| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

A Conversation with Writer Deborah Morgan

By

Sandra Gibson

- 5/12/2012

By

Sandra Gibson

- 5/12/2012

“Home isn’t always the safest place to be. I’ve lived in other people’s houses.”

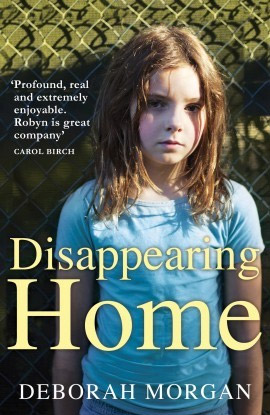

I didn’t know when I arranged to meet Deborah Morgan at the Adelphi that her Nan, on whom she based one of the main characters in her book Disappearing Home*, had been employed there on “silver service” though I did know that Debbie herself had worked as a chambermaid. It was an appropriate venue for another reason: her debut novel addresses the issue of the precariousness of the safe refuge - the “Disappearing Home” of the title - and a hotel is a place of transient occupancy.

Like her main character Robyn, Debbie herself has been homeless and the author recalled the times she had been smuggled into friends’ homes and had squatted under their beds to avoid the adults knowing she was there. “Home isn’t always the safest place to be. I’ve lived in other peoples’ houses, and I was very grateful to those people for opening up their homes to me. It’s not the easiest of things to do.’’

Apart from underlining the fragility of Robyn’s home, I asked Debbie whether the book’s title had other aspects, such as the notion of the home absorbing people into the domestic realm, which, although it offers security, may also stifle the creative energies.

“Yes, I feel that way about the home, that’s why I write away from it. I was making excuses to clean or wash, instead of writing. Self-sabotage. I also meant the title to mean disappearing towards a more stable home, a place Robyn could really call home, without violence and fear.”

Debbie didn’t set out to write about a dysfunctional family; what she had in mind was a children’s book about a witch who lost her magic. However, Robyn came up with her own brand of story-telling magic and this was how the creative flow moved: from an adult wanting to write a kid’s book to a kid’s voice telling an adult story. “Disappearing Home is a combination of things that really happened, some real characters and some composite characters made from various people I knew and some things that are made up. I deliberately kept the language simple.” Debbie has done this in the interests of accessibility and also because her narrator of events is 10/11 years old. The interweaving of nursery rhymes with the narrative and the image of Robyn playing ball against the wall reinforces this. “That was my wall!” Debbie said, recalling the importance of this territorial marking, this sense of belonging to, and owning somewhere. However, the simplicity of the language does not mean that the ideas are not complex or profound. Robyn describes the edgy change of energy when her Nan is not about thus: “When Nan goes out the air feels different on my skin, like shoes on the wrong feet.” She refers to the potency of silent bullying like this: “Being ignored has no words, nothing. Once words are involved there’s no going back.” When she takes the vanity case she expresses her ambivalence succinctly: “she won’t believe me because I don’t believe myself.”

Deborah Morgan’s husband supported wholeheartedly her decision to become a writer: “John is so proud of me. He always knew I was a restless soul and needed my freedom. I was a better wife because he let me loose; he trusted my pursuits: dressmaking, accountancy, teaching, writing. ‘Go for it,’ he said.” By taking a considerable cut in salary, retaining a part-time teaching role but restricting the tedious and time-consuming administrative aspects, she has combined her two passions: the desire to write and the desire to empower other people to write** by using her own experience as the model. “I want to give something back,” she explained. I asked her where this feeling of indebtedness came from. “I think of it as something I’ve never been able to do before. I suppose I never thought I had anything to give. Now I find I have a talent for something and the best bit of it comes from giving. That’s what we do when we write. Give a little bit of ourselves away, I think. I really like this Horace Mann quote: ‘Doing nothing for others is the undoing of ourselves’. So I suppose helping others is a way of helping ourselves out of helplessness.”

As a survival resource, Debbie’s ability to entertain people, to make them laugh, had been invaluable because it was a strategy that made her a welcome guest and it was also a way to pay something back. Like her character Robyn, Debbie’s interest in reading, in the power of storytelling, was first kindled at school. “I was the class clown. I used performance to hide behind. My greatest defence was making people laugh. I get a huge buzz from it, the sound of laughter. Especially making somebody cry-laugh. That’s the sign of real talent. Billy Connolly does it for me. I love the man and his work so much.” Like Robyn, Debbie read Anne of Green Gables to her Nan whose truncated education left her semi-literate.

I

asked Debbie about her literary icons: “Dickens, and Blake, in his

Songs of Innocence and Experience, I feel

are courageous in that they had vision enough to give voice to the most

vulnerable members of society. Dickens moved me deeply with the story

of Pip in Great Expectations. I was on a trip

with the school, to the Philharmonic Hall, I must have been eleven, and

by the end of the film I was in tears, as were many of the other kids.

It takes a skilled author to move an audience in that way, to get an emotional

response. That story still hangs around inside my mind. In many of Dickens’s

stories, his use of juxtaposition, in terms of corruption and innocence

is fascinating - and the twists and turns that he employs to highlight

the injustice of it. And not forgetting Toni Morrison, her work is amazing;

she’s not afraid to write about the unspeakable. All of this is

what interests me as a writer.”

I

asked Debbie about her literary icons: “Dickens, and Blake, in his

Songs of Innocence and Experience, I feel

are courageous in that they had vision enough to give voice to the most

vulnerable members of society. Dickens moved me deeply with the story

of Pip in Great Expectations. I was on a trip

with the school, to the Philharmonic Hall, I must have been eleven, and

by the end of the film I was in tears, as were many of the other kids.

It takes a skilled author to move an audience in that way, to get an emotional

response. That story still hangs around inside my mind. In many of Dickens’s

stories, his use of juxtaposition, in terms of corruption and innocence

is fascinating - and the twists and turns that he employs to highlight

the injustice of it. And not forgetting Toni Morrison, her work is amazing;

she’s not afraid to write about the unspeakable. All of this is

what interests me as a writer.”

It is easy to discern a Dickensian influence in the telling details of Debbie Morgan’s prose style and in the observations of economic and emotional survival at quite a basic level. Kids bring in a few opportunistic pennies shifting rubbish; Robyn’s parents tutor her, Fagin-style, in thieving. There are echoes of Bill and Nancy in her parents’ relationship. Mrs Naylor is a predatory mischief-maker; there are elements of sadism within the discipline systems at the school - what a horrid man Mr Thorpe the biscuit bully is! But like in Dickens, the negatives are counterbalanced by positives: there are wholesome relationships; there are good mothers; there is friendship. Debbie related anecdotes evoking spontaneous good times that contained a grotesquely humorous element:

“My friend’s mum sat on the settee with her hair snatched back in a ponytail smoking her fags. Saturday night, she’d transform herself into Liz Taylor, with a black wig, high heels, pencilled on eyebrows and ruby lips. She looked amazing. But when she came home drunk, the wig got lashed on the floor, the high heels were kicked off, Hank Williams played Honky Tonk in the kitchen and we’d eat plain omelettes, sing and dance until the birds started singing. We had so much fun.”

In terms of its treatment of the importance of the story-teller, Debbie’s novel is self-referential. It stands up as a consummate page-turner of a story according to all the reviews on Amazon and you only have to experience the tension and the nightmare horror of the denouement of Disappearing Home to be convinced. And it is horror, not melodrama, because we care what happens to Robyn and we also have some compassion for her mother. At the same time, one of its main themes is the almost poignant need human beings have for stories. Nan urges Robyn to read more of Anne of Green Gables so that she can tell her what happens - until they hit on a better way. Nan can main-line into the story if Robyn reads it to her directly. It’s the difference between the reported event and the actual event; the directness of the experience: a crucial point, reinforced by the filmic detail of Debbie Morgan’s writing. And there is another aspect of the storyteller-listener scenario: it is interactive; issues can be discussed, outcomes speculated upon; the storyteller has the power to play around with the story.

Disappearing Home has had a good reception, both as a story and as a piece of social documentation - of interest to anyone dealing with fragile families, or anyone who has experienced domestic violence. This first novel leaves plenty of scope for development and Debbie is writing a sequel: “Robyn is sixteen, experiencing various things for the first time - first job, first alcoholic drink…and I’ve included more humour in this one.” In addition, she is writing a novel about a social worker with child-care issues in which her husband has agreed to look after their baby then changes his mind.

Debbie has also written an unpublished book of poetry: Making a Suit for Elvis.

Debbie has said, and other people have told her, that Disappearing Home is an important book and she passionately wants to get it out there to the people who will benefit from reading it. “But I need help in promoting it,” she admitted.

And whilst you are talking to Deborah Morgan you can see the communicative passion in her face as she answers questions without needing to be asked and you can feel the stories bulging out of her, jostling one another to get heard; staring at her like the gawping kid at the end of Disappearing Home. They won’t budge till she’s told them.

She won’t budge till she’s told them.

*Disappearing Home (Tindal Street Press, 2012) was reviewed for Nerve magazine by Sandra Gibson, November 2012 - read the review here

** Debbie teaches at Blackburne House which, amongst other facilities, provides education for local women, including hard to reach and disadvantaged students.