to mount its teetering tower, enjoined ten years later by its satellite,

Probe Plus record label. So far the sometimes

bumpy but always scintillating, mind expanding journey, probing outer

reaches of prescient chaos has lasted over forty years and shows no sign

of abating exploration of an endlessly fascinating musical universe and

twisted crenulations of that infinitely more complex inner space, Geoff’s

mind.

Until recently, scientists remained convinced that outstripping light was an impossibility but Star Ship trouper Davies has always tested logic, shining his beam so far ahead that his brightly trailing tail of revelations sometimes struggles to reach us scientifically correct mortals lagging infinitesimally behind.

I always trust Geoff’s judgement and, through his persistent, prophetic passions, have encountered some of the most moving music of my times; including one of my favourite bands of all time Gone To Earth; so I always listen out for his Probe Plus outpourings, safe in the knowledge these are no tentative prods but full on immersion. Wisely or not, he has been my inspiration from the moment I met him many eons ago, for how to live life with utter conviction, belief and a rumbling grumble. Sadly even such a hero cannot make a wise woman out of a fool who persistently rushes in, but my admiration remains untainted and I continue stumbling endeavours to learn from his lips.

So, I make no apology for the length of my interview with Geoff, but instead send him eternal thanks for his infinite patience. I hope you enjoy the words of these three wise men – who come bearing most precious of gifts – as much as I did.

This whole interview was punctuated with my oooh, aahhs, wows and gales of laughter; ‘Garrison Keillor’ of Liverpool life; I only wish you could have been there to hear Geoff’s story with your own ears.

CHUMKI: You

seem to have a passionate relationship with vinyl, why do you find it

so alluring?

GEOFF: I wouldn’t like to use the word ‘alluring’. I

was brought up on vinyl, that was all I knew until the move to CDs. Even

then, on reflection, I came to the conclusion that the myth of CDs was

a con, the sound quality wasn’t as good and their supposed indestructibility,

a lie

So, after a period only buying CDs, rarely listening to my vinyl, I started

to play it again, probably five, six years ago, and I do still continue.

I have so many vinyl records I rarely buy new ones. In fact, I don’t

think I have bought any new vinyl, since they stopped making vinyl.

The sound quality of vinyl is definitely better, particularly for rhythm

based music, whether jazz, rock, whatever, particularly the bass, there’s

a certain sort of feel to it.

Leaving aside questions of quality, CDs have an advantage when it comes

to classical music, at least you can get a whole Mahler symphony, for

example, which might be two hours long, onto one CD, whereas a good vinyl

recording, with space between the grooves to avoid overcutting, only stores

something like 40 minutes, over two sides.

CHUMKI: Though

‘sane’ Liverpudlians are an anomaly, those musical ones that

are compos mentis, in their own sweet way, invariably regard Probe with

awed reverence, tempered with shiver of fear. What insanity drove you

to dive into the independent record industry in the ‘70s?

GEOFF: From answering this question, in various forms, many times before,

this could take a while

I was in what they call a ‘good job’, working for a carpet

manufacturers, a Kidderminster firm, and ended up looking after their

business in the North West. Mercifully, I didn’t have to deal with

the general public or transactions as such. I would provide advice for

valued customers of the likes of George Henry Lees, now John Lewis, who

wanted quality carpets, and contract clients, like pubs and restaurants.

CHUMKI: Why

carpets?

GEOFF:

It was just a job I could get. I had been travelling, as far as India,

North Africa, Nepal, all around the Middle East, Afghanistan, Iran, I

was away for about eight months and couldn’t get a job when I got

back, just before Christmas of 1964.

GEOFF:

It was just a job I could get. I had been travelling, as far as India,

North Africa, Nepal, all around the Middle East, Afghanistan, Iran, I

was away for about eight months and couldn’t get a job when I got

back, just before Christmas of 1964.

I was really not the normal person they take on, but I applied. The fellow

who interviewed me was then the manager of the showroom/office, above

Marks and Spencer on Church Street, two floors up, with an entrance on

Basnett Street. It was dead plush, all suede and velvet curtains, I started

there as a not so junior, junior and then became the North West manager.

It was a cushy job, half nine to five, quite good in a way, but they want

you to go further up the ladder and at this time, late sixties, early

seventies, I was enjoying myself so much in Liverpool, I didn’t

want to be sent down to the South East, or wherever and become an area

manager, I didn’t want to do the normal progression thing. In addition,

I had been taking acid since 1969 and it makes you see things in a different

way. You look down on yourself, your life and what you are doing and I

saw myself leading a double life.

Of a day I was sort of behaving myself, which has always been a bit of

a problem for me, having to curb my tongue – I always swore a lot

– be relatively smart with a tie and suit, having gone through a

hippy faze. I had to do something, get out of the ordinary business world,

so I made a decision.

I was talking to a mate of mine, an architect student and said I would

love to have a second hand record shop, because the ones I had gone to

in Liverpool were somewhat unfriendly. For example, the famous one in

Kensington, Edwards, had a bit of a reputation, it had a lot of stuff

but the guy who owned it was a bit miserable and wouldn’t even play

records for you. At one time, I had a little bit of money and thought

I’ll go up to Edwards to buy a couple of records. I had seen two

in the window I think one was Quintessence

and the other a Doors record, I said , “see that one you’ve

got in the window there” – I think it was one of the not-so-good

Doors records at the time – “Do you think you could play a

bit of that, I’ve got the other two”, to which he responded

rather brusquely, “No you can’t play it unless you buy it”.

Or I might say, “See that one there at the corner of the window,

I’m interested in that one ” and it was the same thing, or

he wouldn’t get it out of the window, because it was too far away,

unless I was going to buy it. So, I was thwarted and thought, this is

ridiculous. This was when you could get second hand records for 25 bob,

£1.25 or something like that and I could have bought 2 or 3 records

here but he put me off.

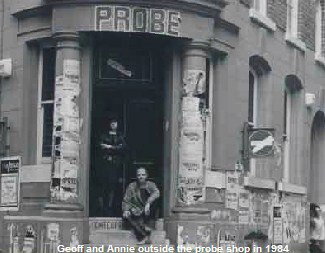

So, I was in the pub, with some student friends of and Annie (Geoff’s

ex wife), that one off Catherine Street, (Kavanaghs?) and was telling

them this, when they said, why don’t you start a record shop yourself?

I’d never considered anything like this, it seemed a big thing,

I didn’t know who to go about it. That was the first seed of it

really, and my first thought was a second hand record shop, so I started

to pursue it.

CHUMKI: How

did you go about it, from there? How did you source your first fix of

vinyl and how did you choose what to initially stock?

GEOFF: That was the problem, the stock. I didn’t know where to buy

it. I thought I could put a lot of my record collection in, most of which

I could get back later.

CHUMKI: So

you were quite a collector?

GEOFF: Yes, I had lots of records then. Also, I knew the ‘Paddy’s’

markets where they had lots of records for next to nothing. They would

just have a batch of stuff, without distinguishing good records from bad.

CHUMKI: How

did you know what would sell?

GEOFF: I wanted it to be music that I liked, specialised really, I suppose.

CHUMKI: What

type of music was that?

GEOFF: Rock, I suppose. By then I was listening to Captain Beefheart,

Love, The Doors and so on, all of that period. Earlier on, it was The

Rolling Stones, Beatles, and the usual really. But I also had jazz records.

I was into jazz from fairly early on, from when I first went to the Cavern

in 1960, when they mostly had jazz bands. I was into folk, blues and stuff.

Also film scores, proper symphonic film scores, which I had been subconsciously

into since childhood, because my parents would go to the pictures. Everybody

in the street I lived, a pretty humble working class street, would go

to the pictures. I was seeing the films my parents were seeing, adult

films, some of the greatest English language directors. William Wyler,

Billy Wilder, Hitchcock, Elia Kazan etc. Practically all of them had the

most amazing music, which has only recently been appreciated. Like last

year was a mad year for film music, there was the Proms, a series on the

TV, Radio 3 had a couple of weeks about it. So, unconsciously, I was getting

used to classical music. Some of these film score composers were actually

classical composers, who had fled Germany or Austria, like Erich Wolfgang

Korngold, who had already written symphonies, concertos and operas and

had to flee Austria, because he was Jewish. He worked at Warner Brothers

for 12 years. I didn’t really know their names at the time but I

was just assimilating their music.

I remember particularly the year I saw The Ten Commandments

with Charlton Heston and so on. I remember walking back from the pictures,

with my mum and dad, trying to keep the tune in my head, the main theme.

I never thought I could buy a record of this. The records we had in our

house then would be literally old ‘78’s, ancient sorts of

things.

Then in the same year, one of the first films I saw without my parents,

one of the first X films I saw, was The Man With

The Golden Arm, which was about a heroin addict, in Chicago, played

by Frank Sinatra, one of his first proper dramatic roles, supposed to

be quite a film in its time, but doesn’t look so good now; I didn’t

know this at the time but Elmer Bernstein composed the score for both

films. It was so different, The Man With The Golden

Arm, everyone knows the main theme, whether they realise it or

not, it’s symphonic jazz, it’s City Music, it can only be

a large American city, you know the first phrase “de dilide din

che che che che che che”. Years later I bought the score of The

Man With The Golden Arm, ironically at Edwards.

Anyway, getting back to the question of how I selected the music to stock

in the shop. Going to The Cavern was, of course, very important because

it was introducing me to jazz, both traditional and they used to have

one night – on Thursday – of modern jazz, mostly British bands

or occasionally an American band or soloist. Then they started to bring

in pop and I saw The Beatles so things started to change. By this time,

at this age, I would be...1960 and I was born in 1943...seventeen, it

was a whole new world opened to me, this was when it was almost a Beatnik

sort of place, scruffy people there with tight corduroy trousers and long

black jumpers. That new world was very important in influencing me. I

could go on and on.

CHUMKI: So

you knew what you wanted and part of it came from your own record collection.

Where did the rest come from?

GEOFF:

I realised I was going to struggle to get enough stock to open the shop,

so then I thought, I’d seen a weird sort of record stall in Kensington

Market; nearly all rock or alternative and some we later called Prog Rock,

which covers a whole area of music. He was selling second hand, and some

new records, which were a few shillings, or 20p, less than the retail

price. That stayed in my head, so I thought, well ok, let’s sell

new records and cut the price of them. So I did that. It was difficult

because, in those days the record companies would require you to have

proper premises on ground floor level, with a window, before you could

have an account with them.

GEOFF:

I realised I was going to struggle to get enough stock to open the shop,

so then I thought, I’d seen a weird sort of record stall in Kensington

Market; nearly all rock or alternative and some we later called Prog Rock,

which covers a whole area of music. He was selling second hand, and some

new records, which were a few shillings, or 20p, less than the retail

price. That stayed in my head, so I thought, well ok, let’s sell

new records and cut the price of them. So I did that. It was difficult

because, in those days the record companies would require you to have

proper premises on ground floor level, with a window, before you could

have an account with them.

At the same time, I was looking at premises on Clarence Street, off Mount

Pleasant. What I had was my parent’s savings of about £300

and borrowings from mates. The first company I approached was EMI who

wanted a £3000 opening order, an awful lot of money, which stopped

me in my tracks. Then I contacted what was then Phonogram, which was Polydor,

Phillips, Track – who had Jimmy Hendrix and The Who – and

loads of different labels under their umbrella. Their opening order was

£1000 and they had this Prog Rock label, Vertigo, which I approached

first. They sent a rep whom I met at my workplace, which looked quite

posh and I had a staff of three. They also required references, including

credit references, but I knew lots of carpet retailers by now, whom I

had done favours for, I had been at the carpet manufacturers for 3 years

by then. So, I just said, can you give me a reference, which was fine

and I wrote the cheque out for £1000, for the record rep, after

which I went round everyone I know and said can you lend me £50,

these were my mates like.

Then when I got this stock in, I went down to Ye Cracke pub, which was

by where I lived, one of my regular pubs, with loads of the stuff I thought

they would be interested in, and that worked, so I was getting cash in,

while selling the records cheaper than people could get them elsewhere,

things like Jimi Hendrix and The Who, trendy things at the time and more

obscure stuff. So that enabled me to progress. That idea started in mid

September of 1970 and I continued building up the stock. The shop was

supposed to open before Christmas, but the building was in such a state,

it hadn’t been used for ages, there wasn’t even a proper floor,

right up to the day before opening they were filling it up with cement,

which – when we opened – was not entirely dry, so we had to

put cardboard over the top.

The shop was absolutely tiny, it’s a Sandwich Bar now, there was

an alley there, owned by the same landlord, and by the end of that year,

1971, because the shop was so tiny, he knocked away the alley, which gave

me another 4 to 5 feet! There was a toilet and sink and the whole place

was very cramped, especially as it got more and more popular.

CHUMKI: So

it was clear others shared your enthusiasms. Was Probe a success from

the start or was persistent persuasion the path to cult status?

GEOFF: Yes we were popular from the start, there were people waiting for

the shop to open.

CHUMKI: How

did you pass the word around?

GEOFF: I just got flyers printed up and sent all round the area I was

living in. I took them round to pubs and stuff. In those days there were

not so many people living further out of town. Lots of people had flats

round Catherine Street and there were lots of students, so I went up to

the University and all that. Lots of the trade was students; there was

the college next door, the university just up the road and the shop was

on the way to walking down to town. So, I would say, at first, two thirds

of the business was students.

CHUMKI: From

humble beginnings to hubris-less hero, what did it feel like on the first

day of the rest of your life, in that tiny Clarence Street shop. What

did it feel like waiting in anticipation for others to enjoy?

GEOFF: Well the first customer

was Norman Killon (Known by some as DJ ‘The Cat’ Killon, Norman

was resident DJ at Erics) whom I vaguely knew from seeing him in the Cracke

Pub, we’d exchange a few words. I think the first record we played

was Layla by Derek and the Dominos which had

only just come out, so was nowhere near as popular as it is now. This

was like ‘Prog Rock’ in a way, or alternative rock. Eric Clapton

was cool at that time because of Cream. We took £57, which was a

lot more than I expected, so I was quite happy with that. We could hardly

move in there because it was so small. That was a Saturday, so I thought

the following Monday wouldn’t be that good, but we took something

similar and it continued.

CHUMKI: How

long were you at Clarence Street?

Clarence Street opened on 16th of January 1971 and about 18 months later

we opened a place in town, in the basement of a hippy emporium –

unfortunately called Silly Billies –

on Whitechapel, going towards the tunnel end, if you’re walking

from Lord Street, on the left, the building’s still there. That

turned out, without planning it, to be more about black music, than rock

pop, more Soul and Reggae.

CHUMKI: Why

was that?

GEOFF: I don’t know why exactly but, early on, we were getting these

Jamaican imports, in the same week they were pressed in Jamaica. A fellow

used to come up from Birmingham, in a van full of albums and singles,

but mostly singles. There was nobody else doing this anywhere near, though

later a place in Manchester started to.

So, in addition to the rock, pop stuff, we were attracting customers for

Reggae and Soul. The last great period for Soul was early to mid Seventies,

people like Bobby Womack, Don Covay, Kool and The Gang, when they were

still cool, Earth Wind and Fire, these were all minority tastes then,

most of these became much bigger later, and there was more obscure names,

such as Bobby Bland, who had done Blues and Soul. I think the shop succeeded

because customers saw this sort of stuff in the shop and got a reasonable

response from the staff, who were willing and able to get records in specifically,

plus the Jamaican imports, which the young Rasta lads from Liverpool loved,

it was like a dream come true for them, to be able to get the releases

in the same week they came out in Jamaica.

CHUMKI: What

attracted you to that music?

GEOFF: I already liked Reggae,

in its earliest forms. With the shop, looking through catalogues, I would

try stuff and Reggae was starting to come up, the important point with

Reggae was the film The Harder They Come which

I think I had just seen. So music by artistes that featured in it had

to be in the shop, I remember getting Jimmy Cliff albums in, for instance.

Then friends of mine were into Reggae, Steve Hardstaff, Roger Eagle, Ken

Murray (Africa Oye) were all around at that time and would wait for this

van to come round on Fridays. They would all be there waiting. Roger Eagle

was more knowledgeable about it than me and he would say, “Yes,

let’s have that Geoffrey”. So, that shop had all sorts of

stuff in, Country – I was starting to like Country and Western –

Blues, Folk, Ancient Folk and so on.

CHUMKI: So

you stocked music that intrigued you?

GEOFF: Yes. Some wasn’t

really my taste but it fitted in, the same people who bought a Frank Zappa

record or Captain Beefheart, could also buy Deep Purple, say. I was never

crazy over Deep Purple but it sort of fitted the shop and people were

asking for it. So, I couldn’t say I loved everything in the shop,

there were some ‘drippy’ singer/songwriters, like James Taylor,

I wasn’t crazy over – a soul act mind – and Carole King,

that album Tapestry probably has never stopped

selling, even now. Everyone had a phase with that, it seemed cool at the

time. If you put it on now, it probably still sounds OK.

CHUMKI: What

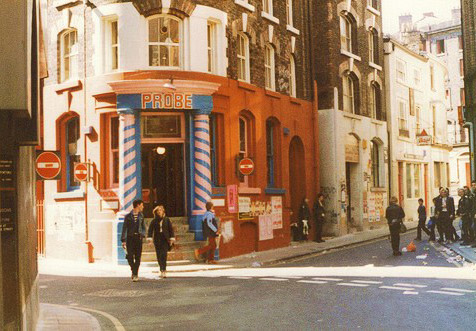

prompted the move to your iconic Button Street premises?

GEOFF:

By 1976, while still at Clarence Street, Roger Eagle had been in touch

with me to say “It’s about time you got down into town Geoffrey”;

he always called me ‘Geoffrey’; “It’s a long way

to walk, up here”. He was thinking of doing some stuff round Mathew

Street and he and this fellow Gary Gannicliffe; one or the other, had

seen this place with a vacant sign above a Button Street shop. So, we

went down to see it, with the view to me taking it on. Roger was interested

in having a bit of it; because it was quite large. Gary, whose first wife

then, was into something called ‘beauty without cruelty’;

make-up without killing animals; also wanted a little bit. The premises

were unbelievably cheap, so I said yes. Fifty yards down the road properties

were three, four, five hundred pounds; this I think was something absolutely

stupid like fifty. It had been all sorts of things, a tea warehouse, a

travel agent. It was partitioned off into small office units, so we had

to knock all those down. I remember going round one Sunday with a couple

of architecture students, friends from the building where we lived, on

the corner of Huskisson Street and Hope Street. With their help, we went

down and smashed the partitions down, which took ages and built this half

circle counter.

GEOFF:

By 1976, while still at Clarence Street, Roger Eagle had been in touch

with me to say “It’s about time you got down into town Geoffrey”;

he always called me ‘Geoffrey’; “It’s a long way

to walk, up here”. He was thinking of doing some stuff round Mathew

Street and he and this fellow Gary Gannicliffe; one or the other, had

seen this place with a vacant sign above a Button Street shop. So, we

went down to see it, with the view to me taking it on. Roger was interested

in having a bit of it; because it was quite large. Gary, whose first wife

then, was into something called ‘beauty without cruelty’;

make-up without killing animals; also wanted a little bit. The premises

were unbelievably cheap, so I said yes. Fifty yards down the road properties

were three, four, five hundred pounds; this I think was something absolutely

stupid like fifty. It had been all sorts of things, a tea warehouse, a

travel agent. It was partitioned off into small office units, so we had

to knock all those down. I remember going round one Sunday with a couple

of architecture students, friends from the building where we lived, on

the corner of Huskisson Street and Hope Street. With their help, we went

down and smashed the partitions down, which took ages and built this half

circle counter.

In this period there were the three shops on the go, Clarence Street,

Silly Billies and Button Street, which opened in October.

The following year, about midsummer, the Clarence Street shop was getting

less trade as customers had no need to walk up the hill anymore. So, there

didn’t seem to be any point to it anymore. So, we closed that; we

had a party afterwards at Erics, Deaf

School played and The Darts. We went

down and started the party at 5 o’clock and went through the night.

Not so long after, maybe six months, the owner of the building where Silly

Billies was went bust and he phoned me early one morning, to tell

me the receivers were coming in and they would grab everything in that

building. I went wow, but I knew someone with a van and we went down to

the building at 9 o’clock in the morning, grabbed everything like

mad and stored it in a mate’s house up the road, in a massive empty

room. Literally as we were going out, the bailiffs were coming in the

same entrance, shouting “you can’t be taking that out”.

So that was the end of Silly Billies and I

was down to the one shop, which was fine.

CHUMKI: What

were the best things about having your own record shop and what made ‘your’

Probe different, special?

GEOFF: Regarding ‘my’

Probe, the earliest days, one thing I liked about having my own business,

my own shop, was to have all these records; I used to get stuff whether

it sold or not, because it had to be there, stuff which I had never sold,

five years later. I had ‘world music’ before they coined the

phrase. There was a firm in Paris and all you could get really was North

African music, Indian music, maybe Turkish village music, some West African

music, such as Fela Kuti. You never really

heard anything from South America, or any further than India, but I used

to get that in and that never really sold. Most of it I brought home myself.

The other thing about having your own shop, is having the freedom, if

someone is getting on your nerves, making an arse of themselves in the

shop, you can just say “fuck off mate, I’m not selling you

a record”. That was a plus for me.

You can please yourself, dress how you like, conduct yourself how you

like and all that sort of thing.

The first Probe was officially open at half ten in the morning but you

were lucky if anyone was there at that time. We closed about half five

but if there were people in the shop, we weren’t that rigid, talking

to customers we might be there past six, or go to the pub, The Philharmonic

or pub down the road; customers became mates. It was a bit of a social

scene. I am sure some members of staff used to do a bit of dope there

as well, because we used to have all these books in there, about how to

grow Marijuana and stock big skins, large Rizlas, Joss sticks and all

that sort of paraphernalia.

The variety of stuff made Probe different.

Then there was the crowd which gathered in the shop. Lots of the people

who went to the Clarence Street shop, transferred to the shop in town

when Clarence Street closed, then we had this other crowd, for the prog

rock and Reggae, that was coming up, with punk crossing over, slightly

later. It required a degree of tolerance to have all these people hanging

around the shop, in some cases, all day.

I particularly remember, in Clarence Street, we used to have two rival

tramps who would come in. One would sometimes sit there for hours and

one who was a bit off his head, would spend ages looking through all the

sleeves; referred to me as Mister, I liked him; he would go through nearly

every sleeve, pick them up, scrutinise them, until eventually, after half

an hour or so, he would come over and put a sleeve on the counter and

I would give him five or ten bob, whatever. Then there was another tramp

who was really quite camp, terrified of the other one; he used to glare

at him. That was all part of it.

CHUMKI: With

so many independent records shops falling by the wayside, what contributed

to Probe’s longevity and do you think there is a future for independent

record shops?

GEOFF:

There are independents and ‘independent’; there are independent

records shops which are not part of a chain, technically ‘independent’

and then there is the Probe style shop, for which there was no model,

its uniqueness is something to do with me, my past experience and life;

I was 27 or was it 24 when I opened it, so I had led another life; also,

with a lot of travelling I was used to all sorts of people, and circumstances

out of the ordinary. I was more cosmopolitan than many Liverpudlians,

of the time, especially those from working class backgrounds.

GEOFF:

There are independents and ‘independent’; there are independent

records shops which are not part of a chain, technically ‘independent’

and then there is the Probe style shop, for which there was no model,

its uniqueness is something to do with me, my past experience and life;

I was 27 or was it 24 when I opened it, so I had led another life; also,

with a lot of travelling I was used to all sorts of people, and circumstances

out of the ordinary. I was more cosmopolitan than many Liverpudlians,

of the time, especially those from working class backgrounds.

It has been said, that my style shop was a first, a real, maybe weird

alternative to some people; not just ‘technically’ an independent

shop, it had its own personality. That ‘model’, if you like,

was picked up by the students that used to come into the shop, some of

whom went back to their home towns to set up their own shop, such as Avalanche

in Edinburgh, which was inspired by the Probe shop, there’s one

in Bristol, there’s Skeleton in Birkenhead,

Action Records, Preston, the big one in Manchester,

you’ll know the name (Piccadilly?).

People would seek my advice about starting a record shop. Probe was the

model for Penny Lane Records. It has been

said, the Probe shop inspired the Rough Trade

shop, as well because Probe started four or five years before them. Don’t

want to blow my own trumpet too much here.

Regarding the future of independent record shop, I think their demise

seems to have stopped, A year or so ago, I heard that something like thirteen

new independent record shops had opened. So the closures seemed to have

somewhat ‘bottomed out’, with independent record shops currently

being trendy, due to programmes on the telly and radio.

As I said before, we’ll still have independent record shops selling

vinyl, CDs, whatever, but they’re not going to be in the centre

of town, in malls, or Liverpool Ones. They’ll be round the corner,

up a hill, in a little street somewhere, without high rents.

You might find a trendy shop in an up and coming part of the East End,

in London, but just to survive on vinyl now, I wouldn’t put my money

into it. You might have a cult shop in London, Paris, New York which just

stocks vinyl, which might survive. Also, there are collectors’ shops

but it can’t be denied that the internet has contributed to their

demise. In the past, rare collectors’ items commanded a fairly high

price, but now they might be available as a download or second hand, new

or used, on Amazon.

Of course the odd physical sources still exist, though maybe further afield;

I went to Ireland last year, or Scotland, where the charity shops have

vinyl at the cheapest prices, LPs no more than 50p and all that.

CHUMKI: Turning

to the casualty which turned my mind to independent record shops and vinyl

and inspired this interview; Hairy Records,

which shut in 2009, when its owner Bob died.

Though I wouldn’t place Hairy Records in the same category as Probe;

a very different cornucopia of vinyl; Hairy holds a special place in

my heart, not only for its chaotic confusion of second hand records, but

also because that is where we were randomly reunited, after many years

of being out of touch. What did Hairy Records mean to you and do you mourn

its loss? Were you a pusher or punter?

GEOFF: Hairy

Records, run by Bob, was a place where I would have a quick look

round. Most of the stuff I had either got or didn’t want, because

it didn’t interest me, or seemed to have been there for years; strangely

Bob didn’t seem to be interested in any music at all, though his

staff , whom I knew from before, were. I knew Carl (Bob’s

manager) from since he was a kid, when he used to come to Probe

on Clarence Street and then in town.

None the less, it was good that Hairy was

there, both in its original location and then further up Bold Street,

not least because, later, it became a place I could sell some records

to.

CHUMKI: What

about when Spike Beecham’s Music Consortium re opened the shop,

revived as The Vinyl Emporium?

GEOFF: Spike, I didn’t actually

know, but I had heard about this fella, being a roadie for Echo

&The Bunnymen or somebody, also as a bit of an entrepreneur.

I got on with him, and though he had some dodgy musical tastes, we shared

a love of Ennio Morricone.

He certainly had expansive ambitions. His involvement with Wow,

a celebration of Kate Bush, at The Philharmonic Hall

may have been a financial burden; an expensive affair. I saw some publicity

and think it was going to be toured, that must have cost him a few bob.

He also spent a lot of money doing up upstairs at the shop, to turn it

into a bit of a venue and cafe, but there are so many cafe type places

in the Bold Street area. In hind sight now, it was probably a bit too

ambitious, especially with the high rents that Bold Street can command.

The rent I had on my first shop was £8 per week, but with a prime

property on Bold Street the landlord can charge whatever, and what with

tax and other costs, you need to take a fair bit of money, to keep things

going.

CHUMKI: So

how did Bob survive as Hairys, especially as he only really used part

of the building for trade?

GEOFF: Well Bob was a bit of a

market trader. He used to go in the early hours of Sunday morning to car

boot sales and all that and he would be very careful with his money. Spike

bought loads of vinyl off me and he’d have a go with Half

Man Half Biscuit CDs, whereas Bob was very circumspect about what

he bought.

I would guess the great contributor to Vinyl Emporium closing would be

the rent and overheads.

CHUMKI: Were

you tempted to take Hairys on after Bob passed away?

GEOFF: No, I had enough of retailing, from earlier jobs I’d had

done. I’d worked in a tailors’ shop on London Road, part of

a big chain, I’d worked in a jewellers/ watch retailer, also on

London Road, which was an education in itself really. Also, while I was

working for the carpet manufacturers, I had a Saturday job in a carpet

shop.

There are some stories from those days, for example in the tailors; where

I worked in the early 1960s, for about 6 years, at their branches on London

Road, Preston and even a couple of days or so in Birkenhead, Rock Ferry;

a lot of the staff were completely untrained, with little education. Some

had been soldiers, with the merchant navy, they were all characters; their

skill was getting on with people. The stories they told, I could have

an ‘evening with Geoff Davies’, just talking about these people.

They went from being odd to completely ‘mad’ to deadly boring.

Though, even deadly boring can make an interesting character. A lot of

time we had nothing to do, so I might be talking to a fellow who had been

in Palestine in the Second World War, who hated Jews, which I thought

was terrible. He would explain that four of his mates had been killed

in an explosion in Jerusalem, so what do you say?

There was another fella who worked there, middle class, posher than anyone

there; still lived with his mother though in his late forties, early fifties;

never heard of a girlfriend or anyone, looking back on it now he may have

been gay, though he wasn’t effeminate; who was obsessed with Franz

Liszt. He know everything about him, he know his piano style; few people

knew he was the finest pianist ever, as well as a composer. That was interesting,

because he would talk about Liszt all the time, give you all these facts,

especially as I already liked classical music then; I used to have classical

music in Probe, my favourite symphonies or concertos, but it didn’t

really sell. People were surprised to find it, and occasionally might

buy a Tchaikovsky violin concerto, alongside Captain

Beefheart or something. Sometimes I would play classical in the

shop and people would say ‘what’s this!’ but though

it might seem boring at times, to some people, there’s no disputing

classical has all the best tunes and melodies.

CHUMKI: So

do you listen to a lot of classical?

GEOFF: (Pointing to his vinyl

collection) I have a whole classical section up there, box sets, jazz

but I hate to say, I rarely play them now, though I am going to get round

to it. Recently I’ve been playing some jazz I haven’t listened

to for years, as I was doing some research for a compilation which I want

to put together, of my favourite Duke Ellington, which is a massive task.

One song, for example Take The A Train or

Rockin’ in Rhythm, might have featured

on many different recordings, taken from his prodigious live output, in

Paris, London, Berlin, Manchester and so on. I’ve been trying to

find and play all these different versions, from vinyl, CDs, so I am going

to be playing more of my collection but you need to have some discipline,

not put the telly on, set aside a couple of hours, to just have a listen.

CHUMKI: Do

you think the intrinsic beauty of vinyl records will continue to captivate

people, or is this a media which will be increasingly consigned to history,

except as nostalgic oddity?

GEOFF: I think it will continue to captivate people, though as a more

specialised/novelty medium. There are people buying vinyl now, who never

bought it before. That might wither away.

CHUMKI: Why

do you think people are coming to it new, now?

GEOFF: There’s a realisation, for one, that the sound quality is

different; also it’s trendy. It’s cooler to go to their local

independent shop, than HMV, Asda, whatever; so there’s that element.

It’s never going to come back as it was, as a mass thing. What will

happen soon is, the ‘buggers’ in this industry, will come

up with another medium; everyone now has their whole record collection

on CD, so they won’t sell anymore of those releases and will find

another reason to ‘con’ the public, with whatever bloody thing;

claiming the best sound you ever heard; you’ve got to get these.

Then they’ll delete CDs, so you have no choice. They will probably

come up with something physical, because people like that; looking at

the sleeve, inserts and so on.

CHUMKI: Do

you think there is a different art to putting together a vinyl album,

as opposed to online releases? Is there a particular pleasure to listening

to a vinyl album?

GEOFF: Yes, the track listing was very important. You always had to start

with a track that grabbed. If that was a fast track, and the rest a mixture

of tempos, you might follow with another, slower ‘grabber’.

Then the first track on the flip side needs to be a ‘grabber’.

What was not un common for people, myself included; it was the first side

that was played most; not necessarily because the other side was lesser,

but it was psychological.

The other thing to bring in here, of course, in the old days, when I was

young; you would buy an album, especially when very young, it would cost

you a lot of money; you might have to save up, or it was the main purchase

that week or wage. So, you take it home, on your own, and you’ve

listened all the way through side one. You flip it over onto side two;

you haven’t got the telly on, you’re not on the computer;

you’re doing nothing but listening to it. In my Hippy days, I would

do it lying on the floor, on cushions, with the two speakers evenly spaced

apart. Even socially, a couple of mates might come round, or another couple

and you’d sit and listen to it. You wouldn’t be jabbering

away, because in those days, there was hardly any alcohol about, so you

were listening to the music properly, without bloody talking. Now, people

come round, you got the wine, booze out; it seems odd to young people

now, to just sit there and listen to a record together.

The other thing, of course, (smiling wryly)

with a gatefold sleeve, you would be doing a joint and listening to music

on acid was simply amazing. Sadly, that’s all changed.

CHUMKI: We’re

certainly missing something without the vinyl! How did the growing popularity

of CDs, as opposed to vinyl, effect your business; and what motivated

you to start Probe Plus, your own prodigious record label, which arouses

such adoring admiration?

GEOFF: Well, by the time CDs took

over from vinyl, I didn’t still have the shop. (Geoff

gave the shop to his first wife Annie, when they separated.) I

held the lease on the building but had moved upstairs to concentrate on

the Probe Plus record label, which I started

in early 1981.

In addition, I was involved with a cartel of independent distributors.

I was asked by Rough Trade, who stated this,

to join, so I was wholesaling records round the North West; independent

records, loads of punk records, that sort of thing. I continued that until

the end of 1984, driving up to the top of Lancashire, Holyhead and places,

selling to market stalls in some cases; Lancashire loved punk, much more

than Liverpool, and they couldn’t get these records; Dead

Kennedys, Crass and all that sort of stuff.

But I was losing money like mad, because a lot of people didn’t

want to pay. Market stall holders I suffered with; Wrexham, Holyhead,

Wigan, Burnley; the procedure was to leave a despatch note for what they

had, then send an invoice for payment within 30 days, but some were just

not paying.

I remember going to Holyhead, trying to find some bugger. I actually did

find him, the shop had closed, but I asked at a neighbouring shop on the

main street in Holyhead; “what’s happened to Dave?”;

they said “ Oh he’s gone”; so I said, “do you

know where he lives? I’m a mate of his”; which wasn’t

true but he owed me about six hundred quid. They said he lived on such

and such estate, the only council estate in Holyhead: “it’s

on your way in, the way you drove in”. That’s all I had to

go on. So I went the estate and asked in the only shop: “I’m

looking for a mate of mine. He used to have a record shop in town”

and the guy said; “there he is, there”. I crossed the road

and he was mowing his garden, right. So, I was walking across and he was

looking at me, like this, right,, saying he was broke and all that, hadn’t

got a penny but “got some of your stock here, in the garage. You

may as well take it back”. It was about twenty albums, all on the

floor, the sleeves all damp and wet; I took them anyway and that was the

end of that.

There was others like that, it was all doing my head in, I was not really

good at getting the money back, never took anybody to court, so I had

to do something. Cutting a long story short, I got out of that cartel

thing and the wholesaling, which freed me up to spend more time on the

label, which was fine because, I had done some records since 1981 and

they were OK but though I went to the studio, I didn’t get as involved

with production as much as I did later on. Towards the end of 1984, that

was the important thing for me

I would be mixing within the cartel, with people from other parts of the

country and some of the distributors, Revolver

in Bristol, Fast Forward in Edinburgh had

started doing records; it seemed to be the natural progression. And, in

1973 I had made Liverpool’s only reggae album, Mr

Amir; a Somali fellow; which got played on John Peel a lot, he

loved it. That was the first LP.

The second LP was The Mel-O-Tones and that

was stuff I really liked; hard and grungy; really good stuff. I didn’t

produce that, but I did attend the recordings and found myself getting

more and more interested, wanting to add my personal touch.

The following year, 1985, I found Gone to Earth,

as you know (CHUMKI: One of my top favourite bands).

From then, I was really only doing, in most cases, things which I really

liked, which I could associate with, I took a real interest in. I ended

co producing things with Sam Davis, known as ‘Shark’

from Deaf School, which seemed to go quite

well.

CHUMKI: What

are your feelings about the move away from analogue recording techniques

to digital?

GEOFF:

I have more or less, always made analogue recordings, Occasionally, I

have started off using analogue techniques, for example to record the

basics, such as vocals, guitar, drums and bass, before taking it to a

digital platform; but that’s only this ‘century’ really

and only with reluctance. Sometimes it feels like I am the last man standing.

People say, what are you spending all this money on recording studios

for? Not that I spend, or have spent a lot on recording studios, but compared

to how cheaply it can be done nowadays, digitally.

GEOFF:

I have more or less, always made analogue recordings, Occasionally, I

have started off using analogue techniques, for example to record the

basics, such as vocals, guitar, drums and bass, before taking it to a

digital platform; but that’s only this ‘century’ really

and only with reluctance. Sometimes it feels like I am the last man standing.

People say, what are you spending all this money on recording studios

for? Not that I spend, or have spent a lot on recording studios, but compared

to how cheaply it can be done nowadays, digitally.

There are many reasons why I prefer an analogue studio; for one the sound

quality. I don’t think digital is as good for any music really;

it’s clean and all that sort of thing but it doesn’t have

that almost, throb or visceral sound connected with analogue and vinyl.

For dynamic sound, the best recording medium, which no one has got any

more is 16 track, 2” tape. There used to be loads, but people foolishly

thought you need more tracks, but if you have more tracks on that 2”,

the lesser the quality. I recorded a fair bit on 2” tape.

A great example of analogue techniques and vinyl, as a great medium for

recordings is Gone To Earth’s first

recording on S.O.S.’s (Alan Peter’ small,

hand built ex recording studio, in the back alley, off Stanley Street

in town) one inch 8 Track. The sound on a one inch 8 track tape

is absolutely fantastic. Cut by Kevin Metcalf, it jumps off the turntable.

When you put the track Three Drummers on,

I’ve never heard sound quality like it, despite the fact it was

recorded in a fairly basic studio. I play that to people as an example

and say listen to the quality of that. You could say it was poorly recorded

technically but particularly Live and Buried

sounded amazing. The band only just learnt that arrangement the night

before, in Manchester, so to play it right through like that, with the

segueways in was extraordinary.

(CHUMKI: That

used to send shivers down my spine. Did you use the same technique with

other bands?)

GEOFF: Suguing tracks, that was

my idea, of course; I loved that idea. I managed to get an extra track

on the Peel ‘session’ for Half Man Half

Biscuit, because they allow you four songs. I said these track

are connected, so we segued them together. The band hated it, because

that is so difficult to do. Perhaps it depended on the band but Biscuit

couldn’t do it like Gone To Earth. On

that session, you can, or at least I can hear the segueway that allowed

us to get five tracks in.

At this point we were interrupted by a consignment of JD Meatyard CDs, delivered to his door by a large white van, and took the opportunity to sup a cup of cha; large leaf, specially mixed by Geoff, with fragrant hint of Earl Gray.

CHUMKI: Talking

of Half Man Half Biscuit, how did they materialise in your dimension?

In early summer 1985, Nigel (Blackwell) and Neil (Crossley) walked up

to the Probe Plus office above the Probe shop,

with this cassette; they were called Half Man Half

Biscuit. I looked at the cassette and said ; “I’m not

going to play it now in front of you, but if it’s half as good as

the titles, I’m interested in it”.; titles like Fuckin’

‘Ell It’s Fred Titmus and I Hate

Nerys Hughes. I played it in the car on the way back home, most

of the first side. The first track was God Gave Us

Life, which, early on, includes the lyrics ‘God

gave us life to take sweets from strange men, in big coats, who want to

take us to the woods and stroke nonexistent puppies’. I said

to Annie “God, did I really hear right’ and she said “I

think so, yeah”. It went on like that and by the time we got home,

it was a short ride, the first side had barely finished, so we played

the rest of it when we got back in. Even after the first side of the cassette,

I thought I must do this and hearing the rest of it, thought it was just

wonderful; never heard anything like it. Nigel came in a week or so later

and I said “yeah, it’s just great, we’ll do an album”.

They were surprised, “an album?!” They were thinking a single,

at the best, because they had been turned down by Factory,

a label in Wallasey, SkySaw and Skeleton

Records in Birkenhead. That was it; I said to Nigel, the recording

quality was pretty bad, which was an understatement really and we would

have to do something about it.

CHUMKI: Where

was it recorded?

GEOFF: It was recorded in Vulcan

Rehearsal Rooms, which didn’t have a proper desk. It was rough,

so I said they would have to re- record it, properly but Nigel said no,

“not bothering with that, it’s all finished” or words

to that effect. So I said, we’ll have to at least do a salvage job,

remix or something, because there were things disappearing, like the bass

just appeared or the guitar was really high and then disappeared. So,

we went down to a studio, for I think, an afternoon, to see if there was

anything we could do with it and then sent it to be cut, which improved

it. The recording cost about £90 and the cut was the most expensive

I had ever done until then; a thousand and something pounds; as it was

such a challenge to cut I went into overtime; after 5 or 6 you have to

pay a higher rate. I had taken the train down, to Utopia,

in London, about 11 o’clock, and in those days, the last train back

to Liverpool was ten to one, but I as I was there so long, and finished

so late, I had to get a taxi across London, which hurt and only just made

the train. The reason it was such a challenge, I had these reels, some

of which had the tape hanging out of the box. Some were just reels in

a supermarket plastic bag and as I am taking them out, the engineer, Kevin

Metcalf, is sighing, despairing at the sight of this and when he put one

on he said; “fucking hell Geoff, you’ve brought some shite

down to me but this is the worst I’ve ever heard”, meaning

the quality of the recordings, rather than the music. I knew him well

enough by then, not to respond, as he starts to press buttons, asking

“does that sound any better?”; I said “yeah”,

which got him started on it.

It was a salvage job but having got the test pressing done, we sent it

to John Peel. I wrote a note saying “All I’ll tell you about

this band is, they are Tranmere Rovers supporters”

and he called me the day he got it, to say he’d just played the

first side, and thought it was great. He said “what are they called?”,

“Half Man Half Biscuit”. He said

he had heard nothing like it and was going to play the other side, after

which he called again to ask if they had any new songs. Having done John

Peel sessions with other bands, I knew what was coming; his ‘sessions’

had to be new, unheard material. Without hesitation, I said “yeah”,

even though I didn’t know, and suspected they didn’t have,

any new songs. So, he asked them down for a ‘session’, in

about three weeks.

When I told the band, Nigel said he had a couple of ideas and beginnings

of song, which Sam (Davis) and I rehearsed with the band at Vulcan,

and knocked them into shape, just about ready, in time for the ‘session’.

By then the DHSS record had come out and was

selling remarkably well, but when Peel aired the session, it went mad,

I suppose they would use the word ‘ballistic’ nowadays, or

maybe 15 years ago. We were so surprised at the sales.

By now, we were towards the end of November, when the ‘session’

came out. By the January of the following year, 1986, it was the biggest

selling independent record, and continued like that for a long time. It

was the biggest selling independent record of that year, which meant a

lot more in those days; the independent charts would be shown in the music

papers, alongside the main chart.

CHUMKI: So

how many did you sell to get to number one in the independent charts?

GEOFF: I don’t know, is

the simple answer, in the thousands. It went out on vinyl and cassette

and then CDs. We put an EP out early 1986, Trumpton

Riots, which went to number one in the independent singles charts,

right away. That appeared on the CD release of Back

In the DHSS and it’s never stopped selling. As far as we

can make out, it sold at least 700 to 800 thousand.

CHUMKI: How

important were Half Man Half Biscuit to your future?

GEOFF: It all started with that John Peel Session, The band with me, Sam

Davis and Suggs, who was his friend. That was the session, in a way, which

changed everything. It allowed me to carry on making records, that hardly

sold at all or I lost money on, for all those years; 29 years. So, thank

god for the ‘buggers’!

We played out with King Tubby, an artiste

whom Geoff greatly admires; warm, sunny, bathed in golden glow of halcyon

bass; full of love and hope, despite tragic end; perfectly encapsulating

Geoff Davies’ inspirational enthusiasm for life and music. Tubby,

a sound engineer, developer of dub; often cited as inventor of the ‘remix’,

and prophet of electronic dance, incidentally and coincidently also neatly

tying up my three of my loves, vinyl, electronic dance and twiddling knobs.

Thank you Geoff and all, my hope is renewed, long live vinyl.

Part 1 - Vinyl

Addiction, My Plastic Predilection and Pushers Tales

Part 2 - Interviews

with Bob Packham from Cult Vinyl and Carl from Hairy Records

Sorry Comments Closed

Comment left by Mike Scott on 15th February, 2015 at 20:27

Probe supplied our shop in Wrexham (Phase One Records) throughout the eighties and it was our independent record sales that really got us going. Geoff would drive to the shop with a load of stuff in his car boot and share a coffee, chat, give us some great advice and sure enough we would sell out the next week. I have great memories of Probe and their influence - we would never have had such a great time without them. Best wishes, Mike