| HOME |

| NERVE |

| REVIEWS |

| ARCHIVE |

| EVENTS |

| LINKS |

| ABOUT US |

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| BACK ISSUES |

| CONTACT US |

6/12/2007

Interview

with Alun Parry

Interview

with Alun Parry

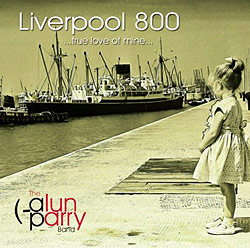

Alun Parry is acknowledged as one of Liverpool’s leading acoustic based performers and songwriters. His albums Corridors of Stone and Liverpool 800 and his work to promote live music have received widespread critical acclaim. In this abridged version of a recent interview Parry speaks about the values that underpin his work.

‘True Love of Mine.’

The title song on your latest album is a passionate

love song to the city. What does it mean to love Liverpool?

My association with Liverpool was doubly assured: I was born here and

named after a Liverpool centre-forward called Alun Evans. It feels like

home; I can only go on holiday for four days and I want to be tethered

back to here. Things don’t feel atomised here – there’s

a village feel about it. It’s simple – it feels like a good

place to be and I like the sense of solidarity. Liverpool people have

long been associated with this – we help one another out; we stick

together; we’re politically bloody-minded. In the Thatcherite mid

Eighties - a time of economic disaster for the city - Liverpool and Everton

were playing in the F.A. Cup Final at Wembley. But it was the call of

‘Merseyside’ that went round the stadium. Any partisan feelings

about individual teams were subsumed in the defiant roar of being from

Liverpool. I remember this ambassadorial imperative from a very early

age. Family holidays were taken in Blackpool. ‘Behave. You’re

not in Liverpool but you’re from Liverpool,’ my mother would

say. I’m proud of Liverpool because my heart and the heart of the

city seem to beat to the same rhythm. I have a strong value system and

a certain positivity in adversity, which I feel Liverpool broadly shares.

At the same time I would want to distance myself from ideas of superiority

or a sense of ‘nationalism’ about the city. The grotesqueness

of self superiority, coupled with the idea that birthplace and ‘heritage’

as the issue of overwhelming importance, is a credo I find revulsion for.

‘Read the buildings and you’ll see.’

With the recent opening of the new Liverpool

International Slavery Museum in the year that marks the 200th anniversary

of the abolition of slavery there has been a lot of publicity about this

part of Liverpool’s history and one of the songs on the new CD addresses

the issue. How do Liverpool people in general deal with this?

Eric Lynch, a black man in his seventies does tours of the waterfront.

I didn’t know 95% of what he told me about slavery. ‘Read

the building and you’ll see,’ he says. When you look at the

carvings glorifying the slave trade on the buildings in Liverpool and

Bristol you start to understand the economic mindset that perpetrated

this terrible trade. I am ashamed - but I don’t know if I’d

necessarily use that word for everyone else. I would say most people don’t

think about it too specifically. That’s why Eric’s tours and

the Slavery Museum are important: they keep the issue visible. Some people

want the ‘grotesque’ carvings of slaves manacled removed.

I don’t agree with this; people need to see these ideas.

‘For I see a world that is owned by the few.’

Some of your songs have a strong political

content, dealing as they do with the work conditions of ordinary working

people [My Granddad was a Docker] and more contemporary issues of immigration

and asylum seeking [I Want Rosa to Stay]. To what extent do you walk your

talk?

I would call myself extra-parliamentary. I believe the biggest power we

have is social power. Changing things is a ponderous parliamentary process;

there are simpler, more direct means. When the issue of BNP flyers being

delivered with the post arose there was a call to change the law but all

that was needed was for the postal workers to refuse to deliver them.

I believe in the power of ordinary people to affect change. I don’t

believe this in a romantic sense; I ‘m speaking practicalities.

This belief is a recurring theme in my work, my music, my politics, and

my approach to DIY music. There’s a long history of working class

toil in Liverpool and the song about my granddad celebrates that. People

like him built the city just as surely as anybody else did.

I don’t just sing about political issues. The Labour government

began imprisoning asylum seekers in my local prison: HMP Walton. I founded,

with some colleagues, an action group called Merseyside Against Detention

which campaigned against this: holding several demos at the prison; getting

a double page spread in the Liverpool Echo; and ensuring it was the front

page story in the Independent on Sunday. In addition, we went to the prison

regularly and campaigned on behalf of the detainees. This is some of the

background to my motivation for writing I Want Rosa to Stay. The song

celebrates those positive attributes that immigrants have to offer at

the same time that it challenges the dodgy economic arguments against

their presence and the cynical deflection of attention away from the inadequacies

of the status quo onto a scapegoat.

I’m always happy to play for free for any cause I broadly agree

with.

‘Don’t just sign the petition.’

I notice from your blogs and the article you

did for The Big Issue that you have a direct, concise, journalistic style.

I have some tenuous connection with political journalism in that I used

to work as a volunteer on Labournet, a site that arose as a result of

the dockers’ dispute that went on for nearly two years. We used

the net to disseminate information on a global scale: looking at media

coverage from a worker’s point of view. It was the sort of stuff

that doesn’t otherwise get an airing and it was immediate –

the photos and reports were all up there the same day. It was bottom-up

reporting - ordinary people telling their stories without relying on Murdoch

or the BBC.

‘The

listener decides.’

‘The

listener decides.’

It appears you have some radical views with

regard to the economics of the music business.

I’ve applied the busking philosophy to my present circumstances.

My albums are conventionally available in the shops with a price marked

on them but on my site I’m making my music freely available, just

as I did on Bold Street. There is still an option to put money into my

‘busker’s hat’ – the purchaser decides how much.

It’s revolutionary – it goes against the trend of trying to

sue kids for downloading music off the internet.

I’ve never understood why, if I’m bringing in a load of fans

to listen to my music and spend money over the bar I’m also expected

to pay a lot of money to hire a room that would otherwise be empty. I

don’t mind paying for a good P.A. and an in-house engineer; but

if I’m providing the P.A. and the engineer and doing the promotion

and booking the support bands and bringing in lots of trade for their

bars I don’t see why I should be charged. I hope to encourage a

self-reliant method of getting gigs, showing, for example, where musicians

can stage their own gigs without unfair room hire charges. I’m also

encouraging people to let me know which venues actually pay something

for the services of musicians even if it’s only a percentage of

the bar tab to keep it risk free for them.

My campaign to highlight music friendly venues has the support of Echo

music writer Jade Wright who is publicising it on her blog. Information

will be collated and there will be a free on-line directory of such venues.

You’ve talked about DIY music promotion.

How did you develop it?

You can’t get much more DIY than my musical origins - I wrote songs

as a kid then became a busker using my uncle’s classical guitar.

I like to have power over where I play; I look out for music friendly

venues; I like to negotiate the deals personally; I like to select the

support acts carefully. If I have this control I get a better deal and

the people I perform with benefit as well. My aim is to fill a room with

an audience (whom I don’t charge) and a stage with good musicians.

I also want to be performing my own music. I actually love being in a

band. The band is not a traditional ‘lets find our sound band.’

I have my sound from my days as a solo artist. I now want people to add

to that sound rather than create a new one so I write all the songs.

What’s happening now?

My latest venture is to try to set up a similar arrangement in other cities

and towns. I’ve taken Manchester, Preston, Liverpool, Birmingham,

Derby and Leeds and the idea is to do an acoustic night in each of these

once every two months at which my band would perform. In addition I would

search the internet for three acts local to the area I’m in. They

have to be acts I like; I’m a big believer in quality control so

I never just go on recommendations. I’m also very careful about

venues; I don’t want someone’s night out parking itself at

my event!

For the full version of this interview and more information about Alun

Parry please visit www.parrysongs.co.uk

Click here to read Sandra's review of Liverpool

800: True Love Of Mine